Some light quantum mechanics (with minutephysics)

Light Quantum Mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a huge topic, far more than what can be presented in a single lesson. The goal here is to present foundational intuitions through a specific example. What topic would set the right intuitions for someone before they dove into, say, the Feynman lectures? Well, a natural enough place to start, where quantum mechanics itself started, is light. Specifically, if you want to learn quantum, you have to understand waves and how they’re described mathematically. This leads to the conclusion of relating the energy in a purely classical wave to the probabilities that govern quantum behavior.

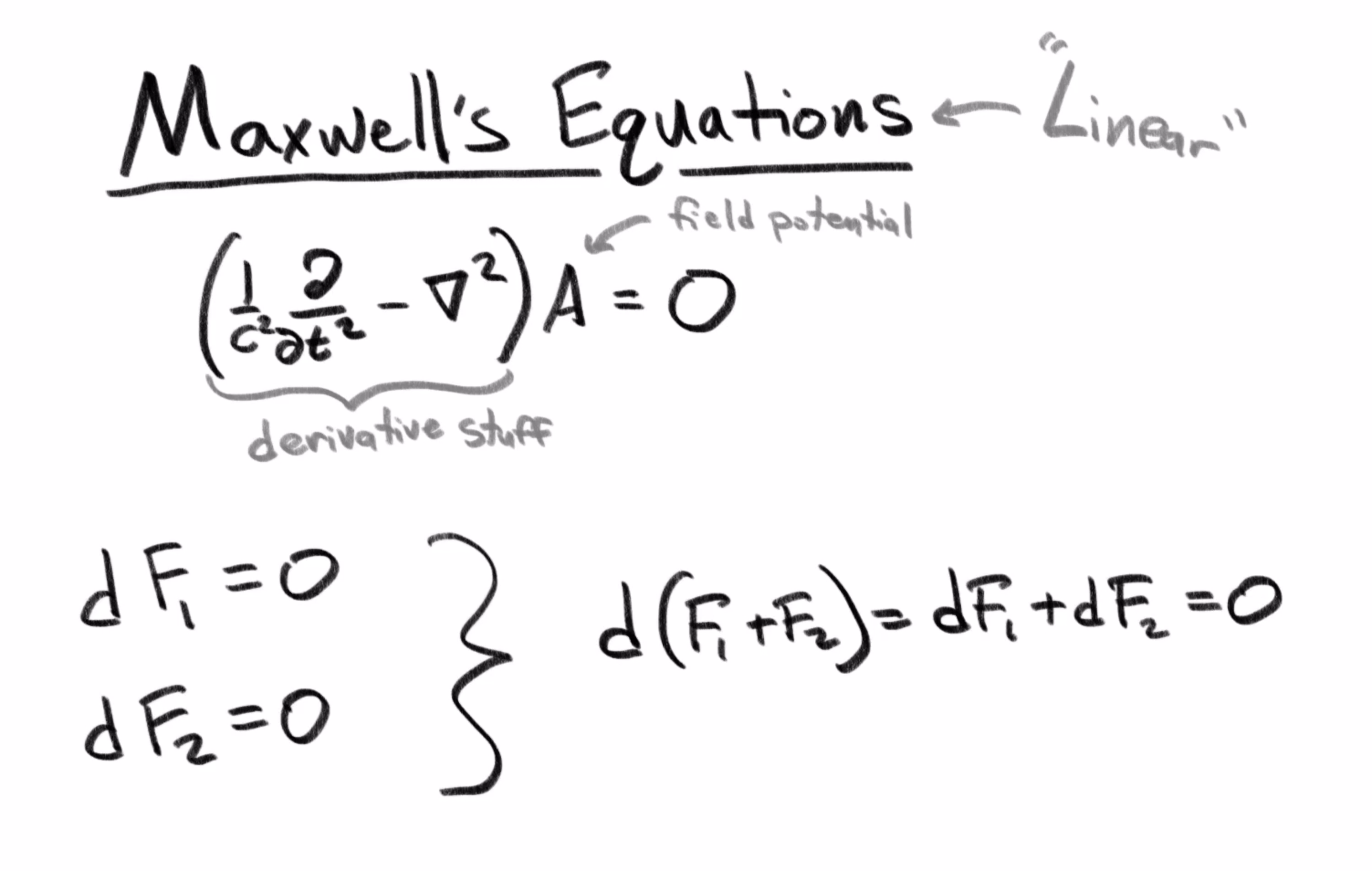

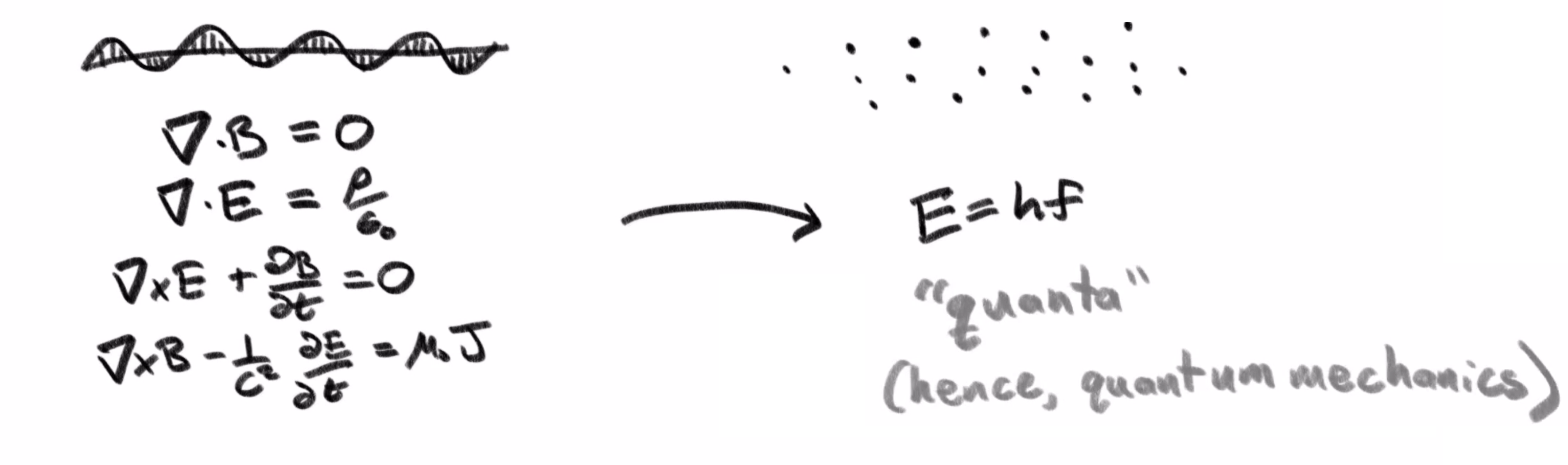

Maxwell's Equations

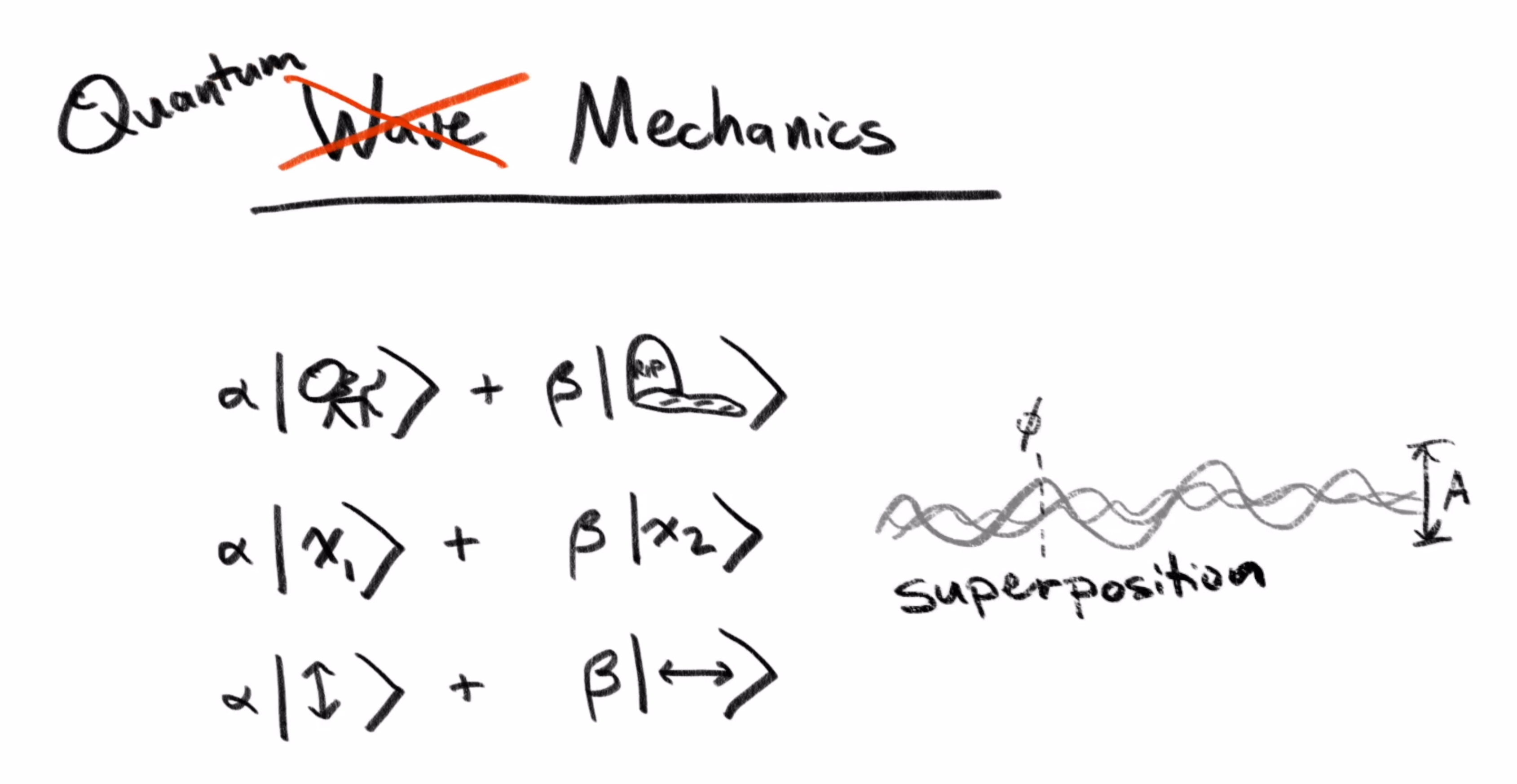

Let’s learn some light quantum mechanics through the quantum mechanics of light. In fact, we’ll actually spend most of the time talking through the pre-quantum understanding of light, since that sets up the relevant wave mechanics. The thing is, a lot of ideas from quantum mechanics, like describing states as superpositions with various amplitudes and phases, come up in the context of classical waves in a way that doesn’t involve any of the quantum weirdness people might be familiar with. This also helps to appreciate what’s actually different in quantum mechanics, namely certain restrictions on how much energy these waves can have and how they behave when measured.

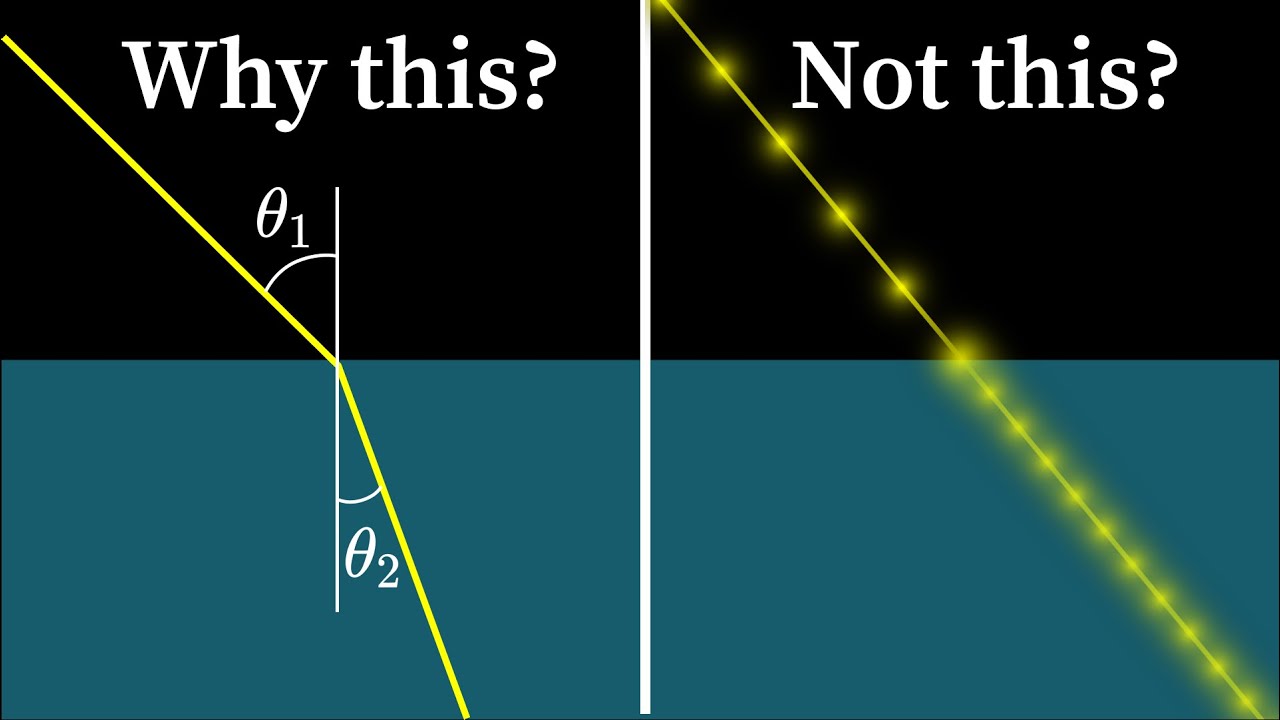

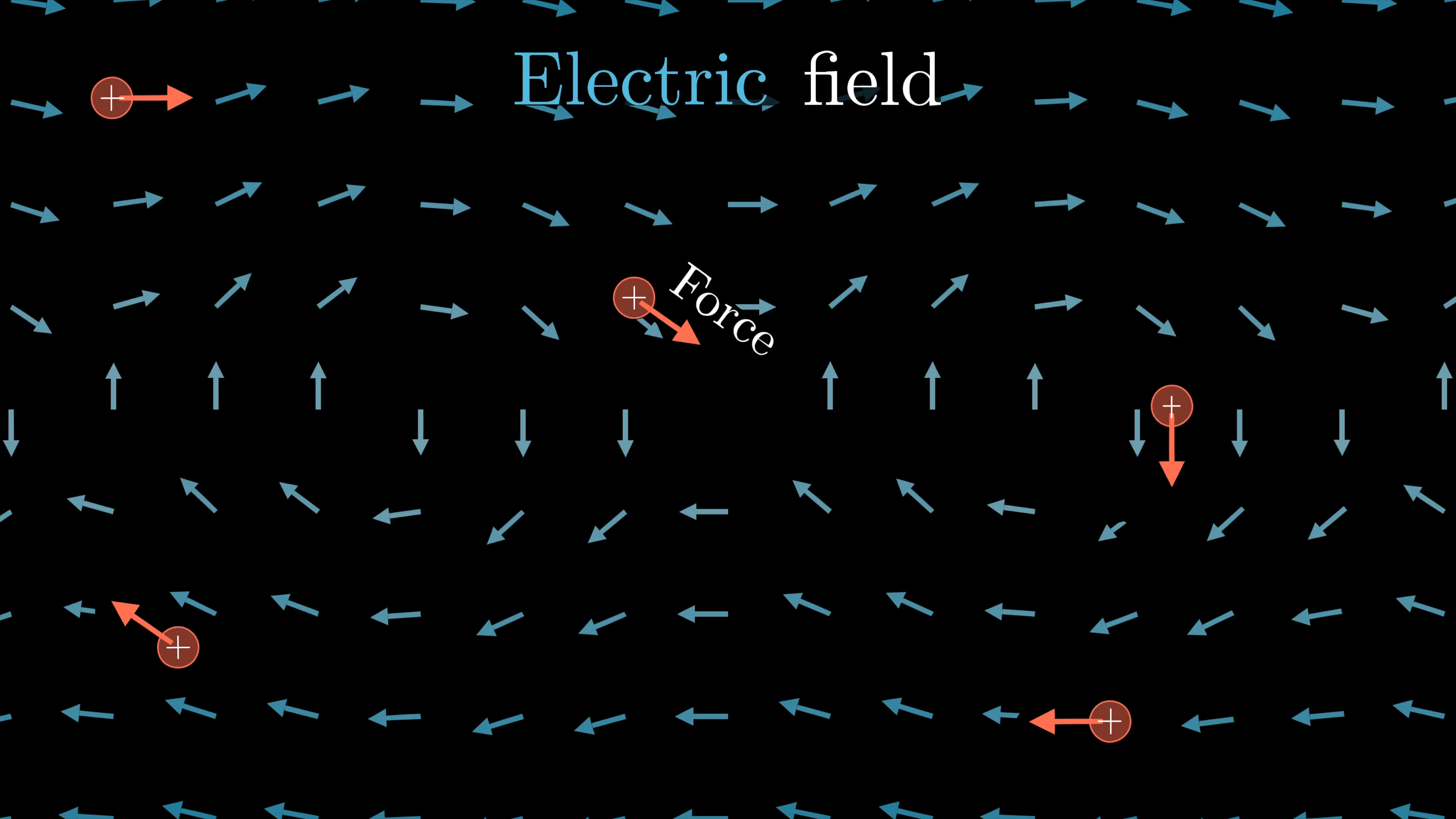

In the late 1800’s, light was understood to be a wave in the electromagnetic field. Let’s break that down. The electric field is a vector field. That means every point in space has some arrow attached to it indicating the direction and strength of the field.

Each particle will accelerate in the direction of the nearby arrow.

The physical meaning of those arrows is that if you have a charged particle in space, there will be a force on that particle in the direction of the arrow. The magnitude of the force is proportional to the length of the arrow and the specific charge of the particle.

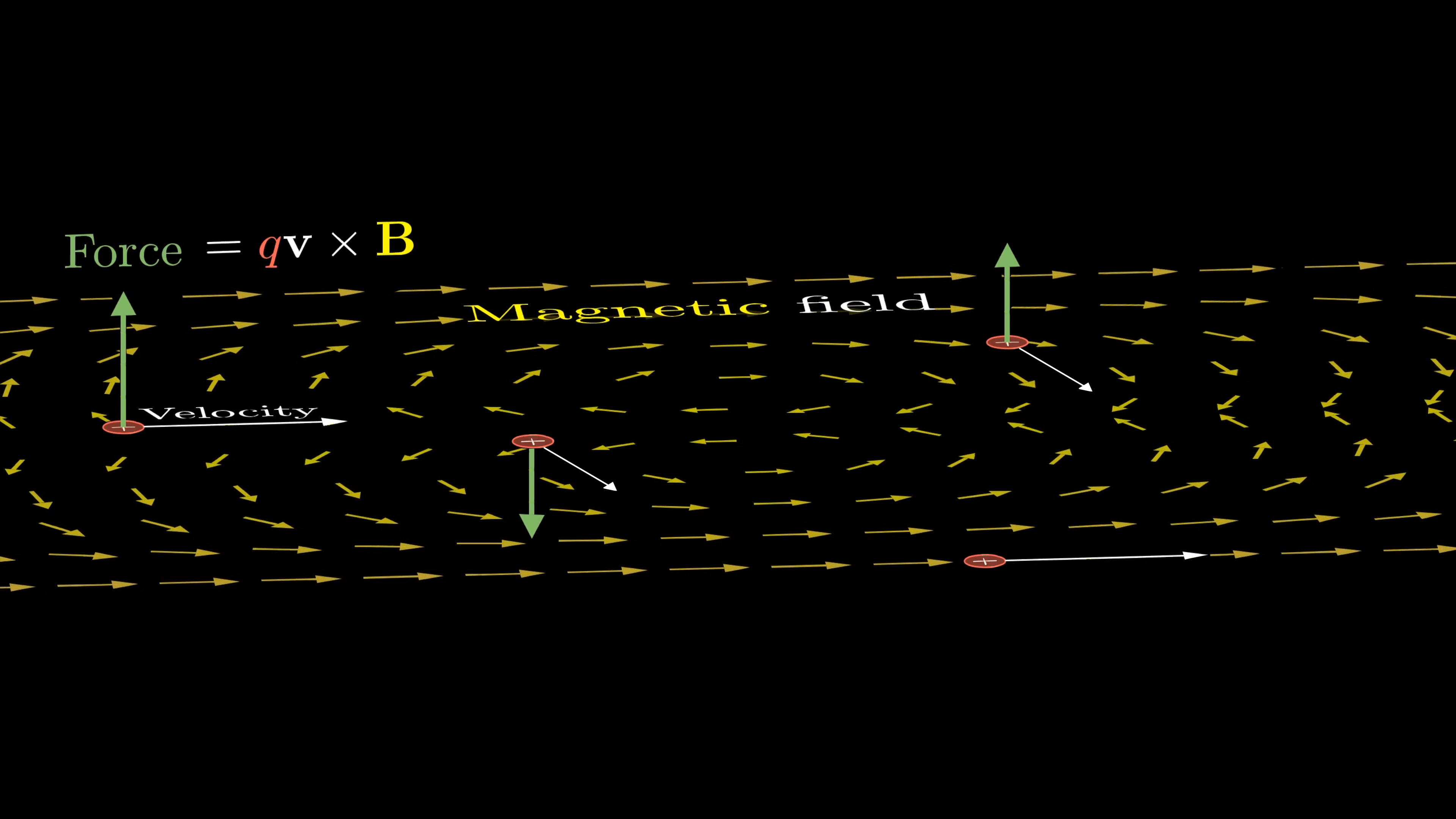

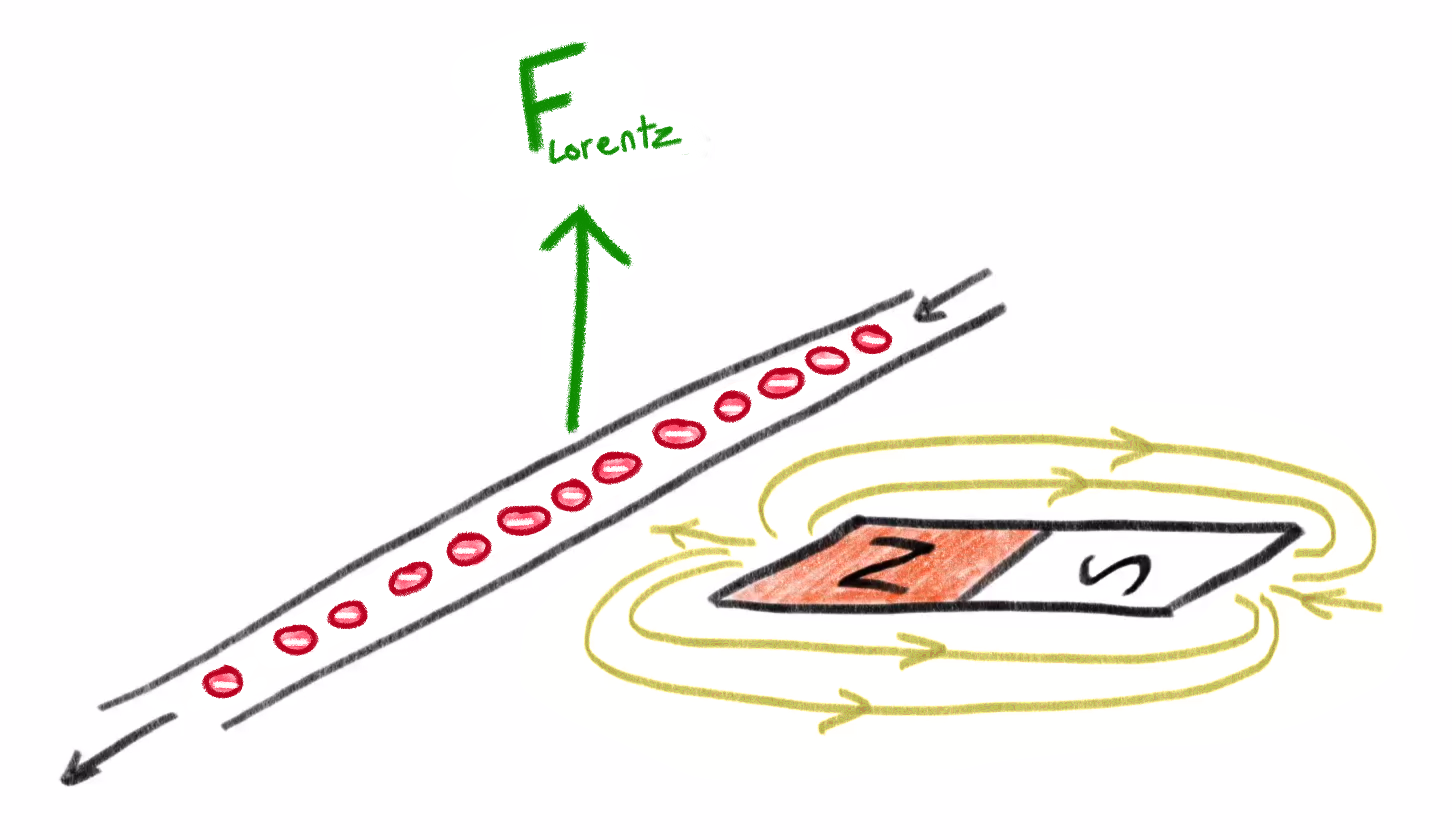

Likewise, the magnetic field is also a vector field. Now the physical meaning of each arrow is that when a charged particle is moving through space, there is a force orthogonal to both its direction of motion and to the direction of the magnetic field. The strength of that force is proportional to the charge of the particle, its velocity, and the length of that arrow.

Each particle will accelerate in a direction perpendicular to both the velocity and direction of the field at the particle’s position. The direction can be found using the right hand rule.

For example, a wire with a current of moving charges next to a magnet is either pushed or pulled by that magnetic field.

These particles produce a force opposite of the right hand rule because they are negatively charged.

In the illustration above, the charged particles moving through the wire produce a force that is orthogonal to their direction of motion and the direction of the magnetic field. So imagine, what happens if the direction of the charged particles changes?

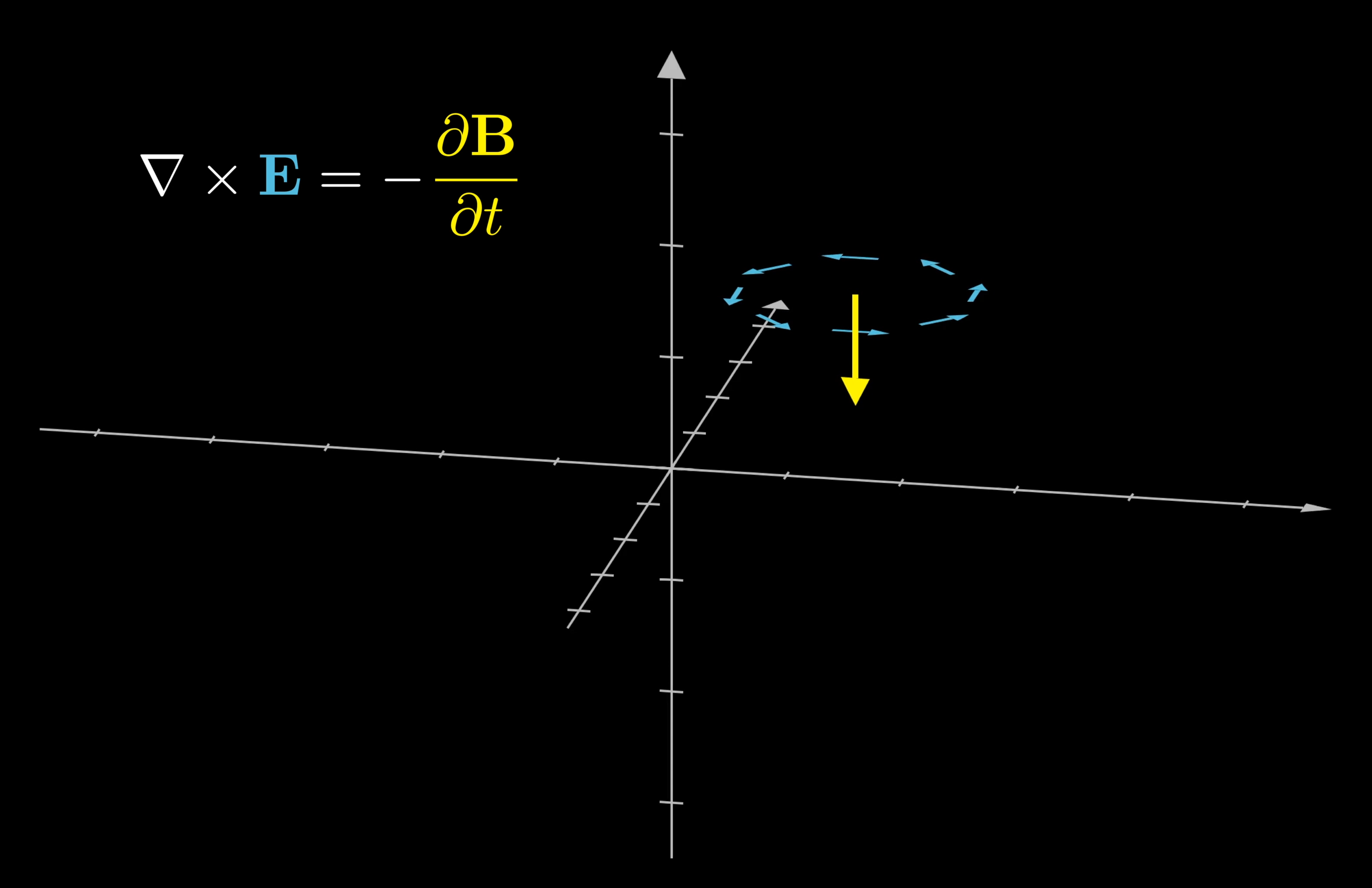

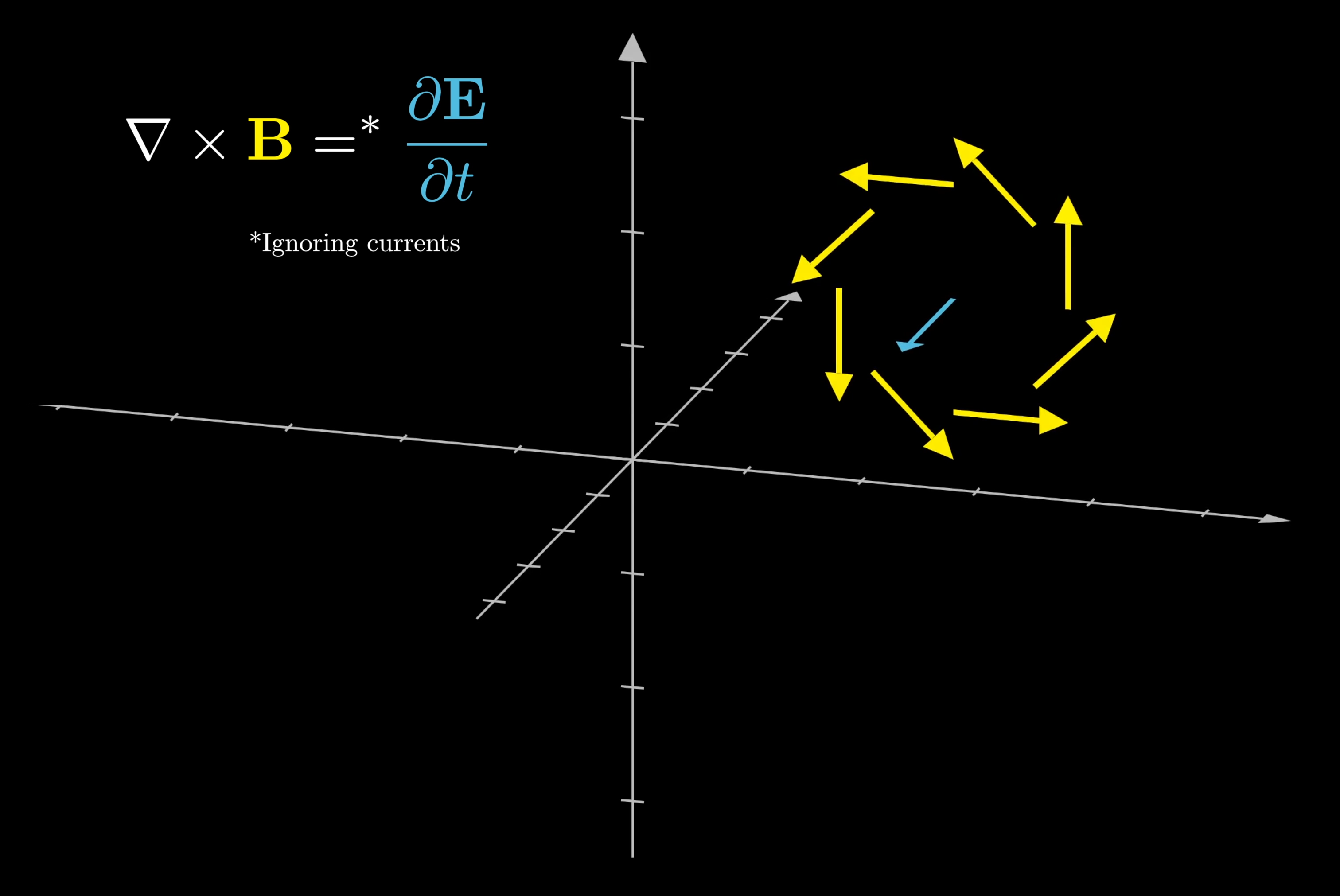

The direction of the force flips 180 degrees and will point downward instead.A breakthrough in 19th century physics of understanding how these two fields work are Maxwell’s equations, which among other things describe how each of these fields can cause a change to the other. Specifically, Maxwell’s equations tell us when the electric field arrows seem to be forming a loop around some region, the equations dictate that the magnetic field will be increasing in that region, orthogonal to the plane of the loop.

Symmetrically, such a loop in the magnetic field causes a change to the electric field within it.

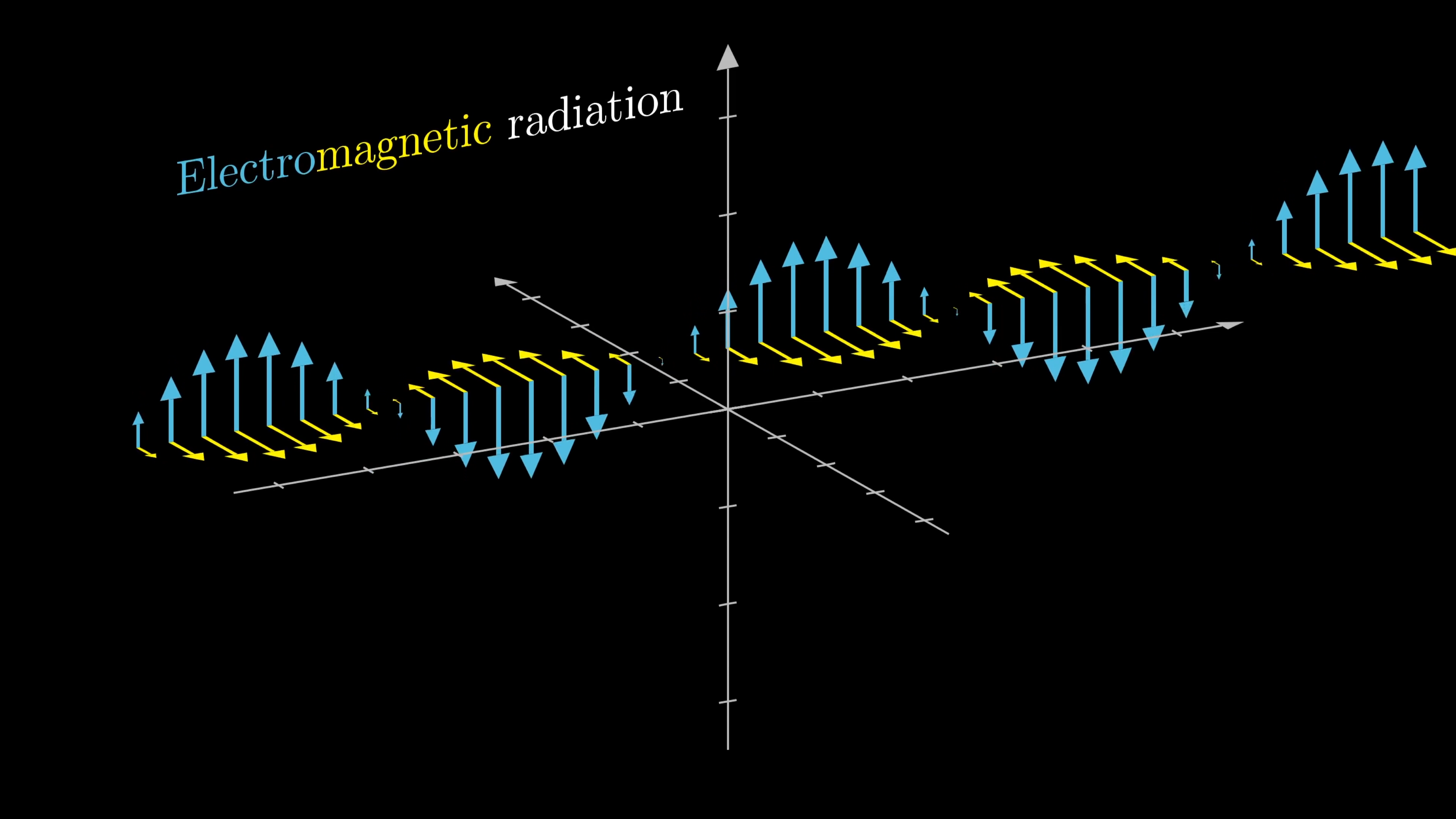

The specifics for how exactly these equations work are really beautiful, and worth checking out their own video. For now, all you need to know is that one natural consequence of this mutual interplay in how changes to one field cause changes to the other is that you get these propagating waves where the electric and magnetic fields are oscillating, perpendicular to each other, and perpendicular to the direction of propagation. When you hear the term “electromagnetic radiation,” which refers to things like radio waves and visible light, it is fundamentally a propagating wave in the electric and magnetic fields.

If you isolate a point in the electromagnetic field that the radiation passes through, the vectors attached to the point representing the electric and magnetic components of the field oscillate with respect to time and form the wave shape shown below.

Of course, it’s now almost mainstream to know of light as “electromagnetic radiation,” but it’s neat to think about just how surprising this must have been in Maxwell’s time. That these fields which have to do with forces on charged particles not only have something to do with light, but that light is defined as a propagating wave in these two dancing fields. The fields are tied together in this mutual oscillation of increasing and decreasing magnitude.

Describing Waves

Let’s take a moment to lay down the math used to describe waves. It’ll still be purely classical, but ideas that are core to quantum mechanics, like superposition, amplitudes and phases come up in this context. Arguably, there is a clearer motivation for what they actually mean.

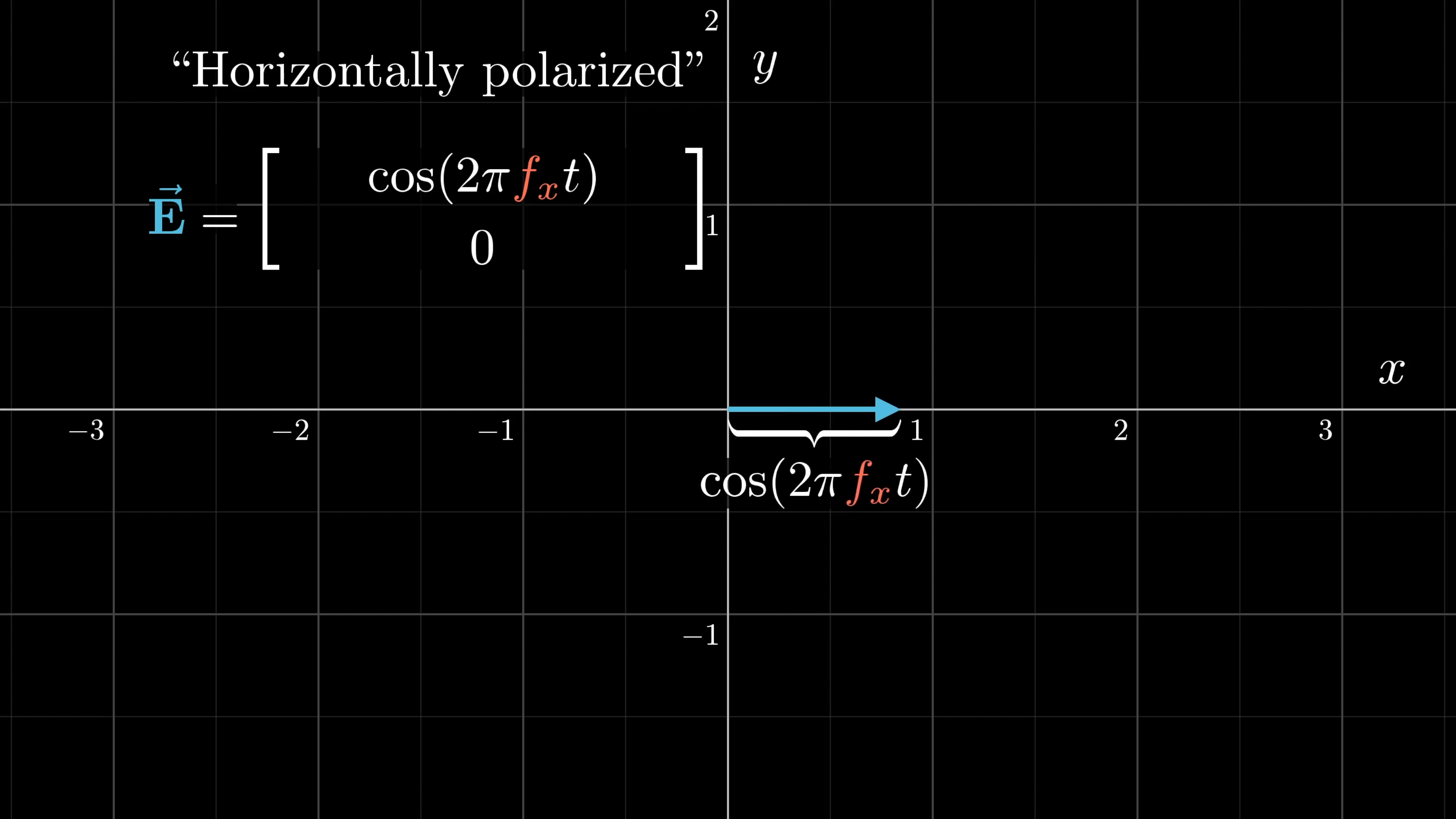

Think of the electromagnetic wave as directed straight out of the screen towards your face. Let’s go ahead and ignore the magnetic field, just looking at how the electric field oscillates. Also, we’ll focus only on the oscillating vector on the plane of the screen, which we’ll think of as the -plane.

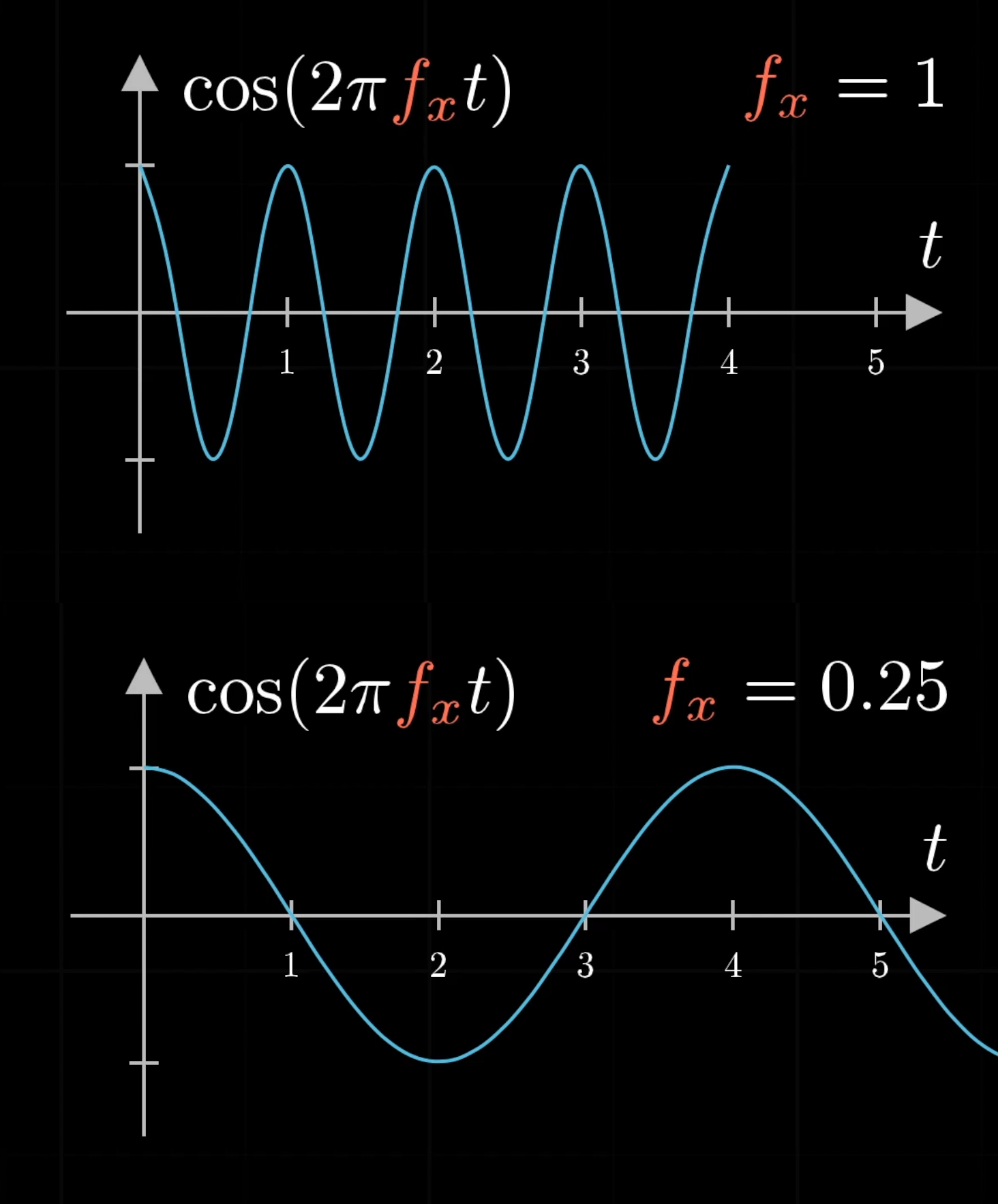

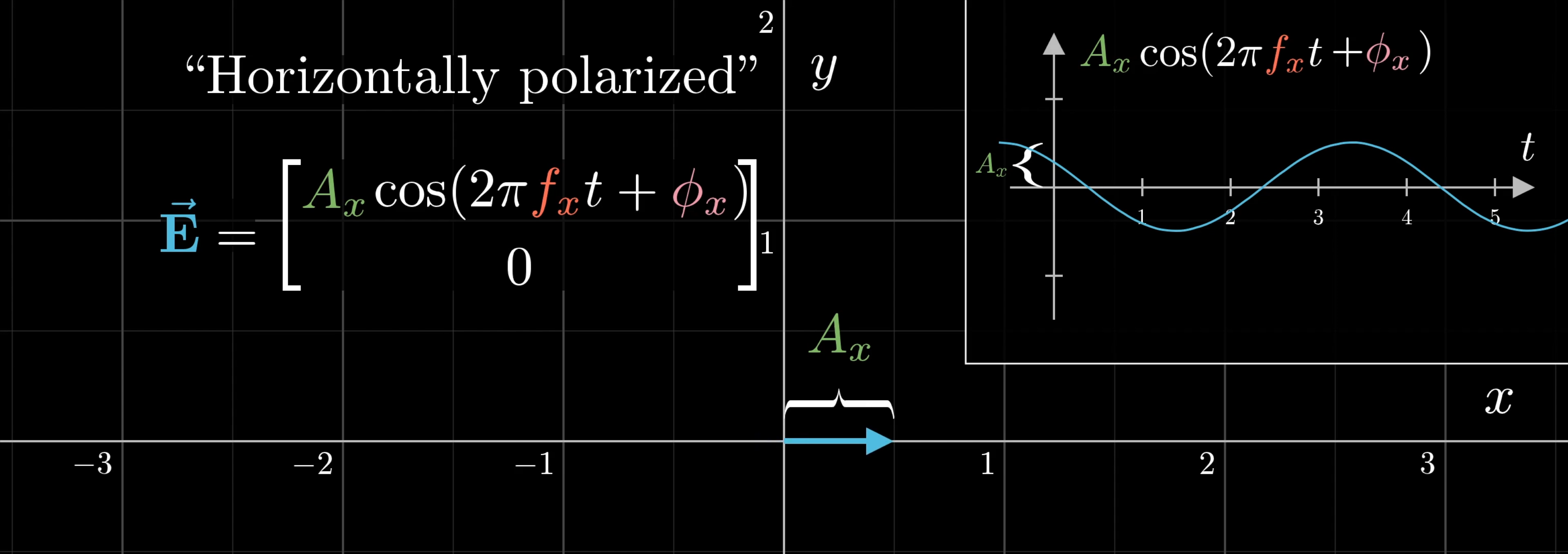

If it oscillates horizontally like this, we say the light is horizontally polarized. So the -component of this electric field is at all times, and we might write the -component as , where this represents some frequency, and is time. So if is , it takes exactly second for this cosine function to go through a full cycle. For a lower frequency, it takes more time to complete a cycle.

Electromagnetic radiation is divided into many categories, some of them are: radio, infrared, visible light, X-ray, and gamma. Which one takes the shortest amount of time to complete a cycle?

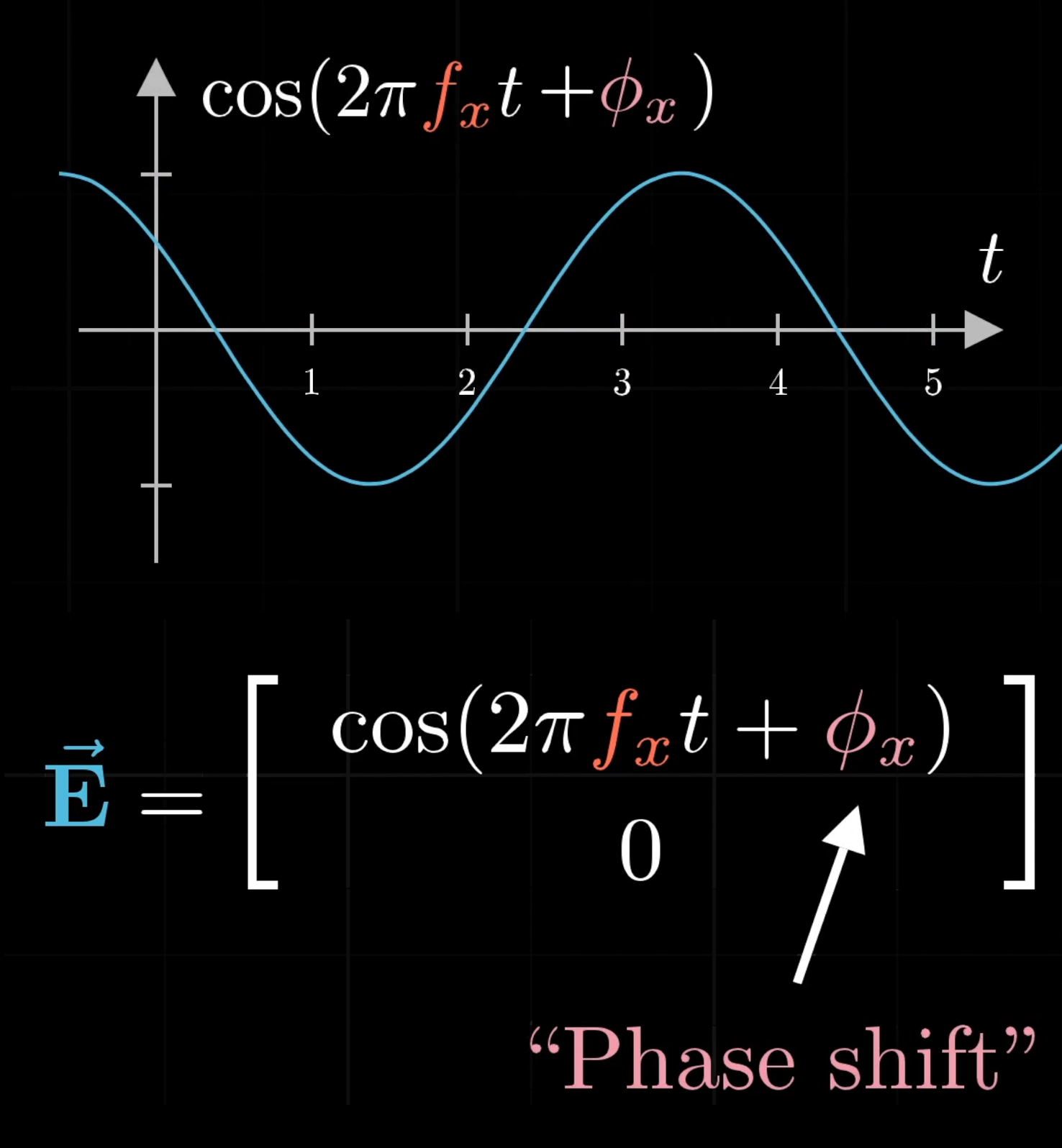

We’ll include another term in our wave equation, , called the “phase shift.” It tells us where that vector is at time . You’ll see why that’s important later on.

By default, cosine only oscillates between the values of and , so let’s put another term in the front here to give us the amplitude of the wave.

The amplitude, frequency, and phase define a wave. Try experimenting with different combinations to see how each component impacts the shape of the wave:

What value of would turn the cosine function into the sine function?

Classical Wave Mechanics

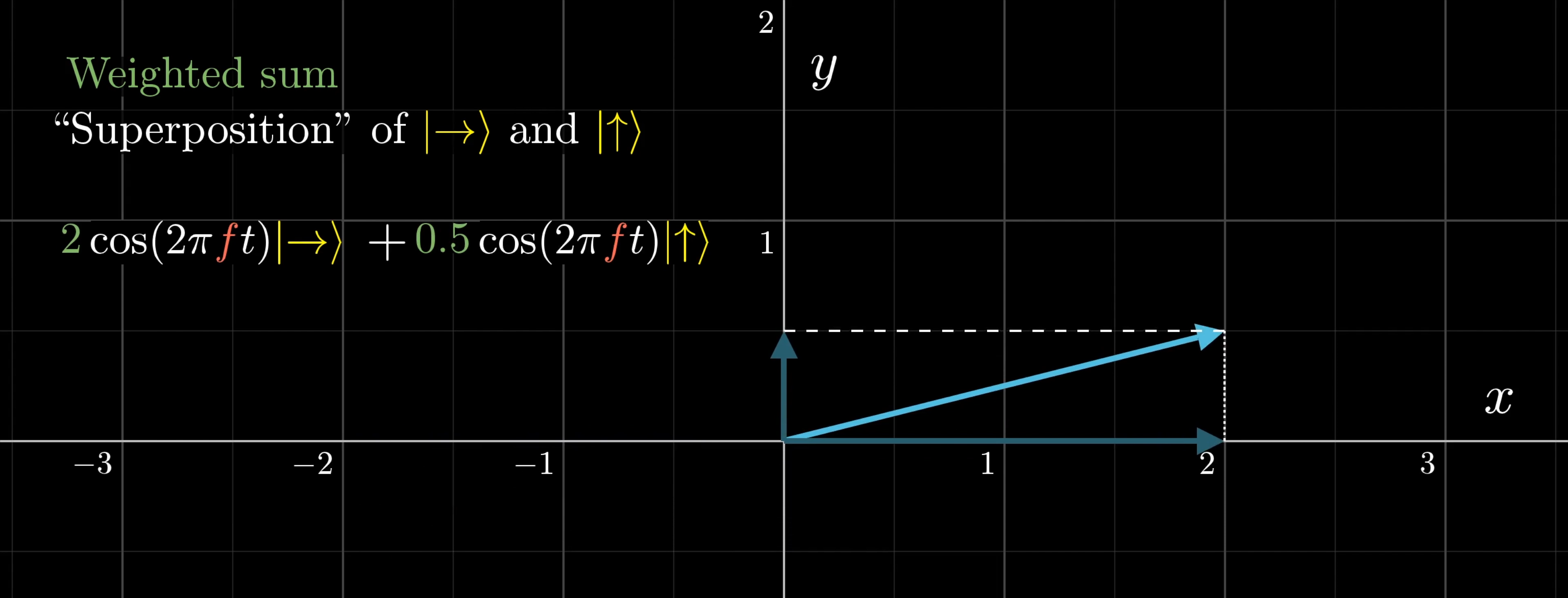

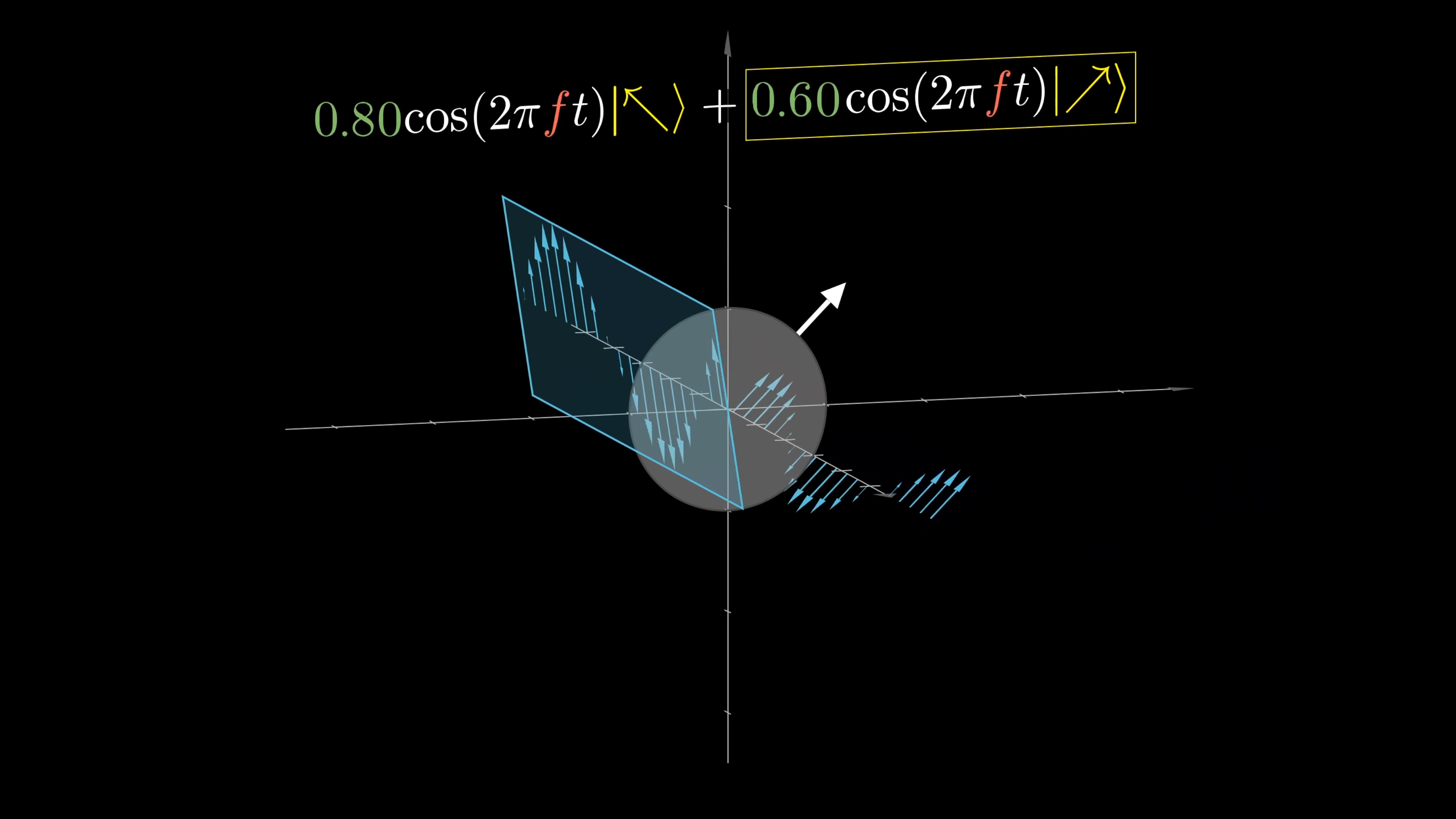

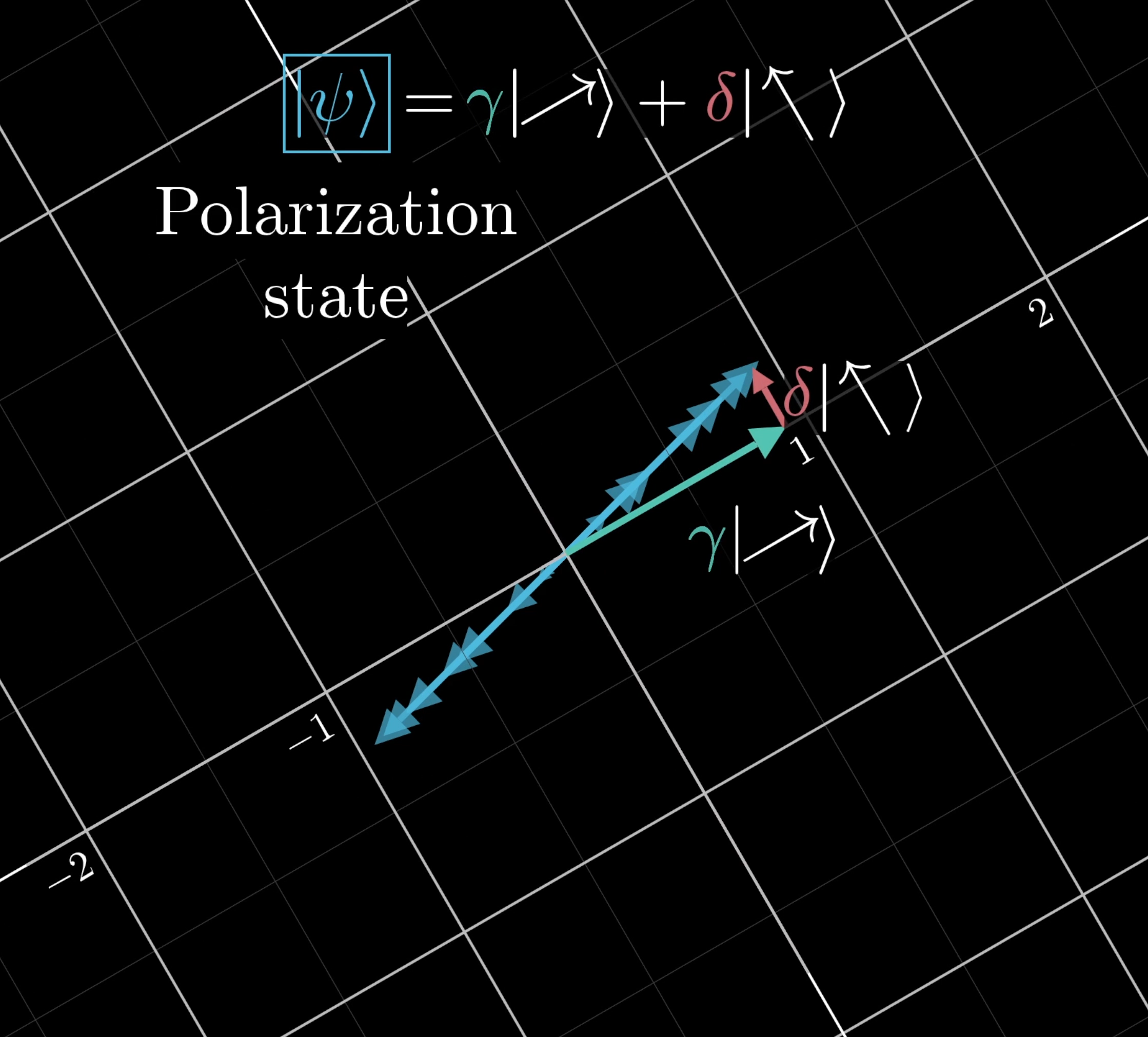

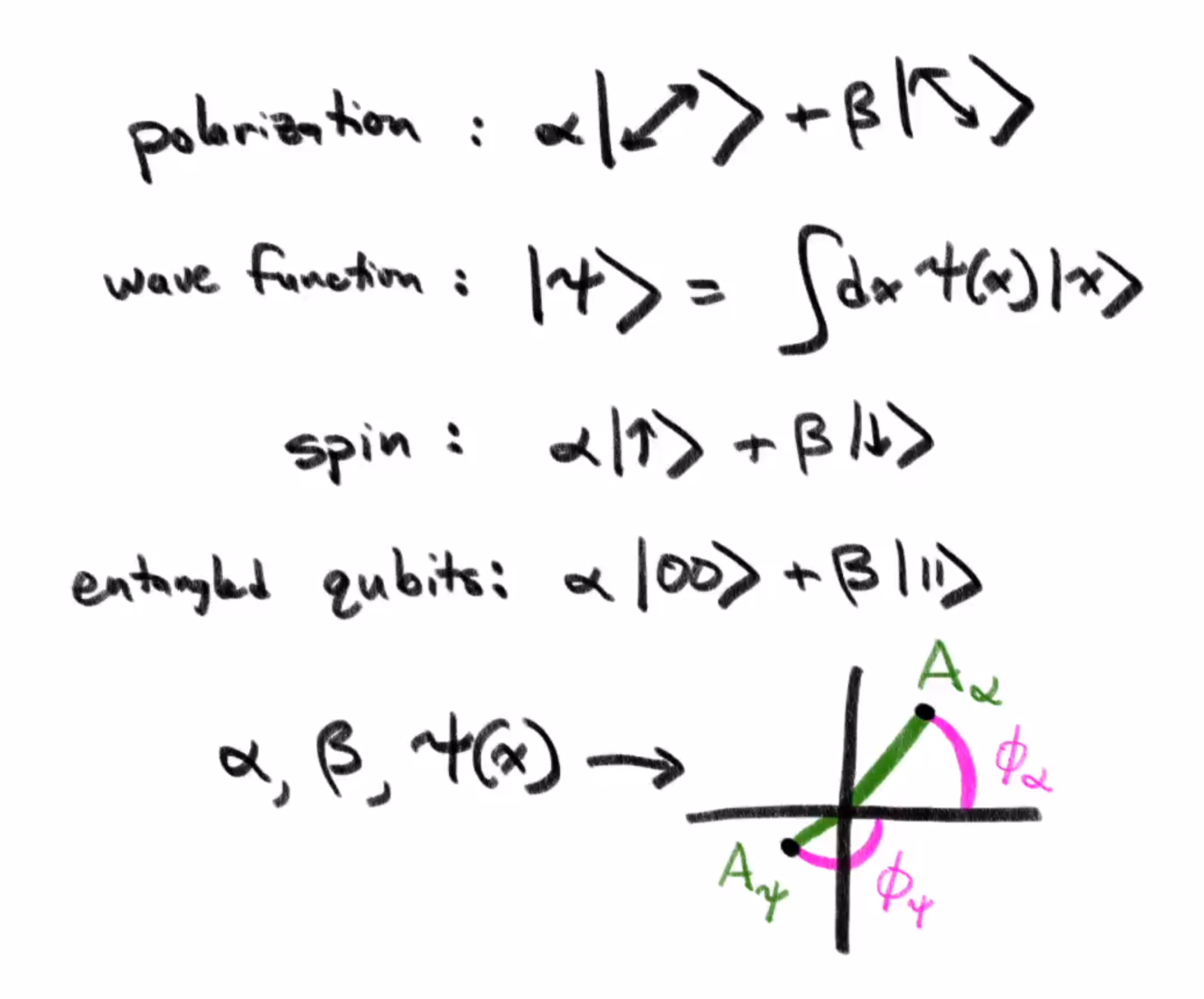

To make things look a little more like they often do in quantum mechanics, instead of writing as a column vector, we’ll separate the two components using these symbols, called “kets.”

These kets come from Dirac notation where the ket indicates a unit vector in the horizontal direction and the ket indicates a unit vector in the vertical direction.

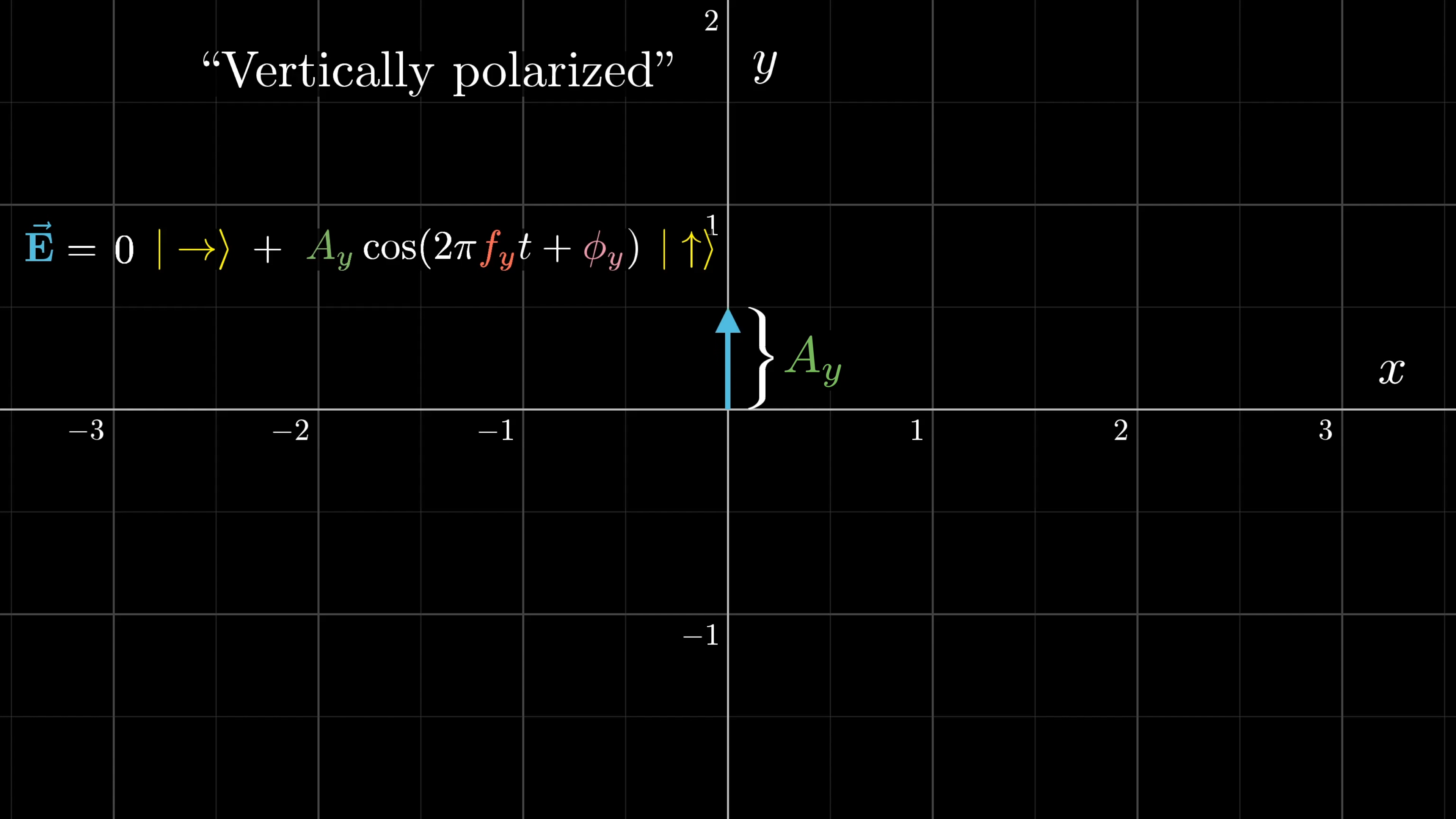

If the light is vertically polarized, meaning the electric field is wiggling purely in the up and down direction, the horizontal component will be and the vertical component is a cosine with some frequency, amplitude and phase shift.

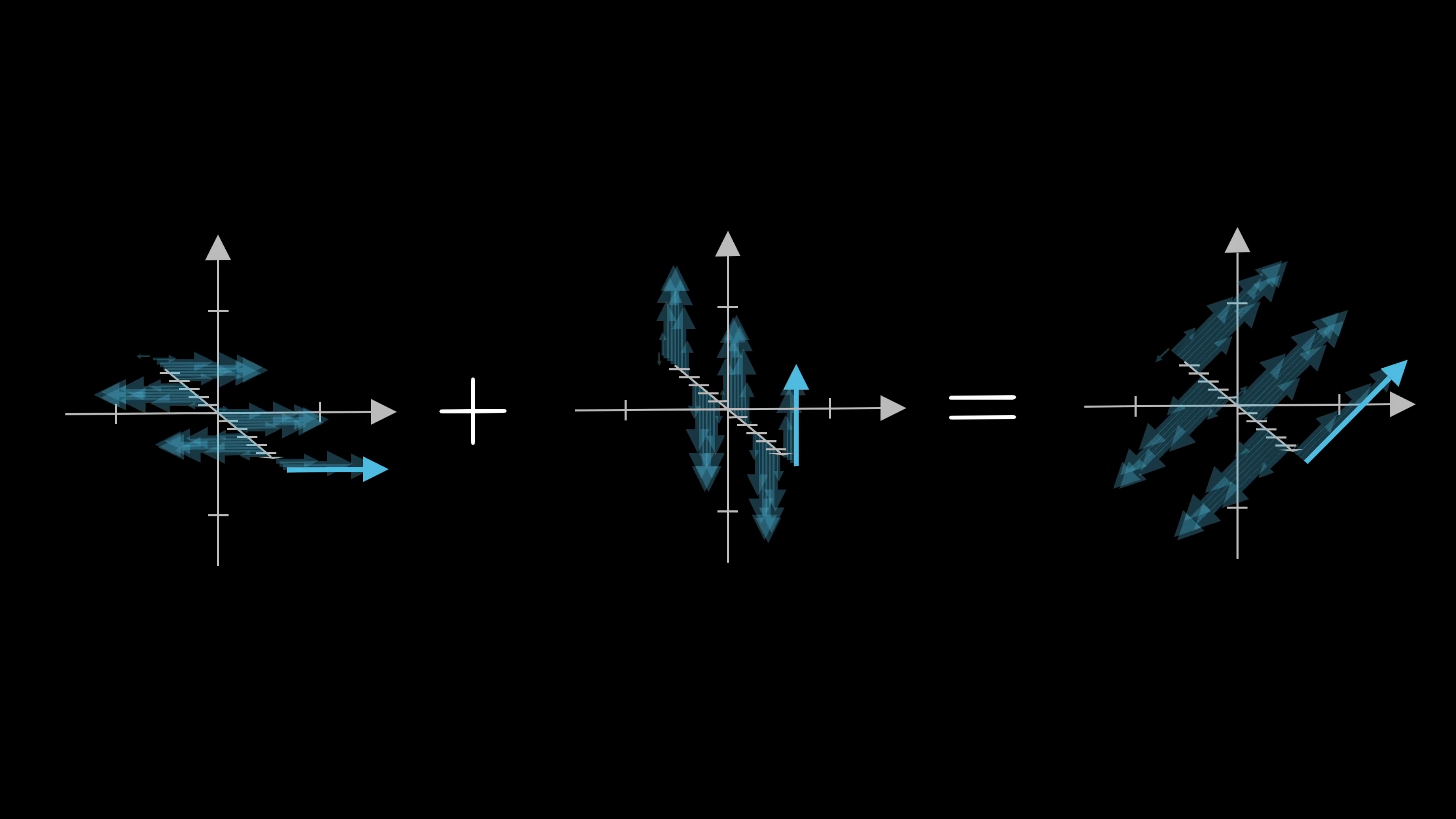

If you have two distinct waves; two ways of wiggling through space over time that solve Maxwell’s equations, then adding both of these together gives another valid wave, at least in a vacuum.

That is, at each point in time, add these two vectors tip to tail to get a new vector. Doing that at all points in space, and all points in time, gives a new valid solution to Maxwell’s equations.

This is because Maxwell’s equations in a vacuum are what’s called “linear” equations. They’re essentially a combination of derivatives acting on the electric and magnetic fields to give zero. If one field satisfies this equation , and another field satisfies it , then their sum, , also satisfies it, since derivatives distribute. So the sum of two (or more) solutions is also a solution.

The derivative operator is linear, so it can be distributed to the fields.

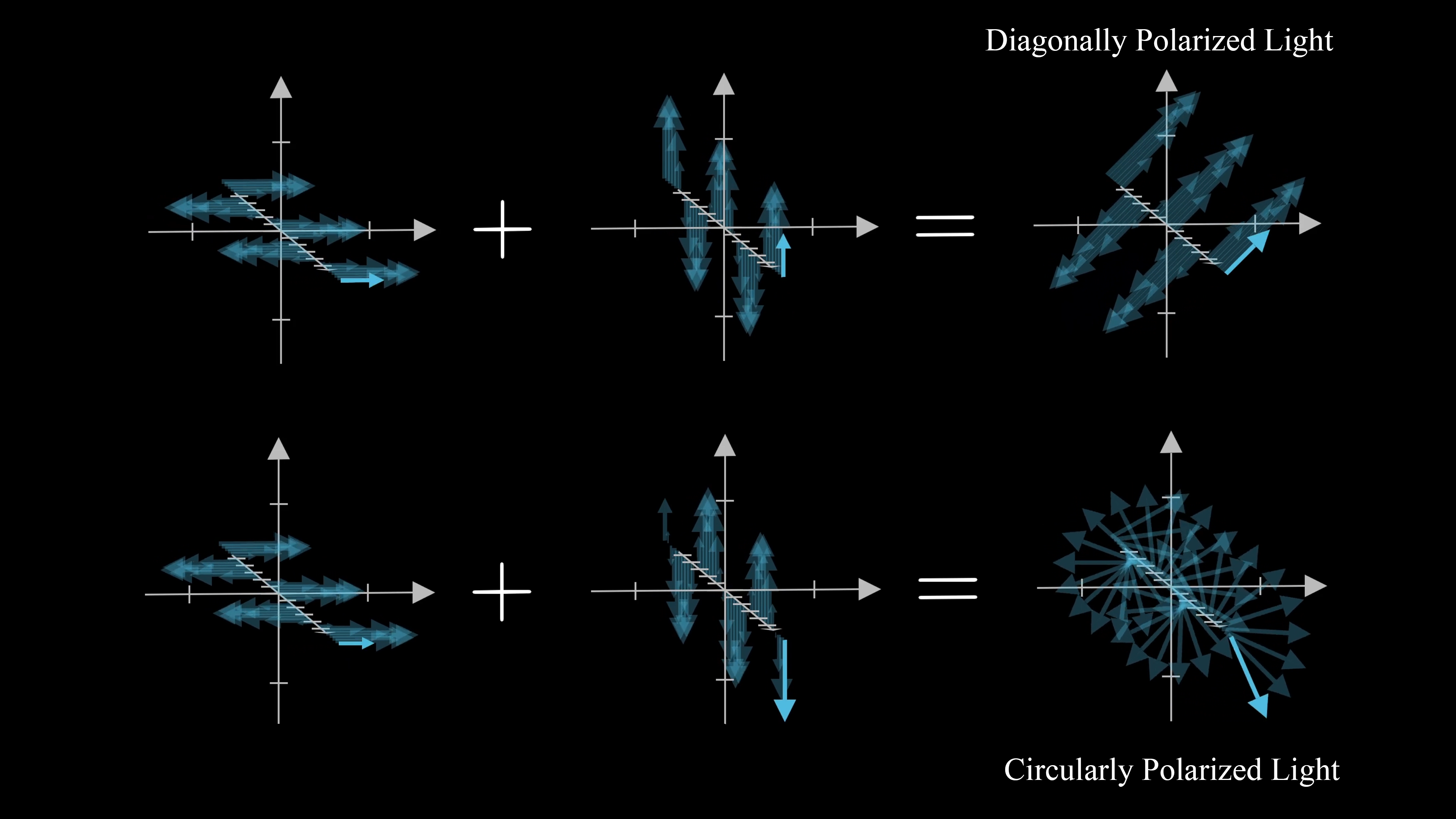

The new wave is called a “superposition” of the first two. Superposition essentially means “sum,” or in some contexts, a “weighted sum,” since if you include some kind of amplitude or phase shift to each of these components, it can still be called a superposition of the two original vectors.

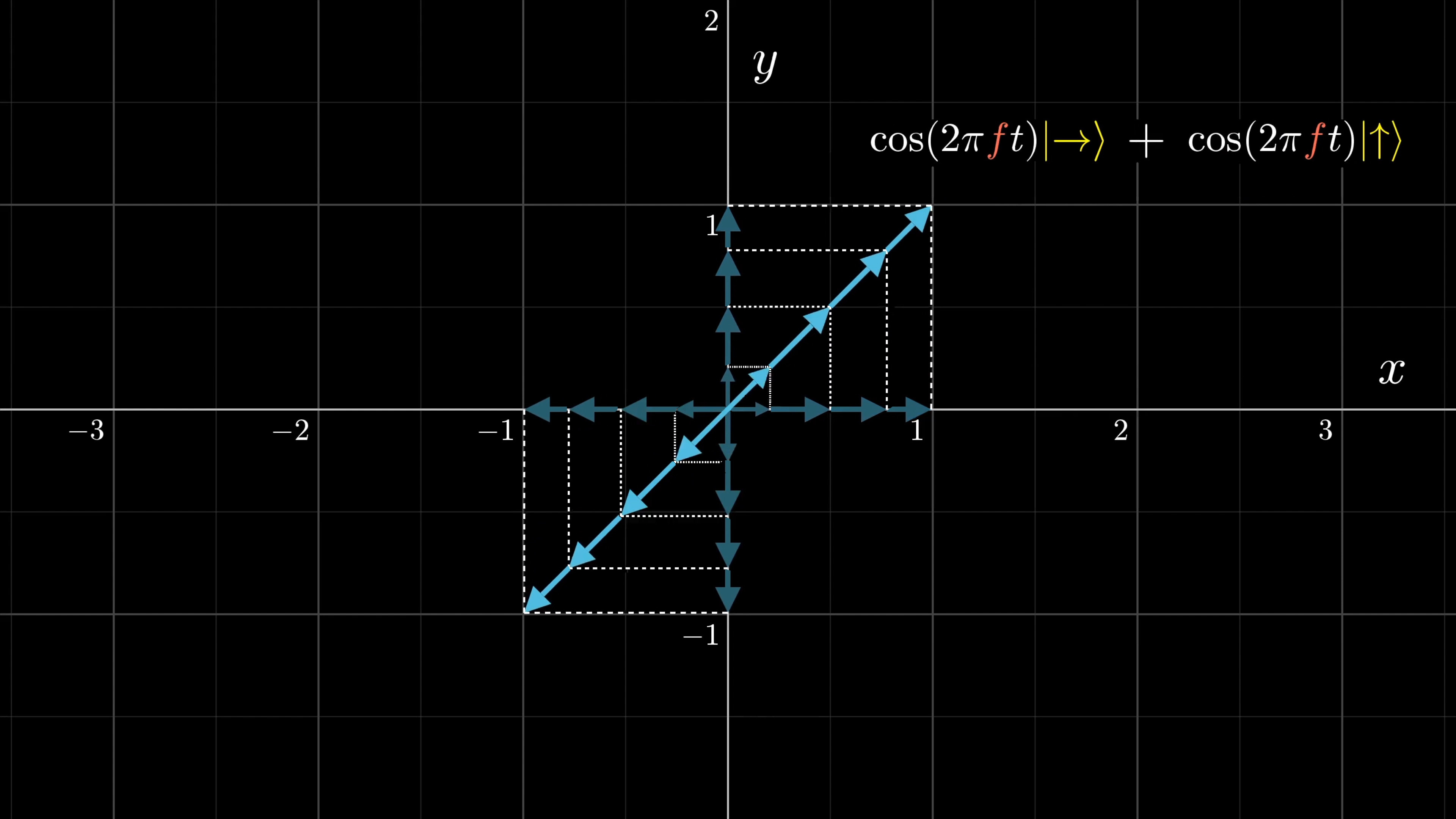

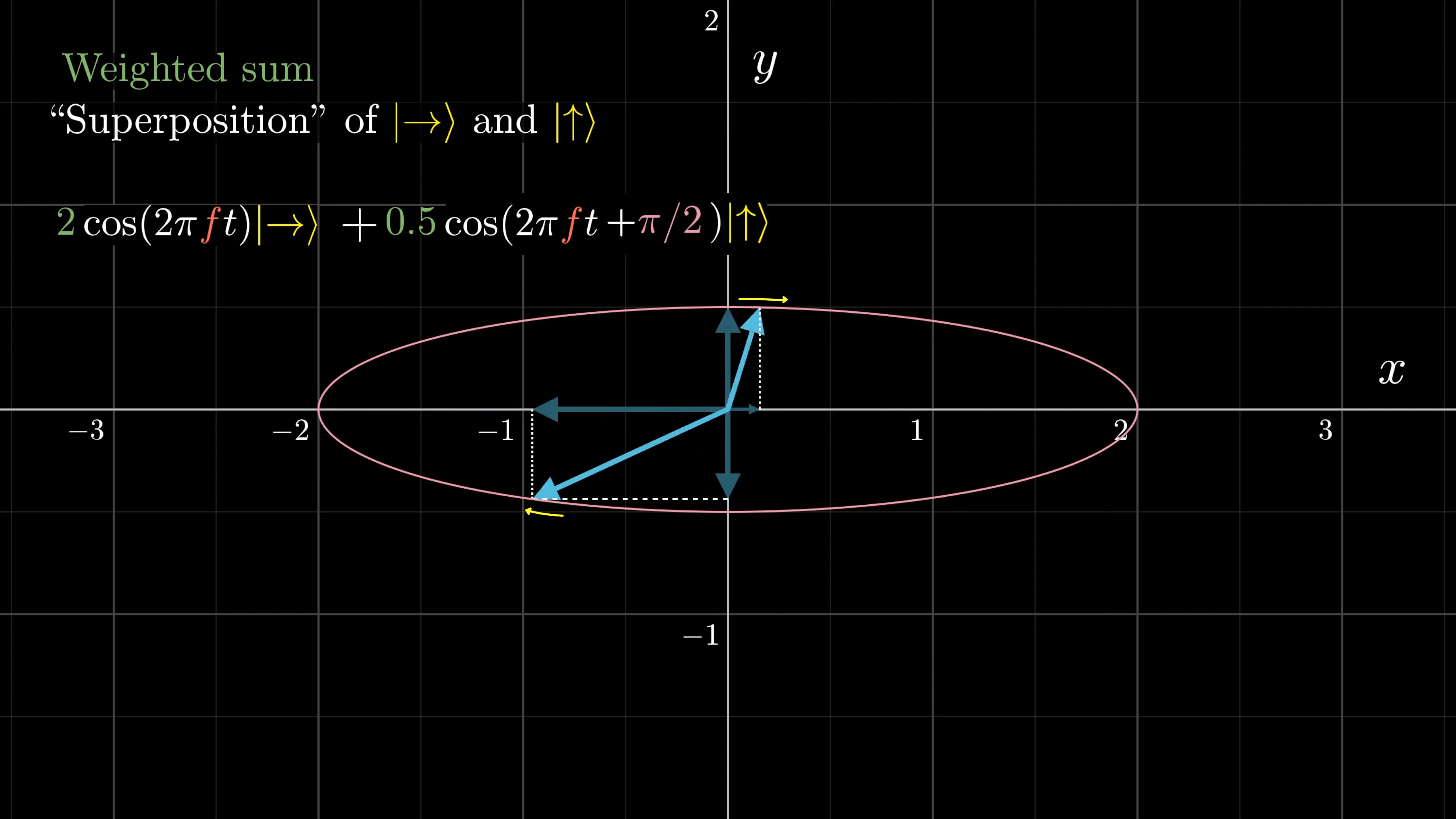

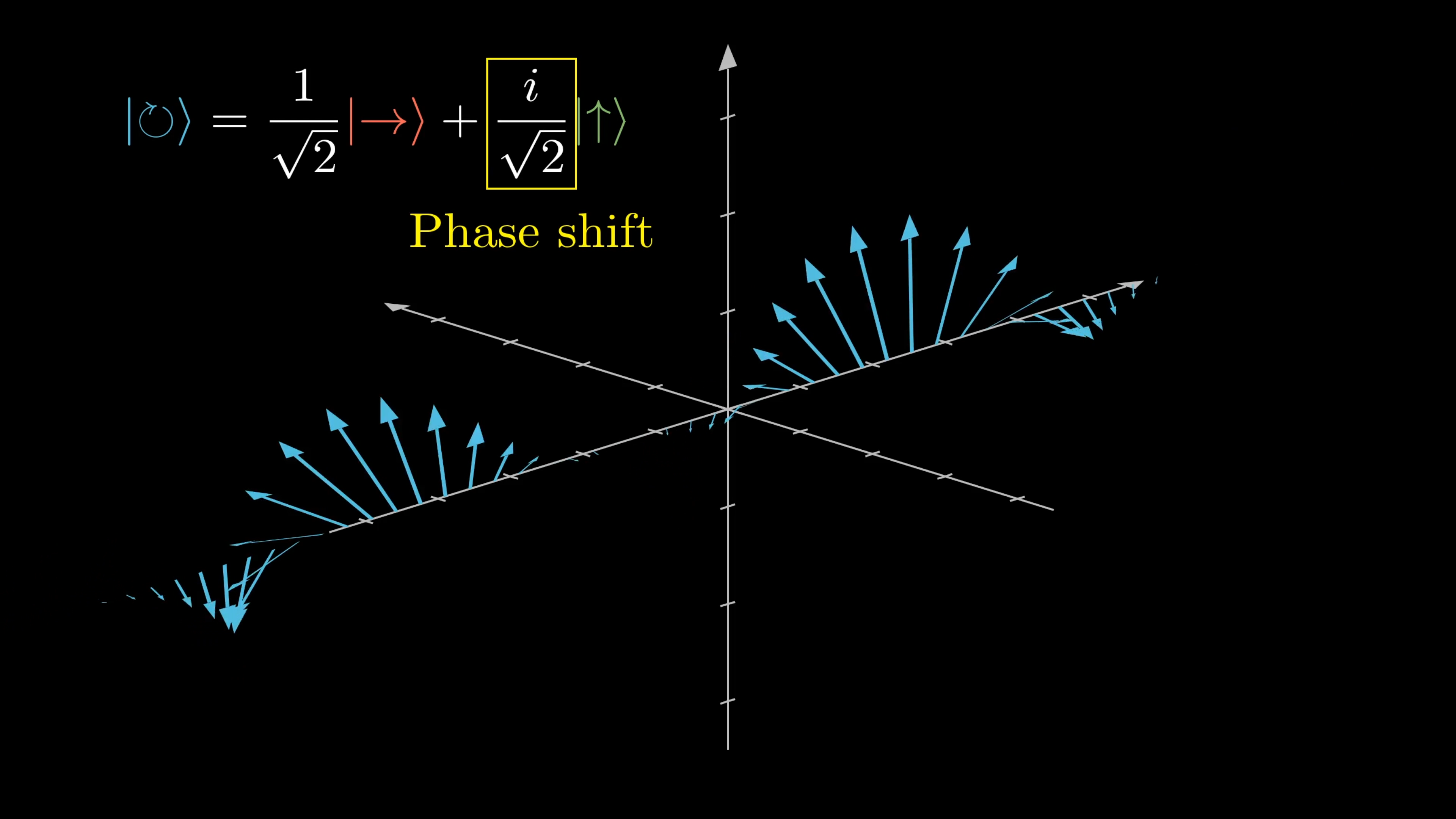

The resulting superposition is a wave wiggling in the diagonal direction. But if the horizontal and vertical components were out of phase with each other, which might happen if you introduce a phase shift to one, their sum might trace out some sort of ellipse.

In the case where the phases are exactly 90 degrees out of sync with each other, and amplitudes are equal, we call this circularly polarized light. This is why it’s important to keep track not just of the amplitude in each direction, but also of the phase. It affects the way that two waves add together. That’s an important idea which carries over to quantum.

What 2D shape does this superposition trace out?

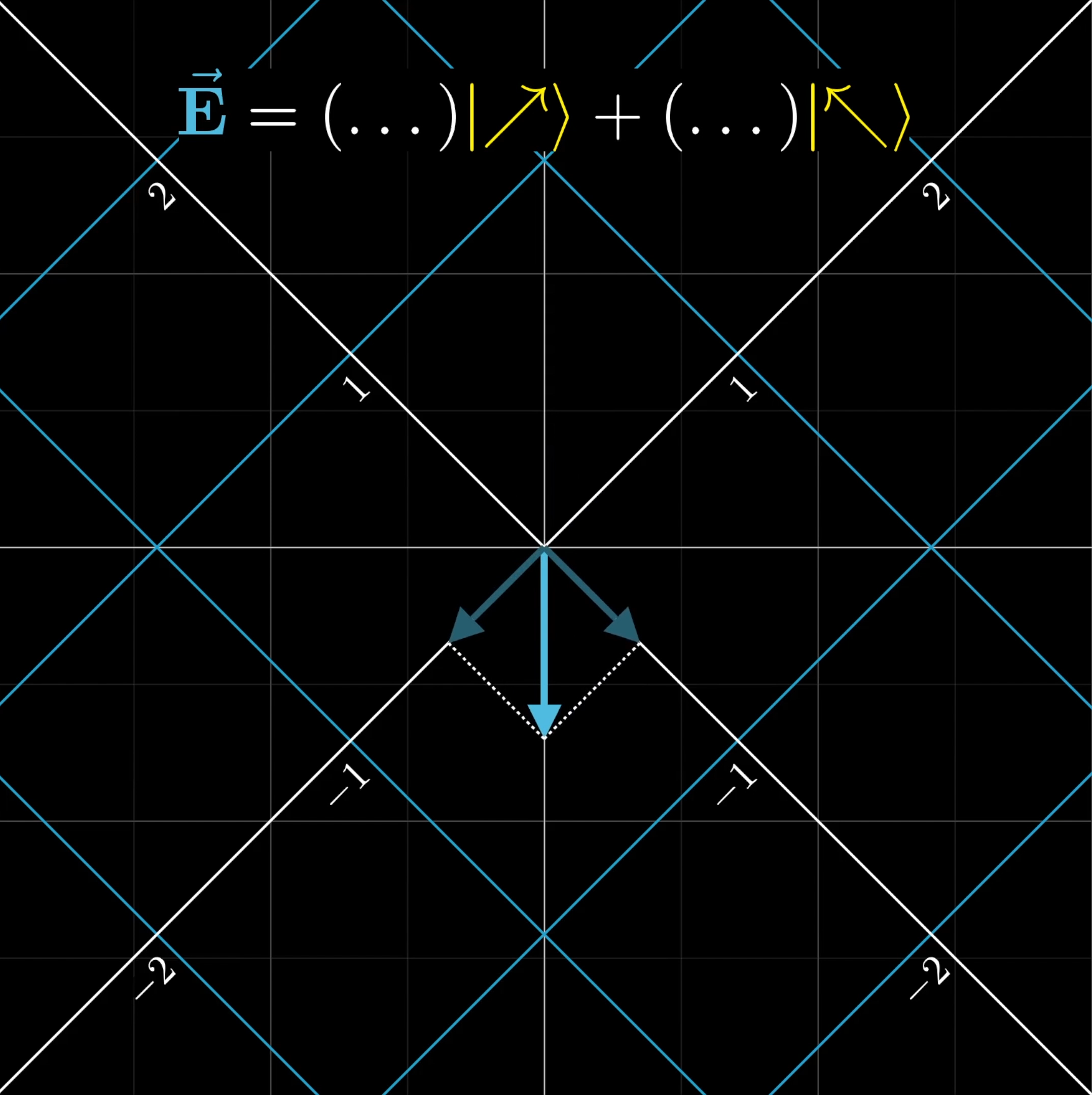

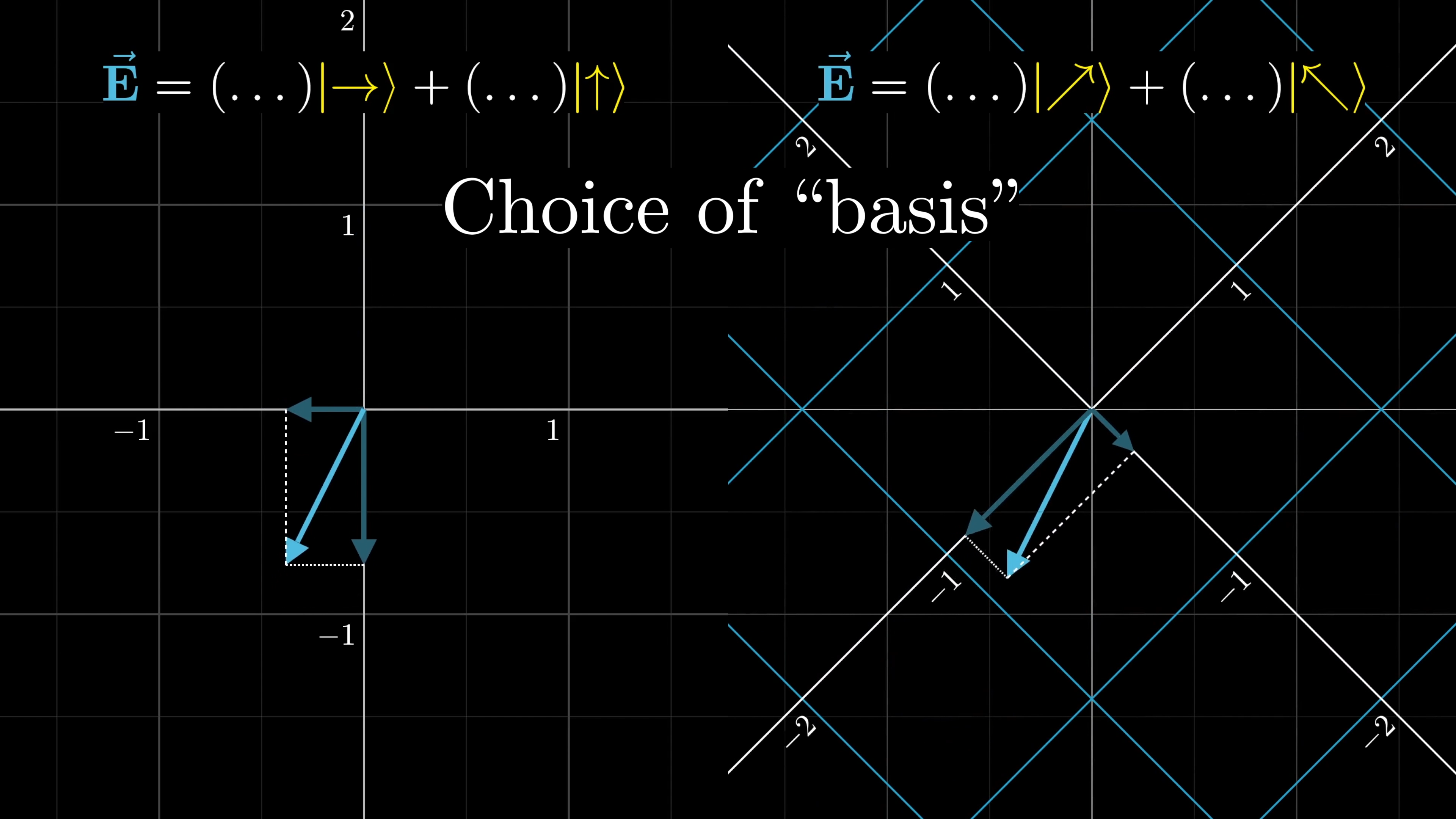

Alright, here’s another important idea: We’re describing waves by adding together horizontal and vertical components, but we could also choose to describe everything with respect to different directions.

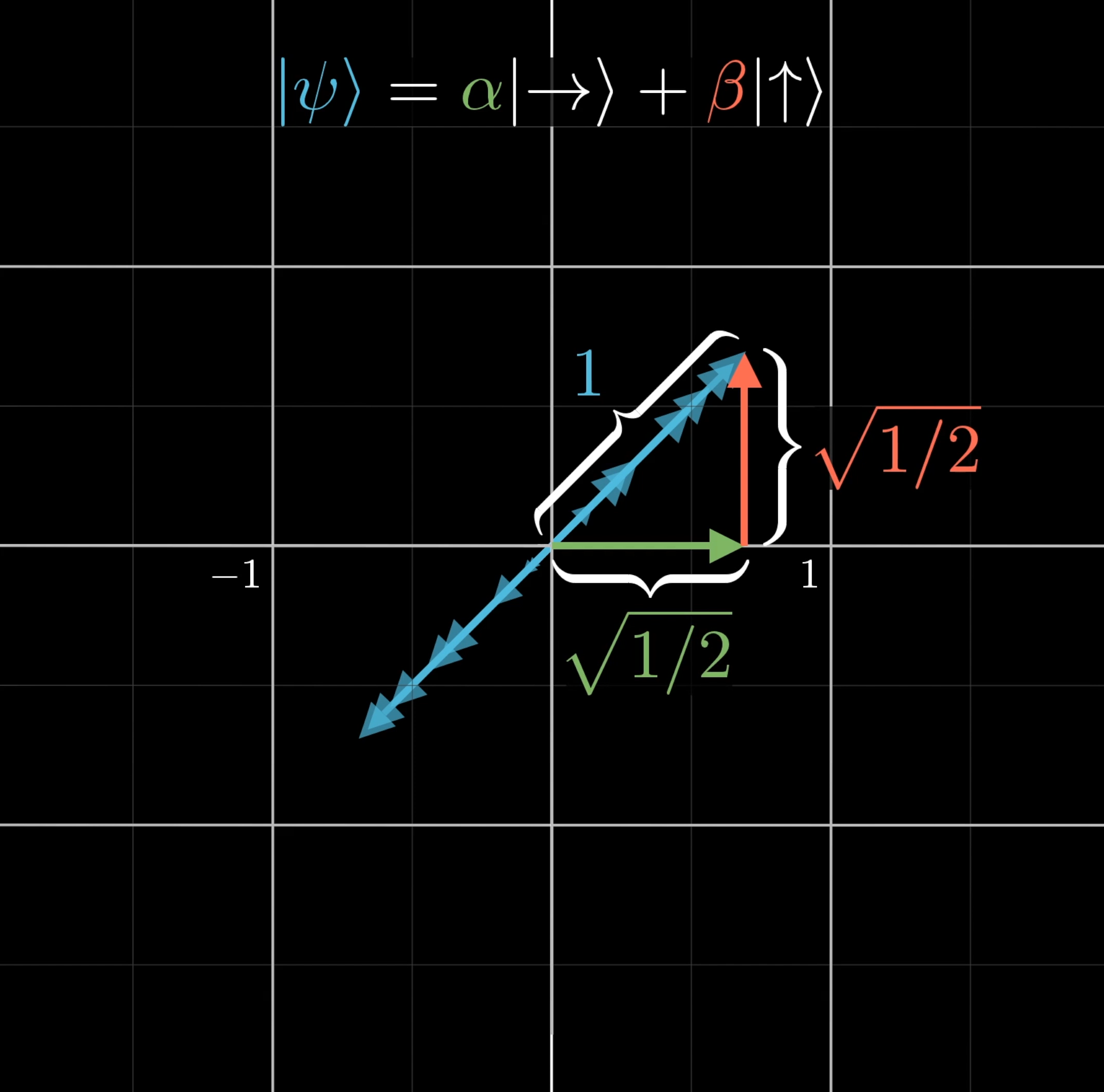

For example, you could describe waves as some superposition of the diagonal and antidiagonal directions. In that case, vertically polarized light would be a superposition of these two where both are in phase with each other, and where each has equal magnitude.

The choice of which directions you write things in terms of is called a “basis”. Which basis is nicest to work with typically depends on what you are actually doing with the light.

What is a Polarizer?

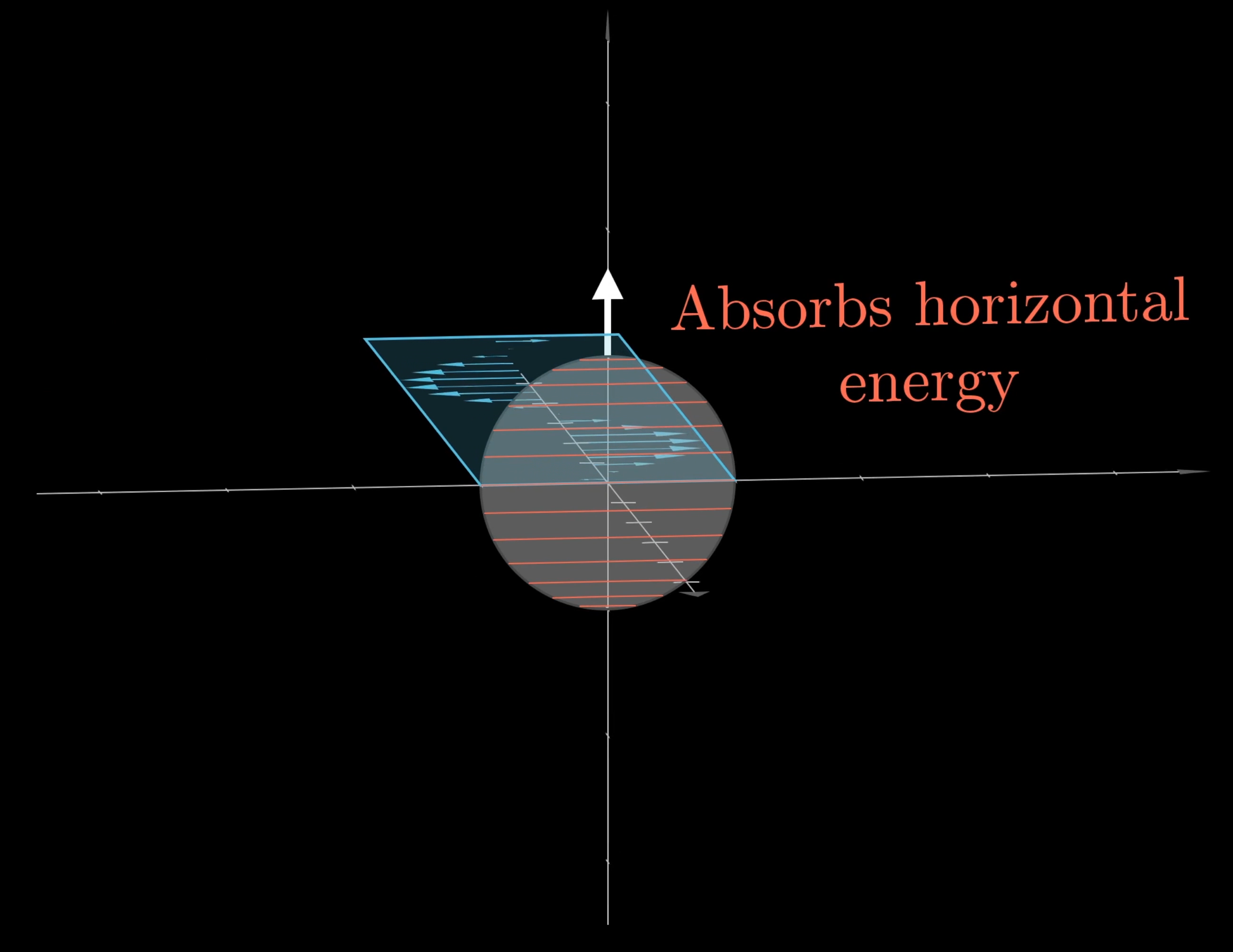

If you have a polarizing filter, like that from a set of polarized sunglasses, the way these work is by absorbing the energy from electromagnetic oscillations in some direction. A vertically oriented polarizer will absorb all the energy from these waves in the horizontal direction. At least, classically that’s how you might think about it.

If you are analyzing light passing through a filter like this, it’s nice to describe it with respect to the horizontal and vertical directions. So you can say that what passes through the filter is the vertical component of that wave.

This polarizer only lets through the vertical component of the wave. When the wave is almost sideways, the horizontal component is much larger, so the resulting wave is small. When the wave is nearly vertical, the resulting wave is almost as large.

But with a filter oriented diagonally, it might be more convenient to describe your wave as a superposition of the diagonal and antidiagonal directions.

Notation of Waves, Quantum Style

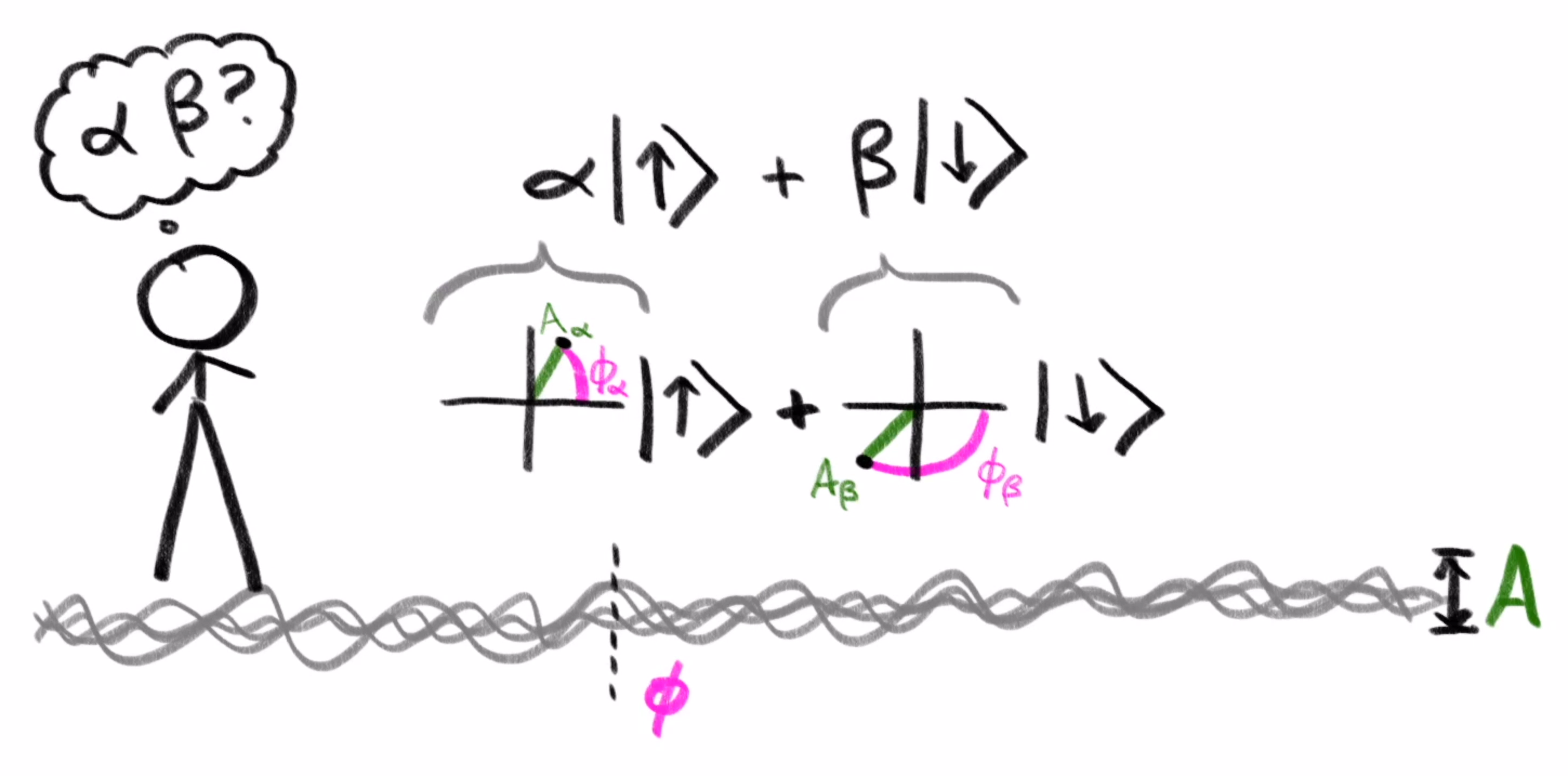

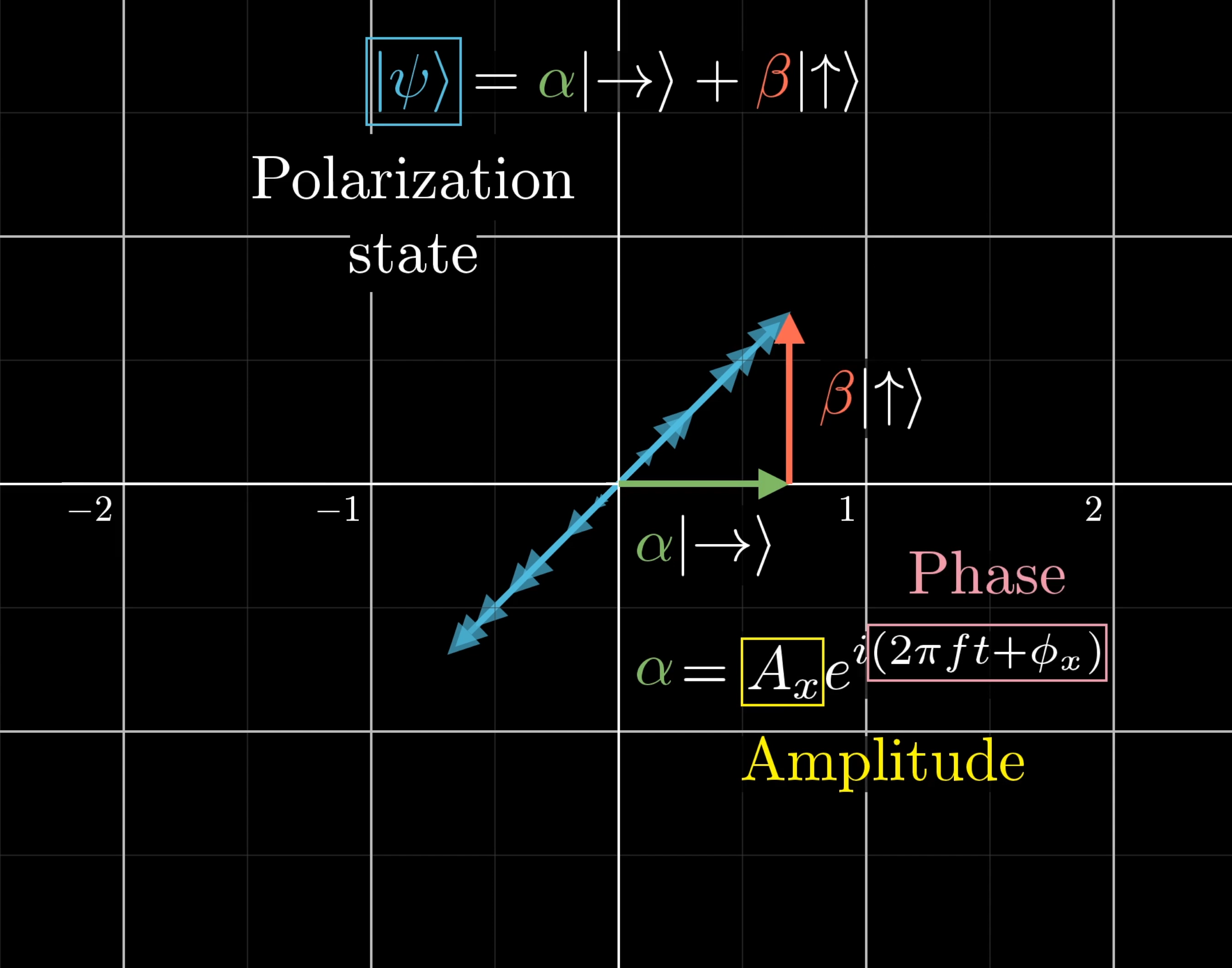

These ideas will carry over almost word for word to the quantum case: Quantum states, much like this wiggling direction of our wave, are described as a superposition of multiple base states. There are often many choices for what base states to use. And just like with classical waves, the components of such a superposition will have both an amplitude and a phase of some kind.

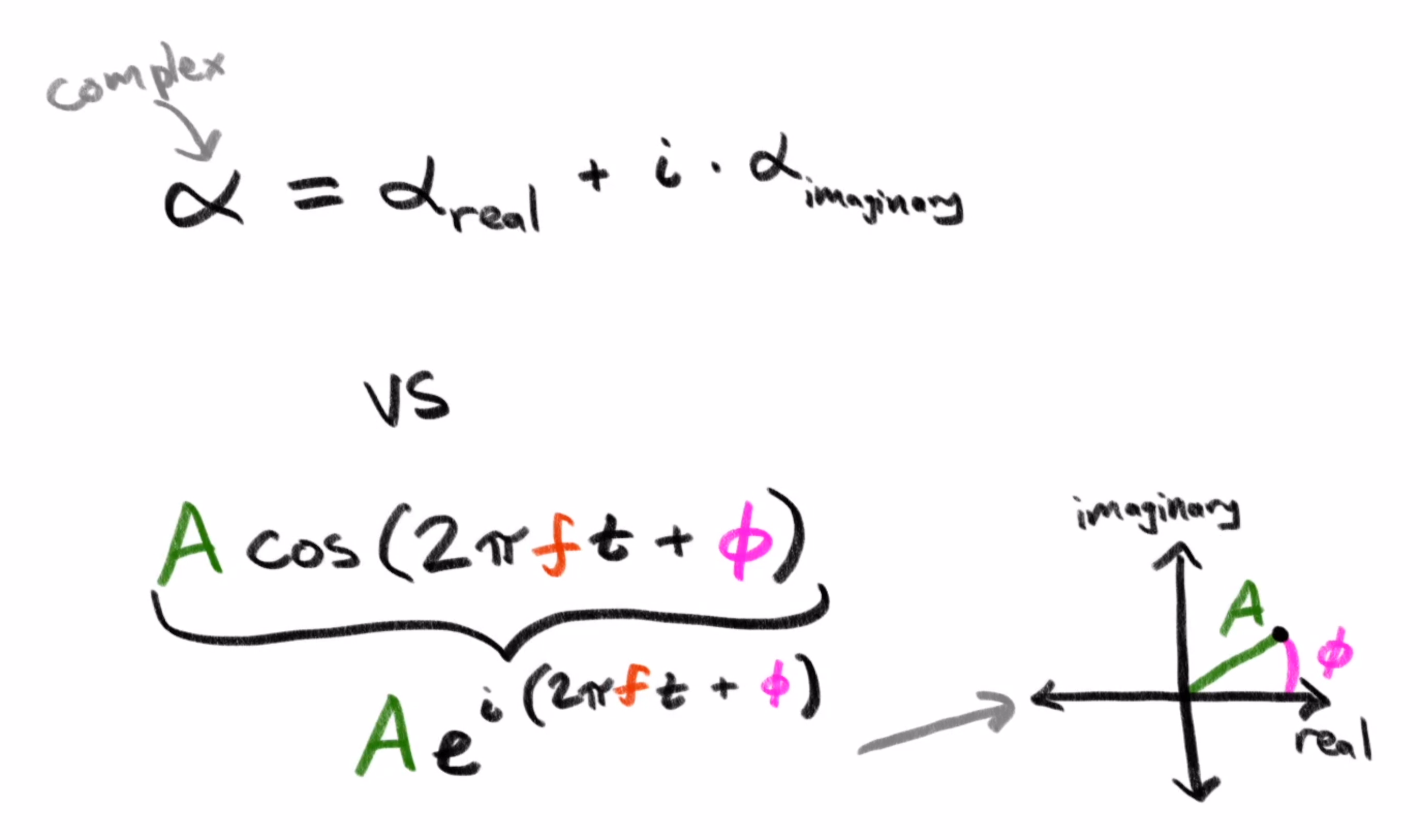

For those of you who do read more into quantum mechanics, you’ll find that these components are actually given using a single complex number, rather than a cosine expression like this one. One way to think of this is that complex numbers are just a very convenient and natural way to encode an amplitude and a phase with a single value.

That can make things a little confusing, because it’s hard to visualize a pair of complex numbers, which is what would describe a superposition of two base states. But just remember that the use of complex numbers throughout quantum physics is really a result of the underlying wave mechanics, because of this need to encapsulate the amplitude and the phase for each direction.

If the classical wave described below went through a diagonal polarizer aligned with , how would we describe the resulting wave?

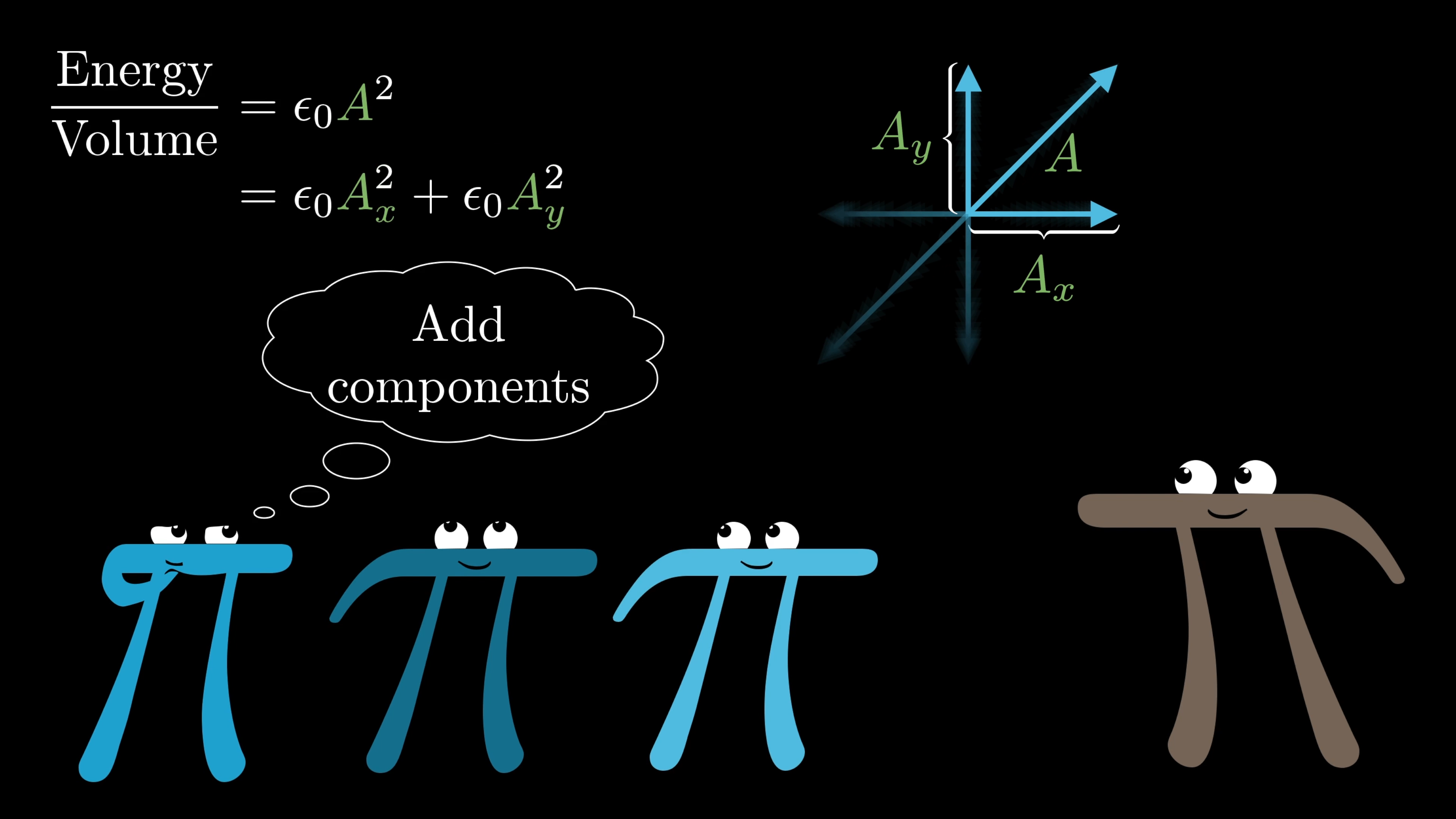

Okay, just one quick point before getting to the quantum. Look at one of these waves, and focus just on the electric field portion like we were before. Classically, the energy density of a wave like this is proportional to the square of its amplitude. Notice, by the way, how well this lines up with the Pythagorean theorem.

If you describe this wave as a superposition of a horizontal component with amplitude , and a vertical component with amplitude , then its energy density is proportional to .

You can think of this either because you’re adding up the energies of each component of the superposition, or because you’re figuring out the new amplitude using the Pythagorean theorem, and taking its square. Isn’t that nice?

Bridging to Quantum Physics

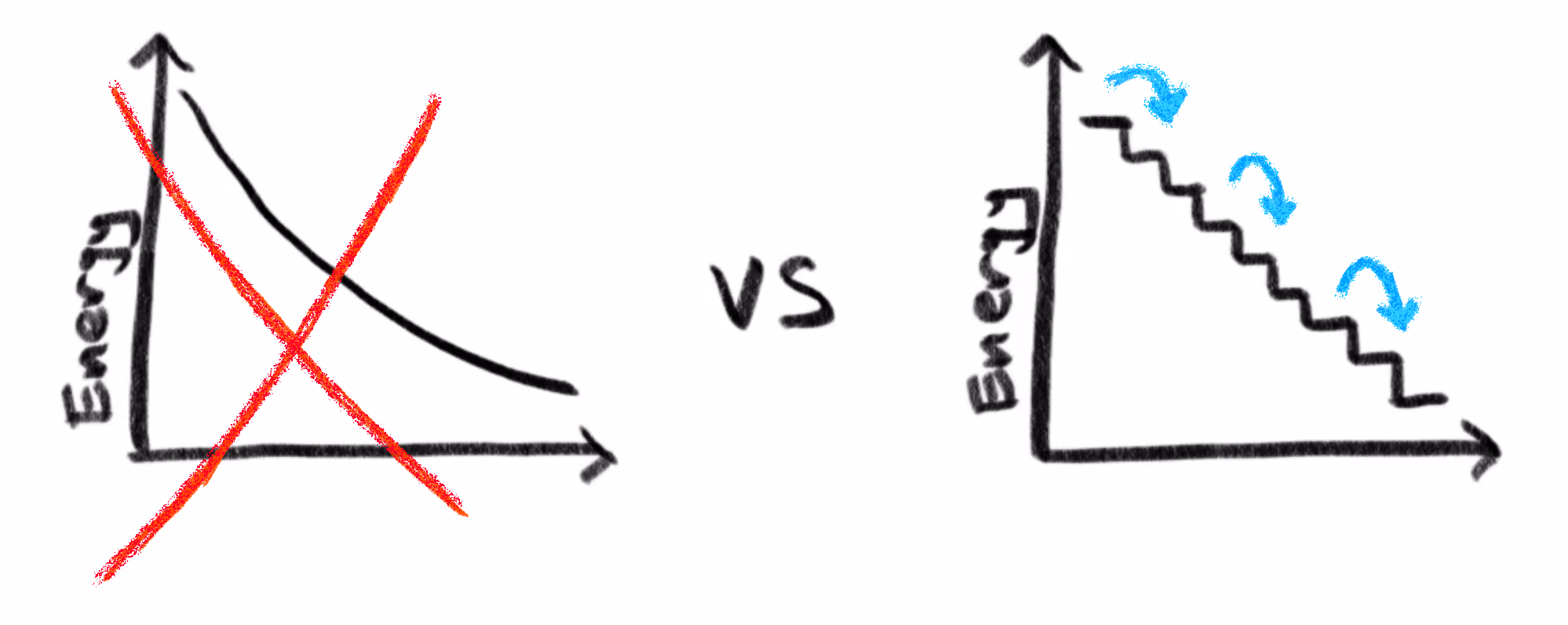

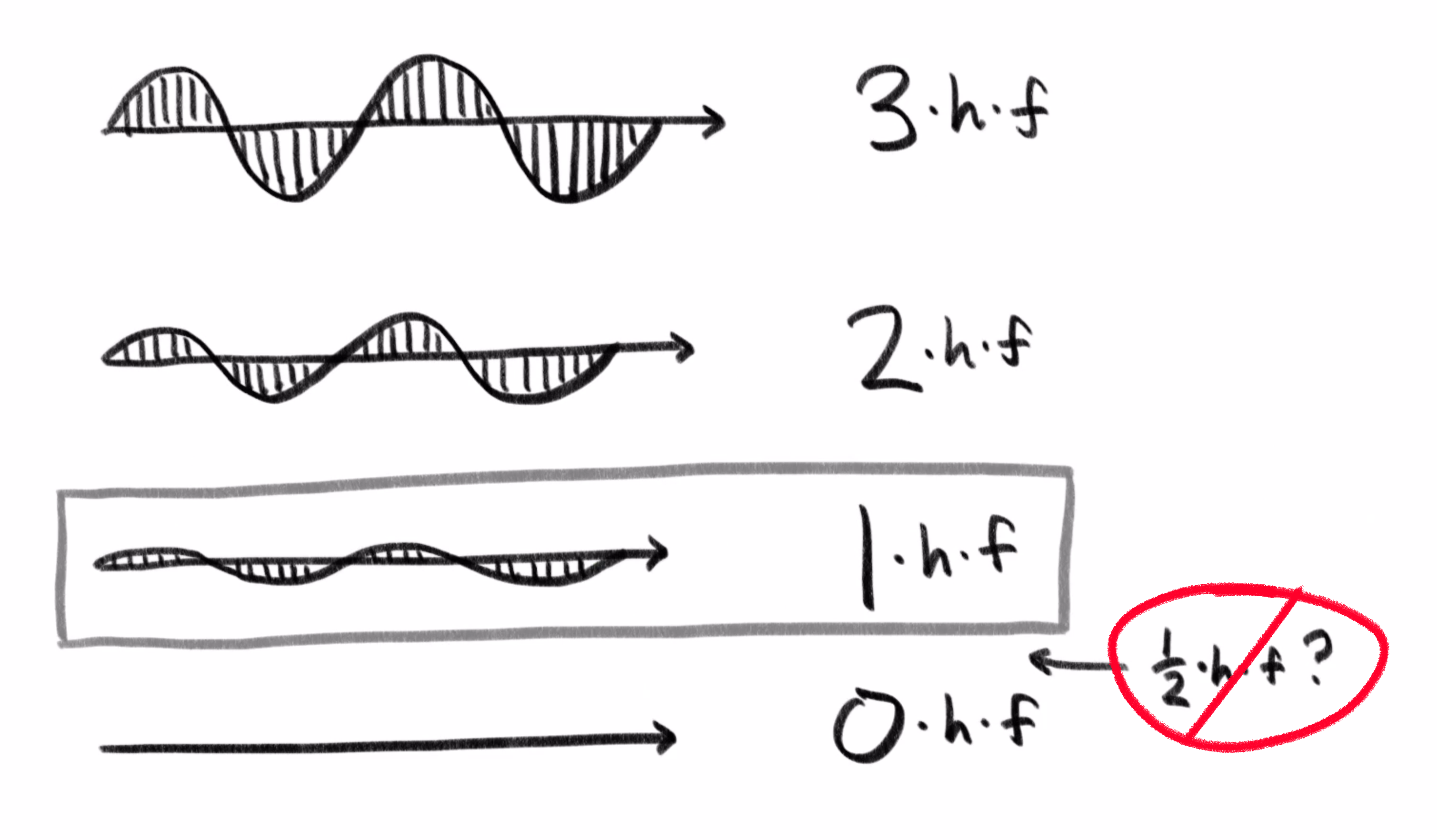

In the classical understanding of light, you should be able to dial this energy up and down continuously by changing the amplitude of the wave. But what physicists started to notice in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was that this energy actually seems to come in discrete amounts.

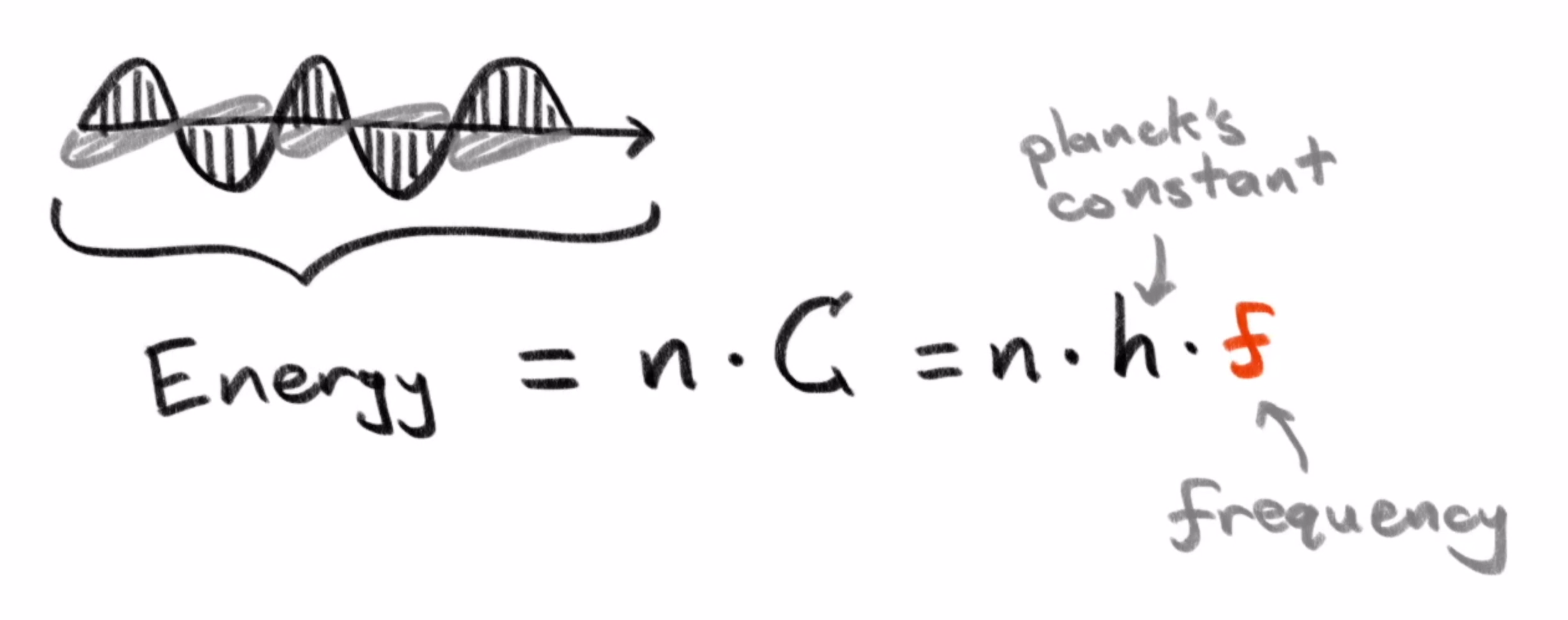

Specifically, the energy of one of these electromagnetic waves always seems to come as an integer multiple of a specific constant times the frequency of that wave. The frequency being the value we’ve been using to describe the rate at which the phase changes. We’ll now call this specific constant , known as Planck's constant.

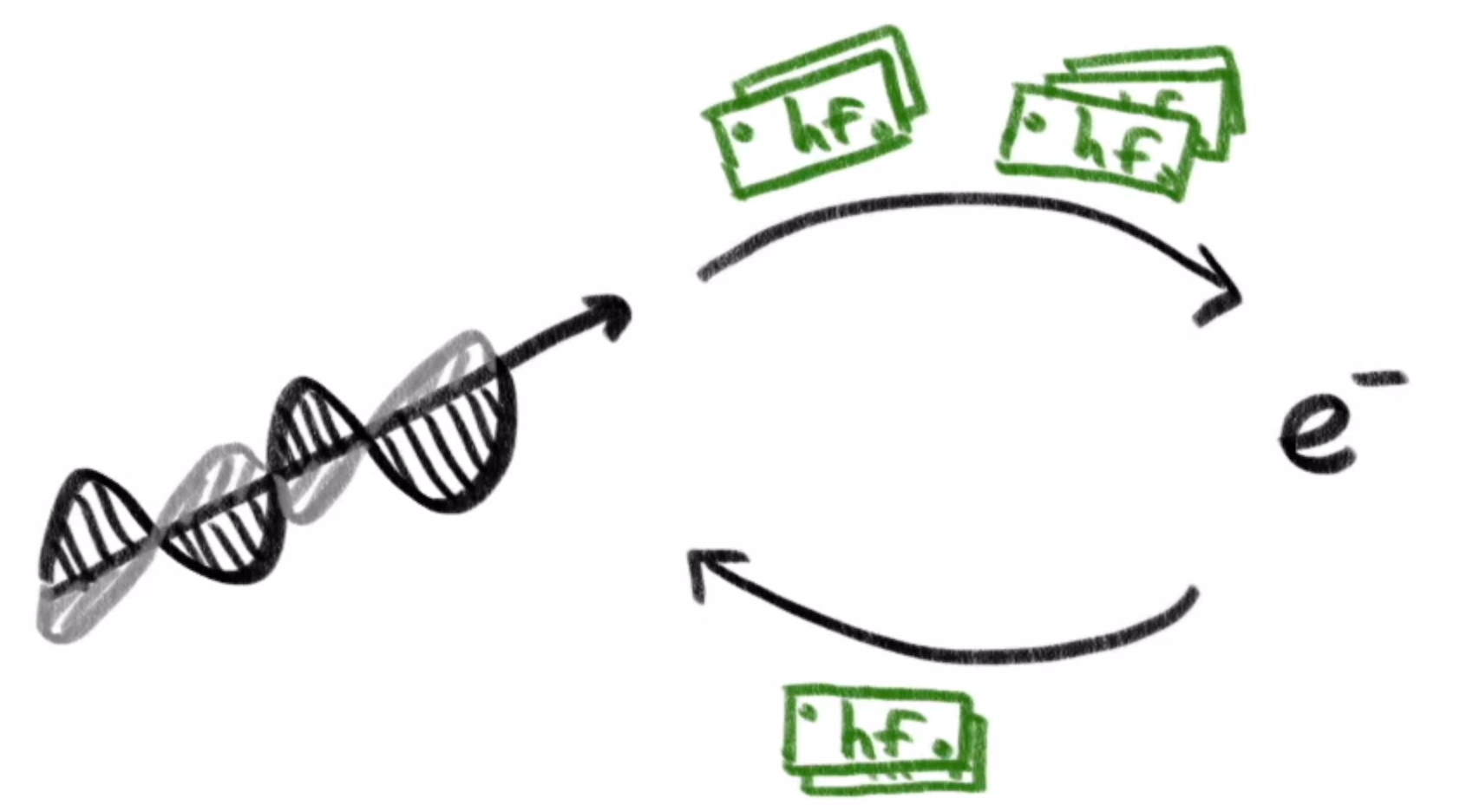

Physically, what this means is that whenever this wave trades its energy with something else, like an electron, the amount of energy it trades off is always an integer multiple of times its frequency .

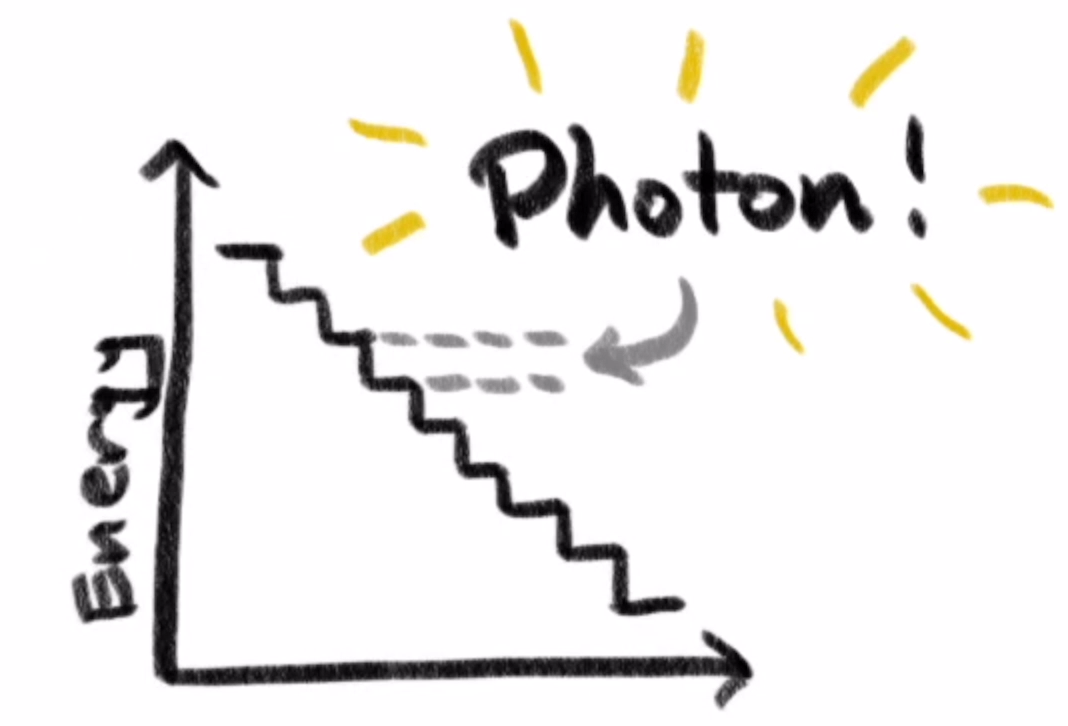

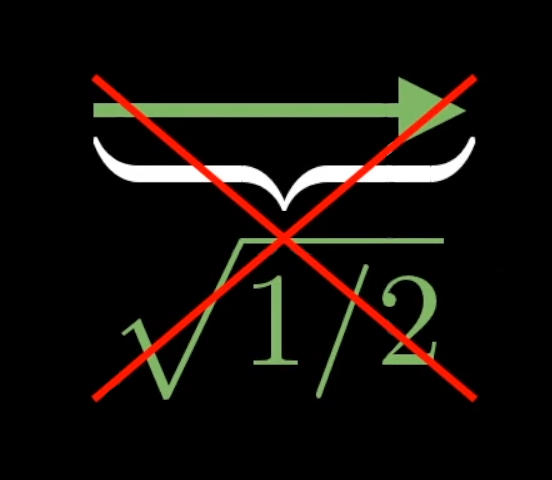

Importantly this means there is some minimal nonzero energy level for the wave of a given frequency: . If you have an electromagnetic wave with that frequency and energy, you cannot make it smaller without eliminating it entirely.

That feels weird when the conception of a wave is a nice, continuously oscillating vector field. But this is a fundamental truth that early 20th century experiments started to expose. Do you know what they called an electromagnetic wave with this minimal possible energy? A photon!

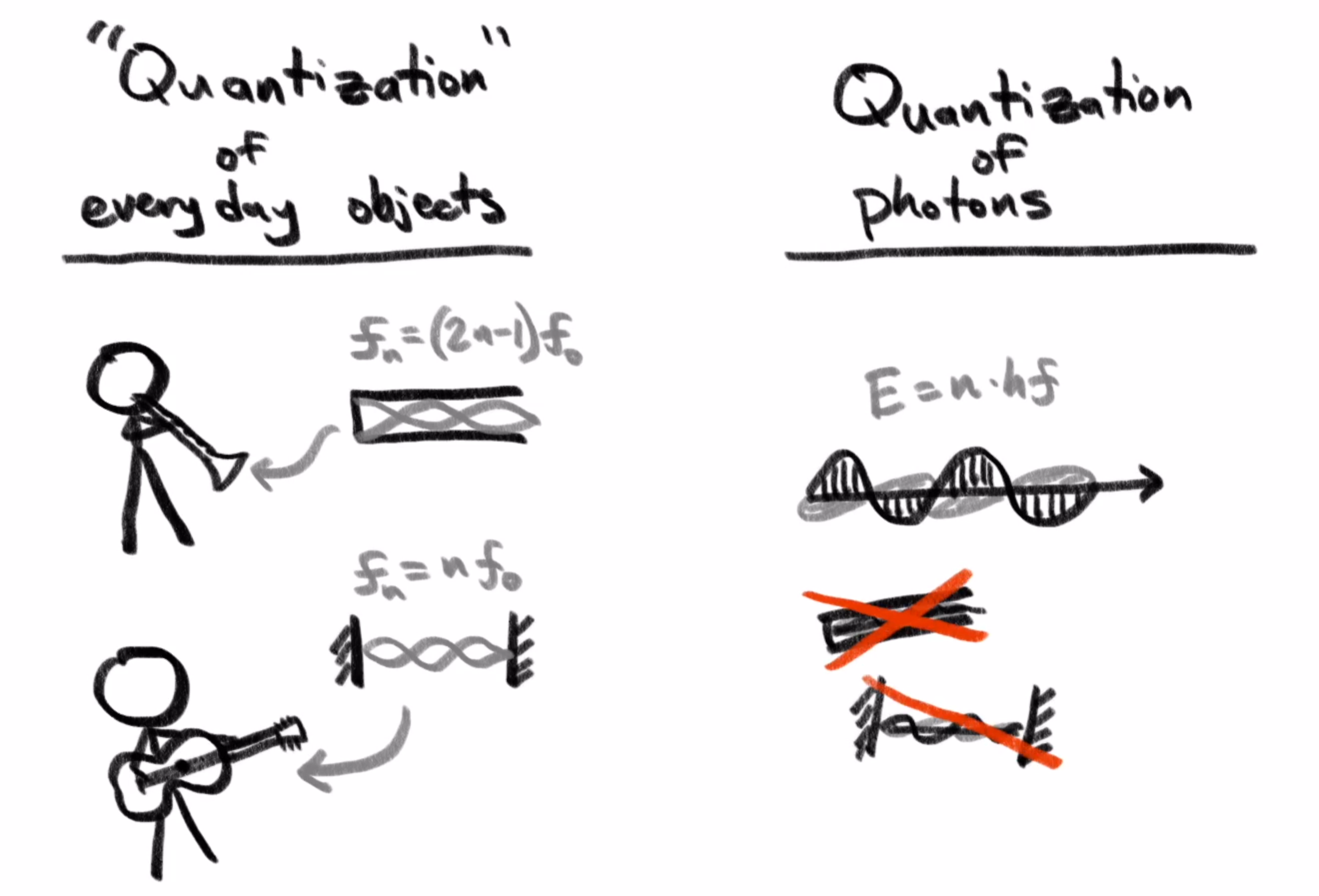

However, this phenomenon is actually common in waves when they’re constrained in certain ways, like in pipes, or an instrument string: it’s called “harmonics”. What’s weird is that electromagnetic waves do this in free space even when they’re not constrained.

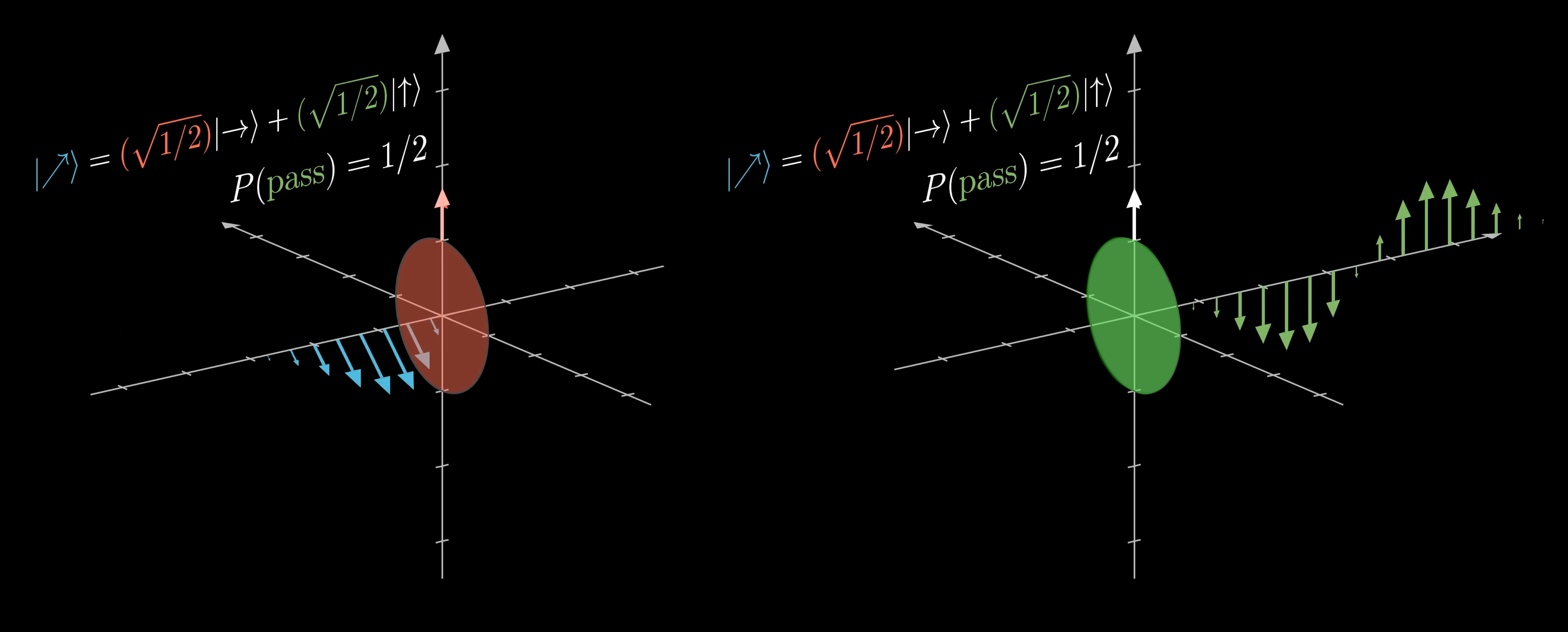

But as previously said, the math used to describe a classical electromagnetic wave carries over to describing a photon. It might have a 45 degree diagonal polarization, which can be described as a superposition of a purely horizontal state and a purely vertical state, where each of these components has an amplitude and phase.

And with a different choice of basis, this same state can be expressed as a superposition of two other directions. All of this is stuff you’ll see if you start reading more into quantum mechanics.

But this superposition has a different interpretation than before… and it has to. Let’s say you were thinking of this diagonally-polarized photon somewhat classically, and you described its amplitude as unit. This would make the hypothetical amplitudes of its left and right components each the square root of one half: .

The energy of a photon is the special constant times its frequency. Because in a classical setting energy is proportional to the square of the amplitude of this wave, it’s tempting to think of half that energy being in the horizontal component, and half being in the vertical component.

But waves of this frequency cannot have half the energy of the photon. I mean, the whole novelty of quantum here is that energy comes in these discrete, indivisible chunks. So these components with an imagined amplitude of could not exist in isolation, and you might wonder what exactly they mean.

?!?

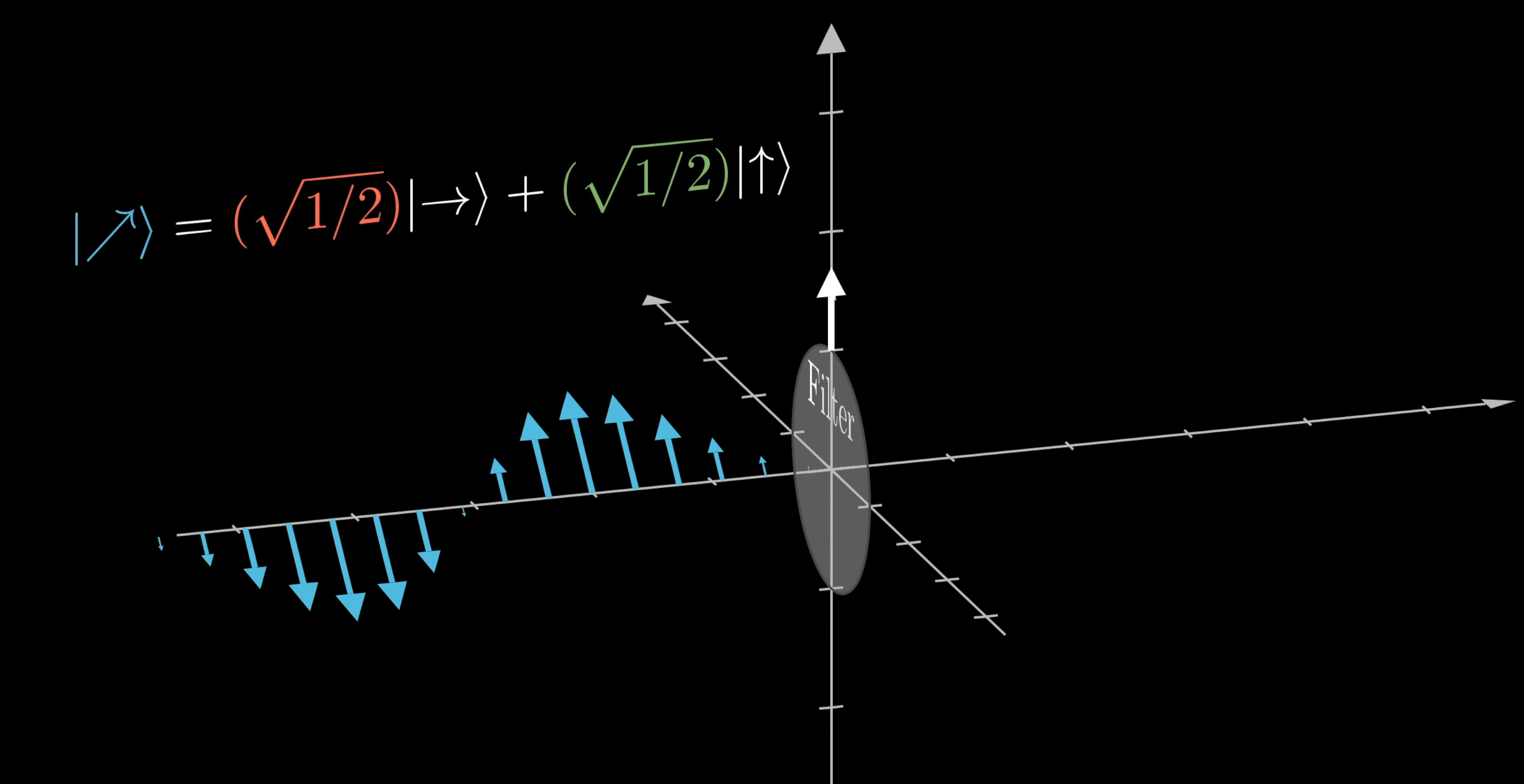

Well, let’s get experimental about it. If you take a vertically oriented polarizing filter, and shoot this diagonally polarized photon at it, what do you think will happen?

Classically, the way you’d interpret this superposition is that half its energy would be absorbed in that horizontal direction. However, energy comes in these discrete photon packets, it must either pass through with all its energy, or get absorbed entirely.

If you actually did this experiment, about half the time the photon would pass through entirely, and half the time it would get fully absorbed. And it appears to be random whether a given photon passes through or not.

If it does pass through, forcing it to make a decision will change the resulting wave so that its polarization is oriented along the filter’s direction.

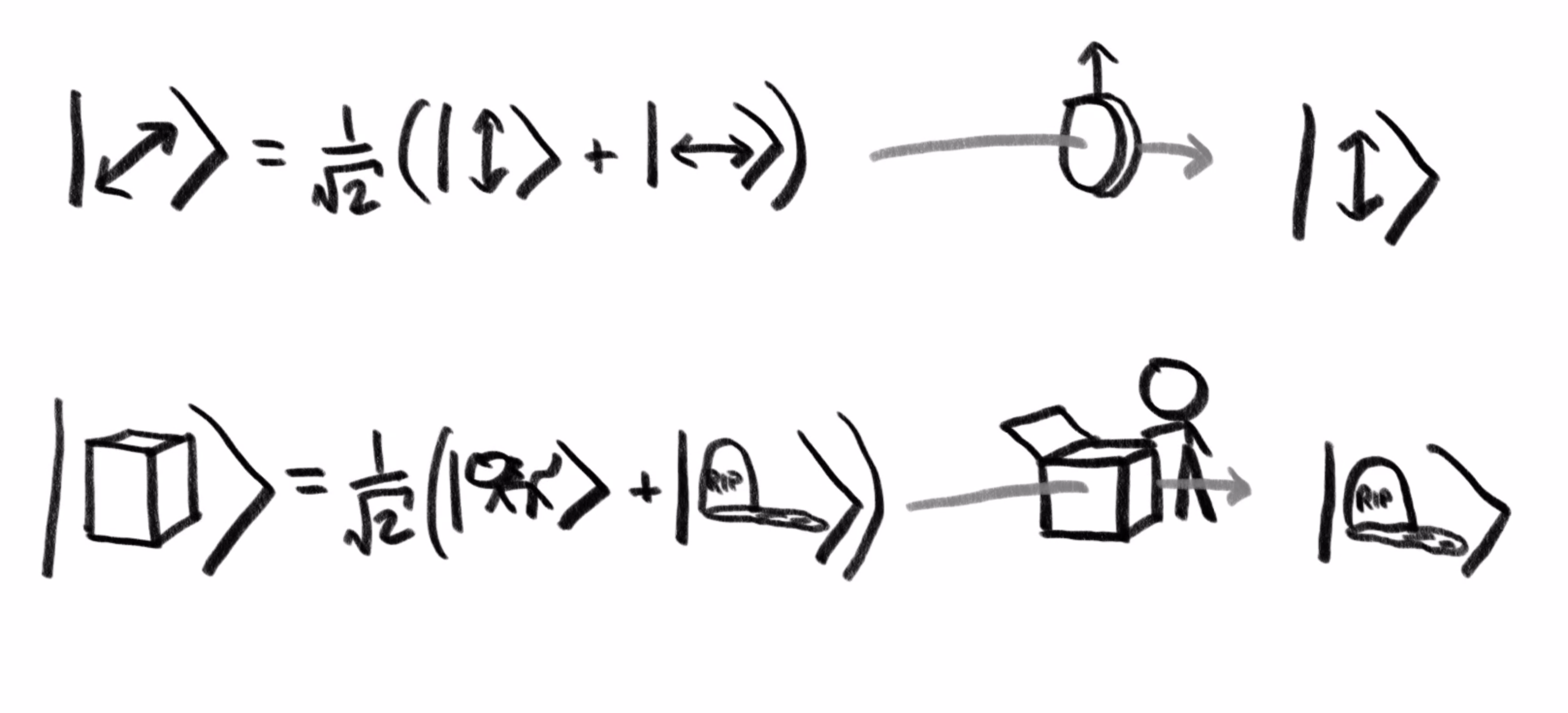

This is analogous to the classic Schrödinger’s cat setup: You have something that’s in a superposition of two states, but once you make a measurement of that superposition, it collapses so it is entirely in one state or another. When a quantum object (such as the cat in the box) is forced to interact with an observer (opening the box), the observer will only see the resulting state.

Polarizer Experiments

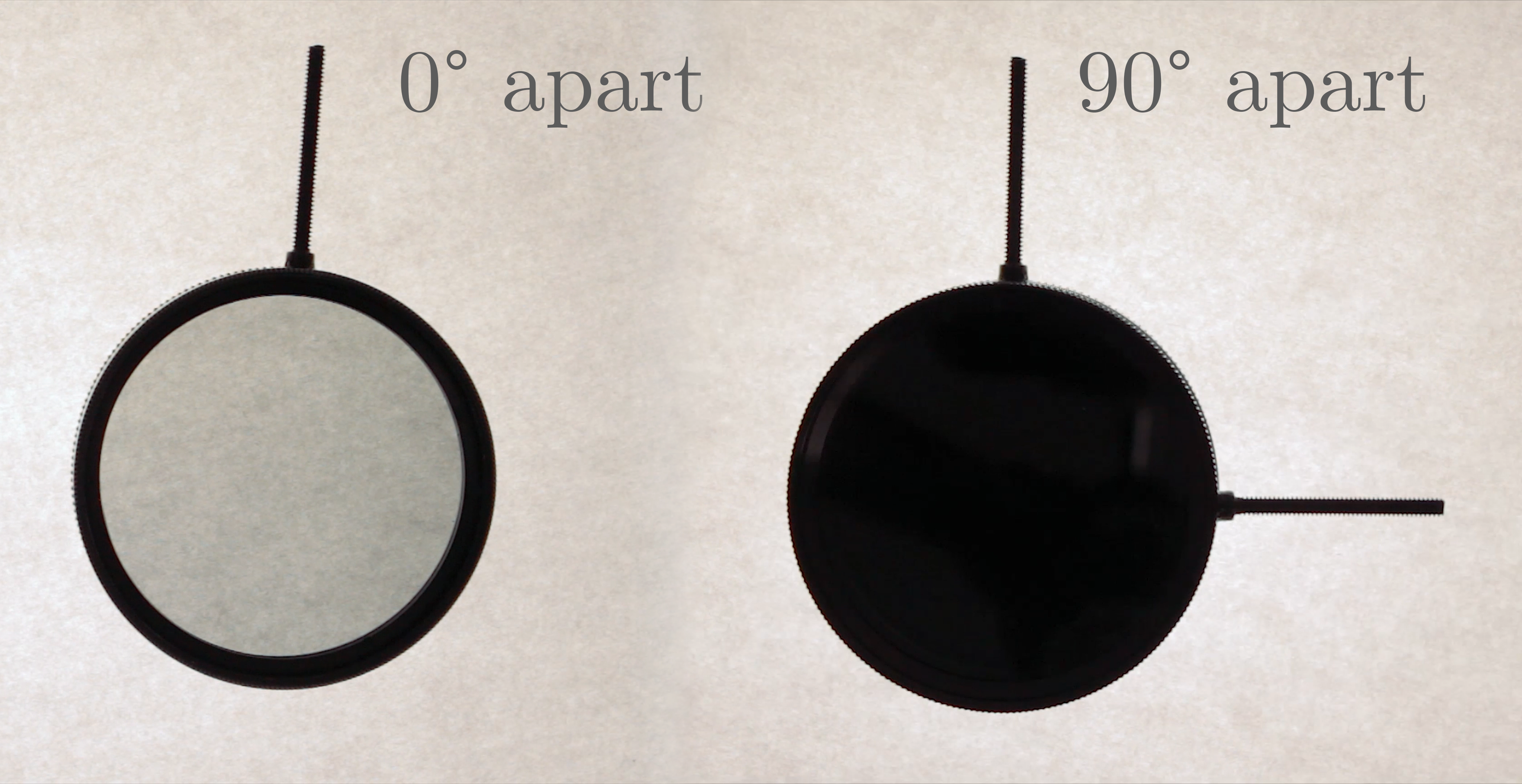

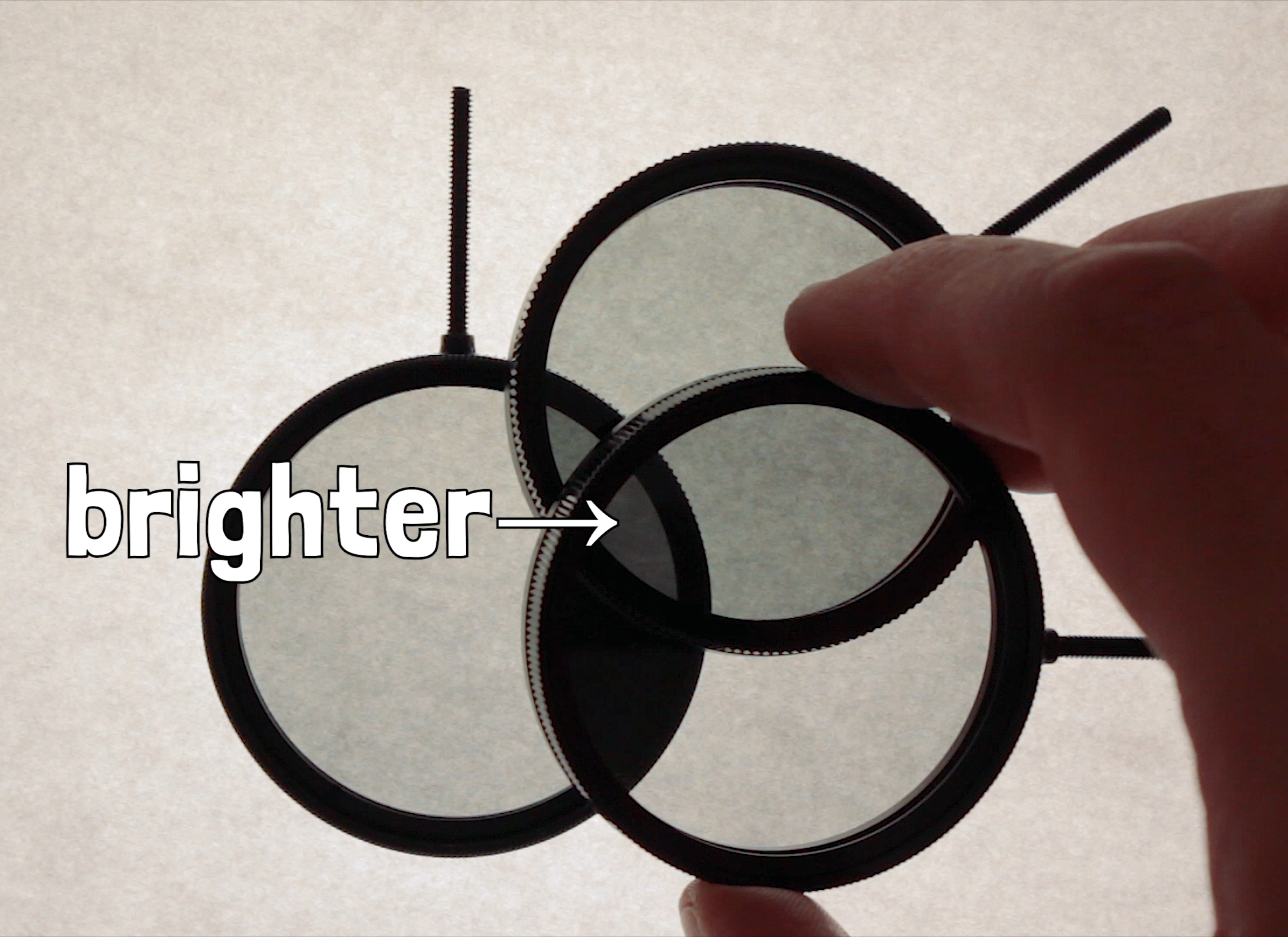

One neat way to see this in action is to take several polarized sunglasses, or some other form of polarizing filters, and start by holding two of them up between you and some light source. If you rotate them to be 90 degrees off from each other, the light source is blacked out completely.

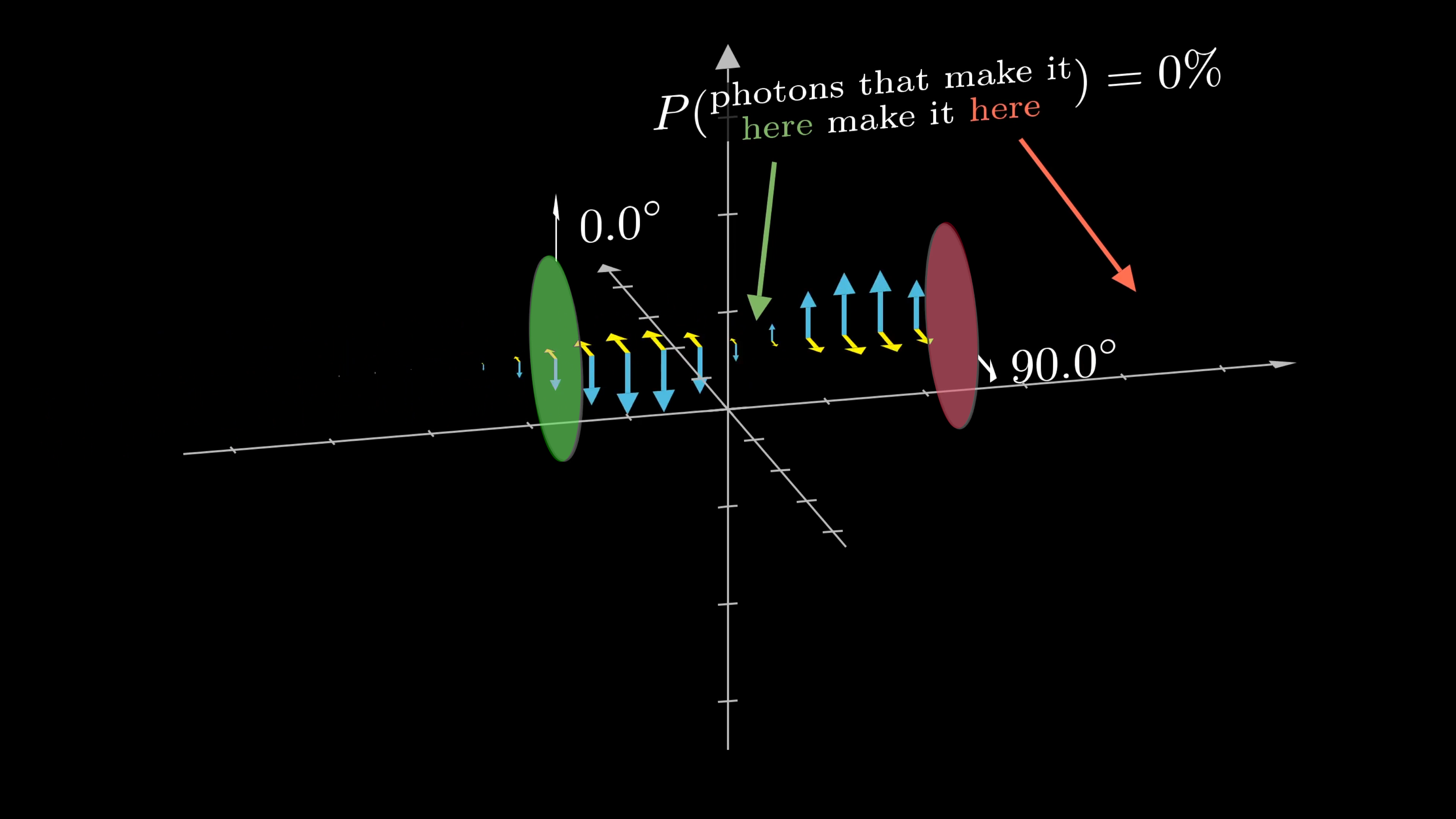

This is because all of the photons passing through the first are polarized vertically, and have a 0 percent chance of passing a filter oriented perpendicular to the first.

But if you insert a third filter oriented at 45 degrees between the two, it actually lets more light through.

What’s going on here is that 50% of the photons passing the vertical filter will also pass the diagonal filter, and when they do, they will be changed to have a purely diagonal polarization.

Once they’re in that state, they have a 50% chance of passing through the filter oriented at 90 degrees.

So even though 0% of photons passing through the first filter pass through the last with nothing in between, by introducing another filter, 25% of them pass through all three filters.

This could not be explained unless filters forced photons to change their states. The first filter forces the light to be polarized in the direction. The light which makes it past the middle filter will be polarized in the direction, and the remaining 25% will be polarized in the direction after going through the last filter.

We have a polarizer oriented at degrees, a polarizer oriented at degrees, and a polarizer oriented at degrees (90 degrees offset from ). What percent of light that goes through makes it all the way through and and out the other side?

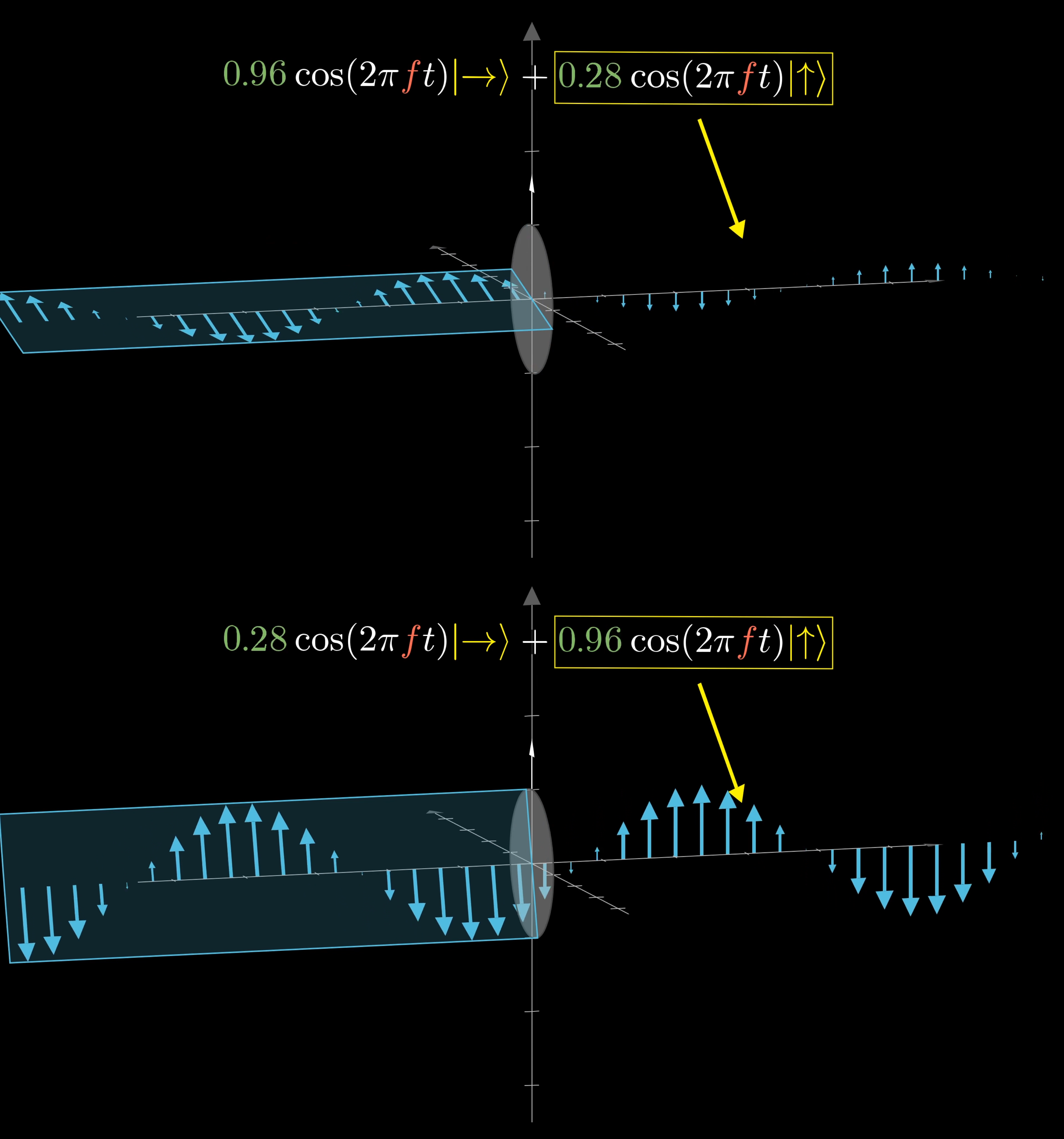

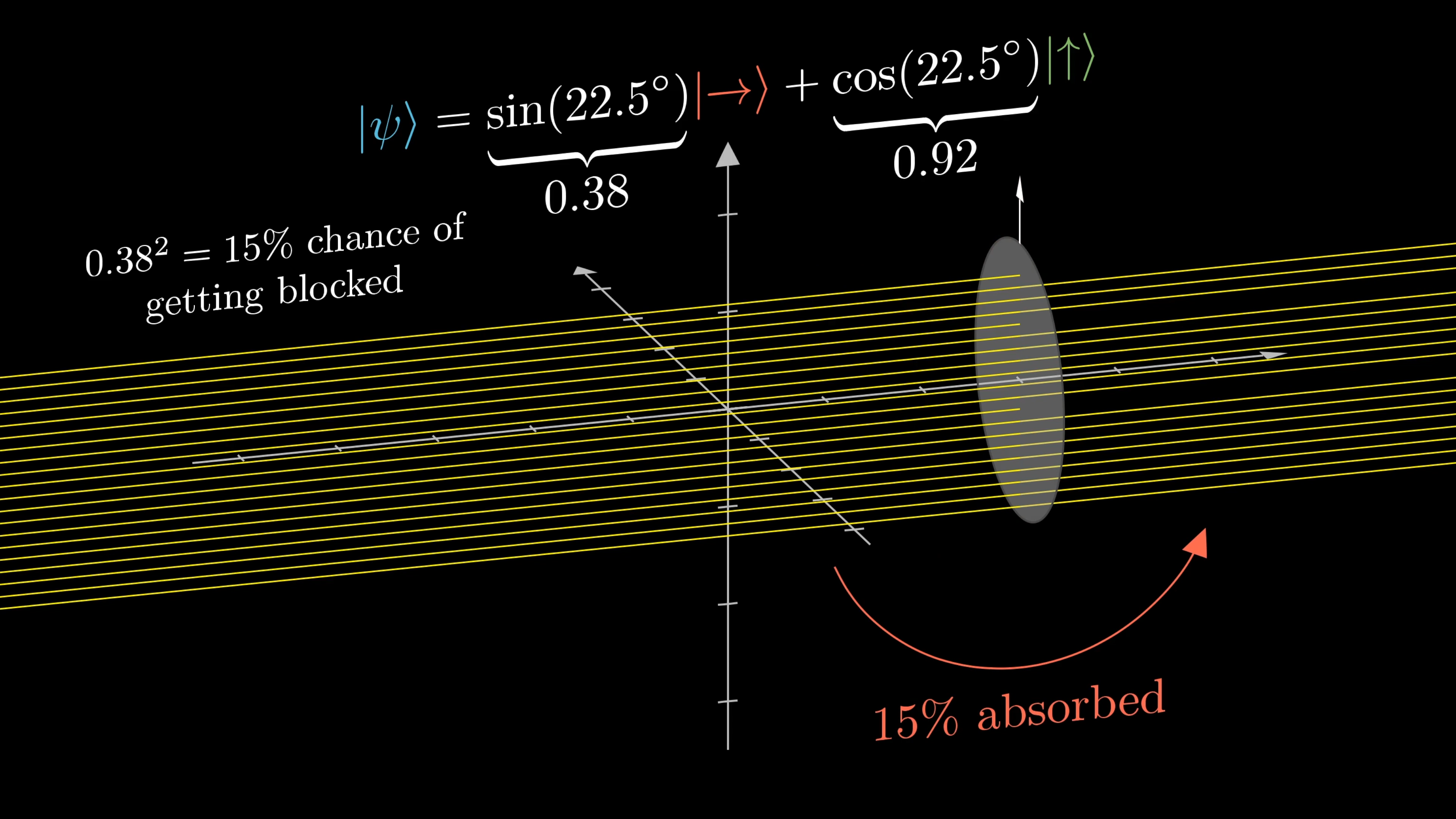

For another example, what is the probability of a photon passing through a filter degrees off from the polarization of the light? Again, it’s helpful to think of this wave as having amplitude . Its horizontal component has an amplitude of , and its vertical component has amplitude .

Classically, you might think of its horizontal component as having energy proportional to while the vertical component has energy proportional to . And classically, if you pass it through a vertical filter, the 15% of its energy in the horizontal direction would get absorbed.

But because the energy of light comes in these quanta that cannot be subdivided, instead what you observe is that 85% of the time the photon passes through entirely, and 15% of the time it gets blocked.

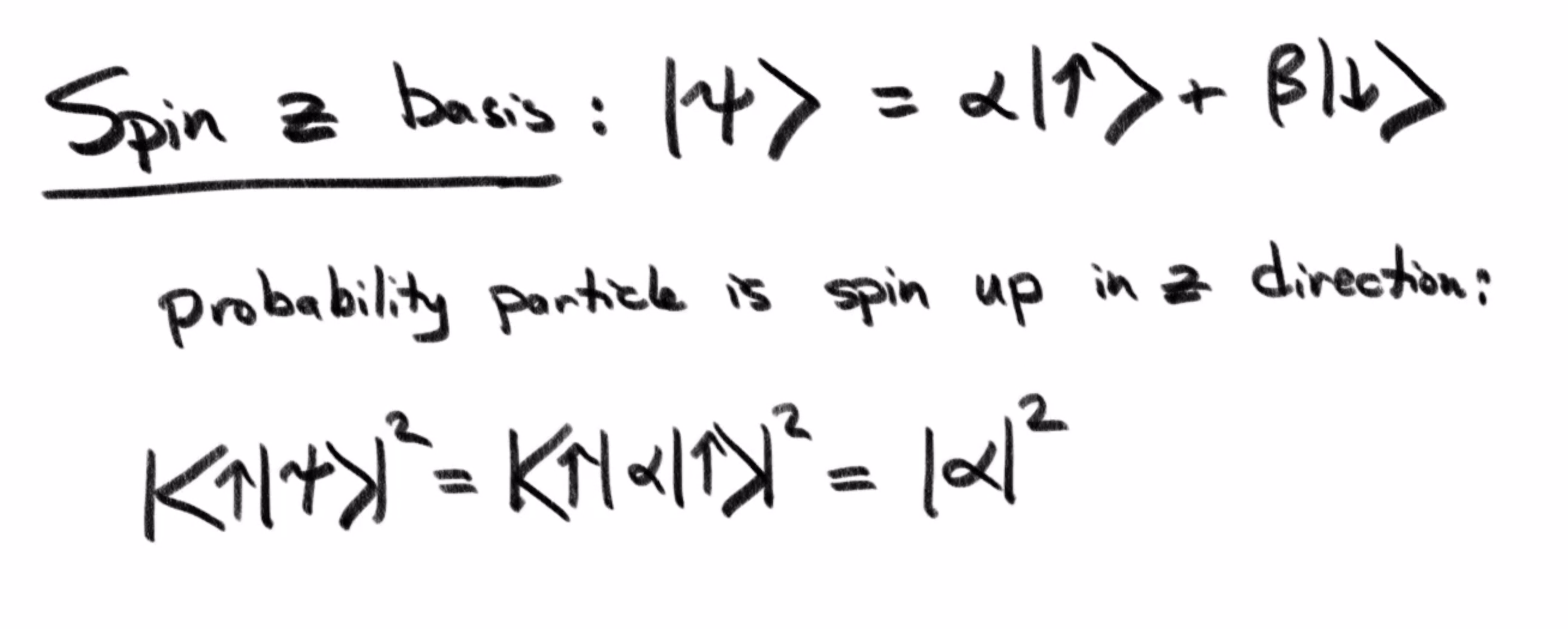

The wave equations haven’t changed, the photon is still described as a superposition of two oscillating components, each with some phase and amplitude that are often encoded as a single complex number. The difference is that classically, the squares of the amplitudes of each component in this superposition tells you the amount of that wave’s energy in each direction. But with quantized light at the minimal nonzero energy level, the squares of those amplitudes tell you the probabilities that a given photon will be found to have all its energy along one direction or not.

To display how the probability changes with the polarization of light and orientation of the filter, there is an interactive applet below. The left slider controls the incoming light's polarization angle and the right slider controls the angle of the filter.

We know an incoming photon has a 32% chance of passing through a filter. What is the angle between them?

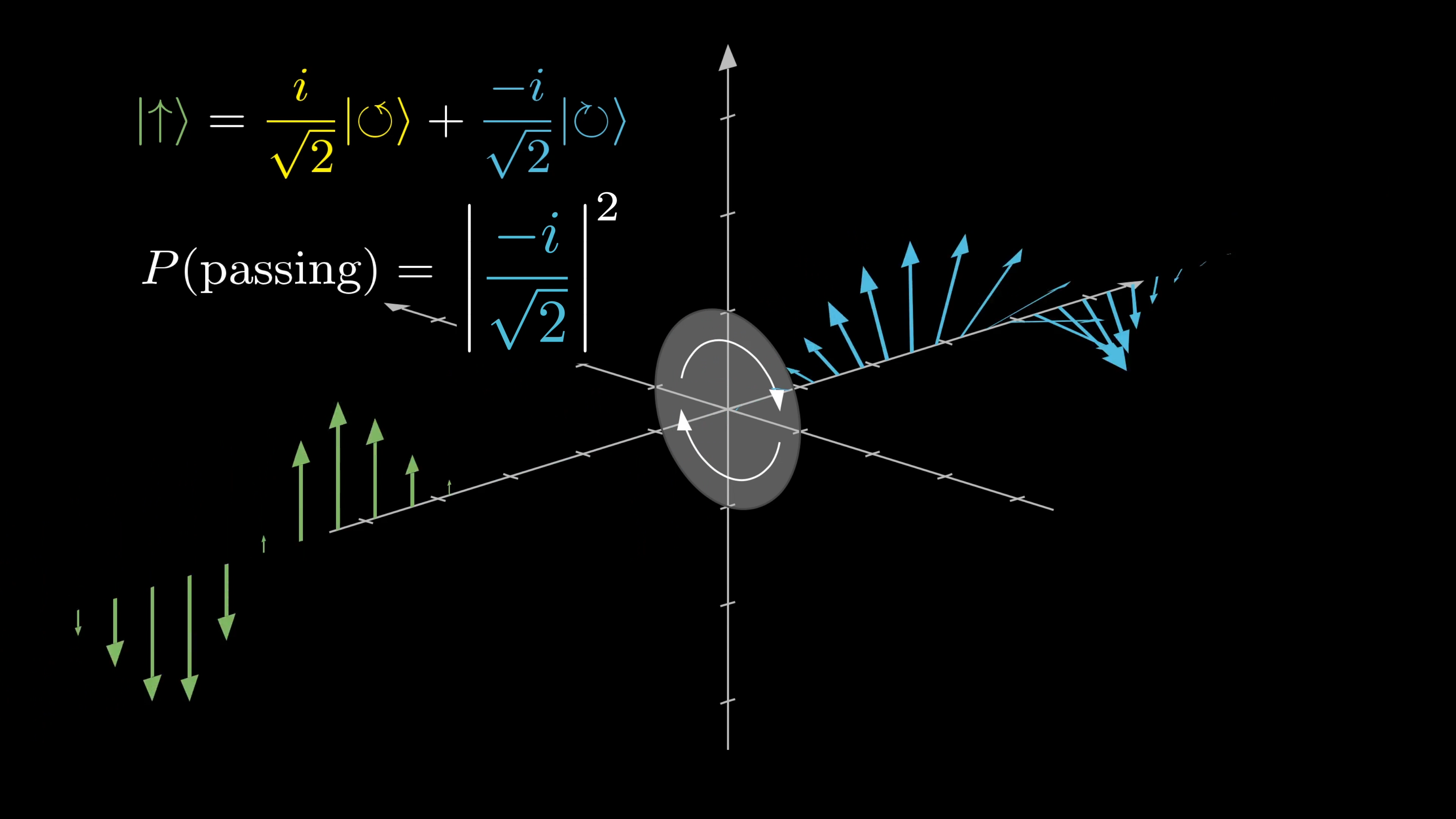

The components can still have some phase difference. Just like with classical waves, photons can be circularly polarized, and there exist polarizing filters that only let through photons polarized circularly in a rotational direction.

Or rather, they let through all photons probabilistically, where the probabilities are determined by describing each photon as a superposition of clockwise and counterclockwise states, and the square of the amplitude of the counterclockwise component gives you the desired probability.

Generalizing Quantum Phenomena

Photons are of course just one quantum phenomenon. One where we initially understood it as a wave thanks to Maxwell’s equations, and then it became quantized, hence the name quantum mechanics.

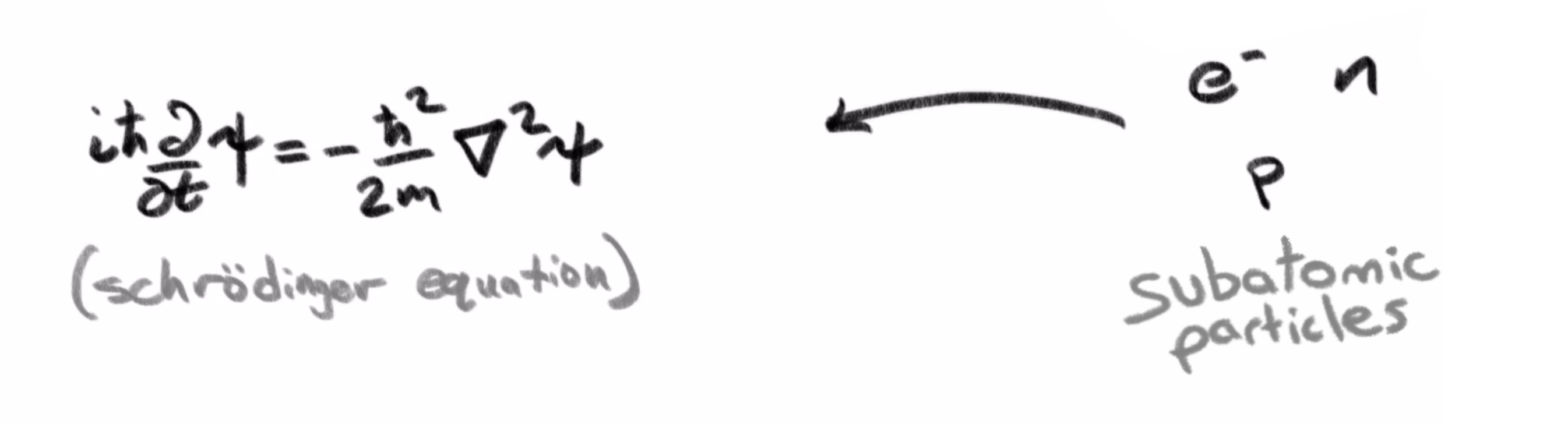

But as many of you well know, there is a flipside to this, where many things that were understood to come in discrete little packets, like electrons, were discovered to be governed by similar wave mechanics.

In cases way more general than this one photon-polarization example, quantum mechanical states are described as some superposition of multiple base states, depending on what basis you choose. Each component in this superposition is given with an amplitude and phase, often encoded as a single complex number, and the need for this phase arises from the wave nature of these objects.

As with the photon example, the choice of how to measure these objects can determine a set of base states, where the probability of measuring a particle to be in one of these base states is proportional to the squares of the amplitudes of these numbers.

It’s funny to think that if the wave nature of electrons and other particles was discovered first, we might instead refer to the whole subject as “harmonic mechanics.” Since the weirdness there is not that things come as discrete units, but that they are governed by wave equations.

Light was previously understood to be a classical wave, but that model fails to explain how the resulting waves from a filter appear to either retain all of their energy, or be completely blocked. By treating light as a stream of discrete photons, their probabilistic behavior gives a bit of insight to other quantum systems. For additional physics resources, check out the channel MinutePhysics which collaborated on this project.