But why is a sphere's surface area four times its shadow?

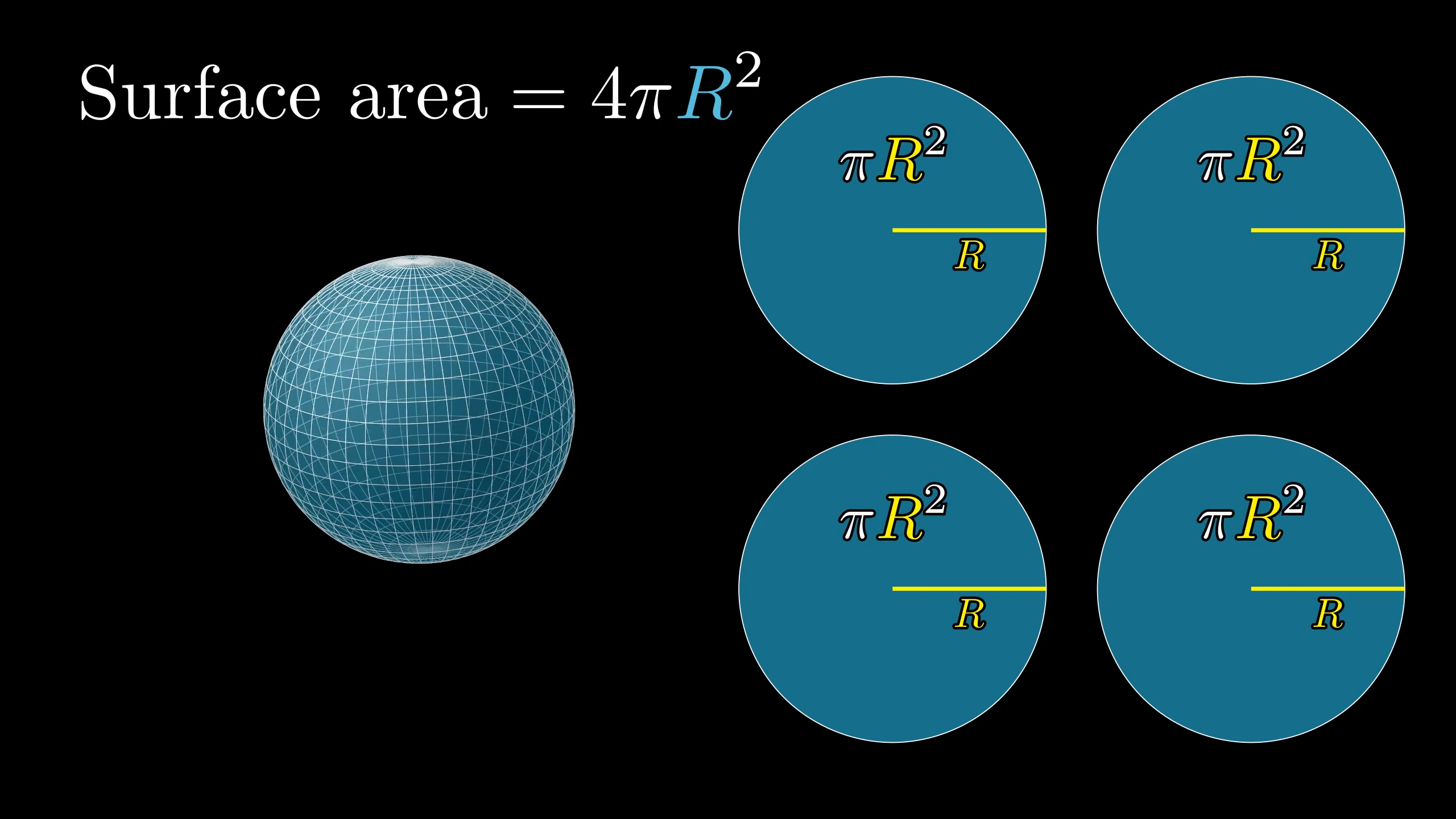

Some of you may have seen in school that the surface area of a sphere is , a suspiciously suggestive formula given that it’s a clean multiple of , the area of a circle with the same radius.

But have you ever wondered why is this true? And I don’t just mean proving this formula. I mean feeling, viscerally, a connection between the sphere's surface area, and those four circles.

But why?!?

How lovely would it be if there was some shift in perspective that showed how you could nicely and perfectly fit those four circles onto the sphere’s surface?

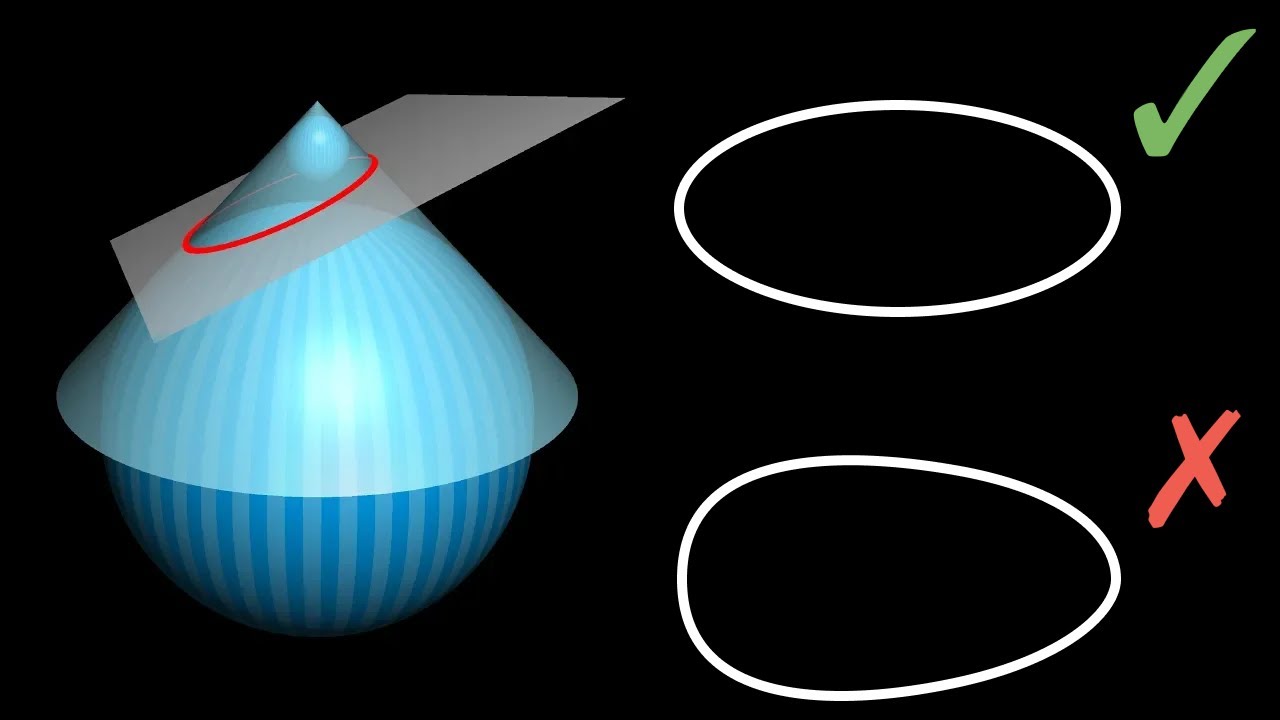

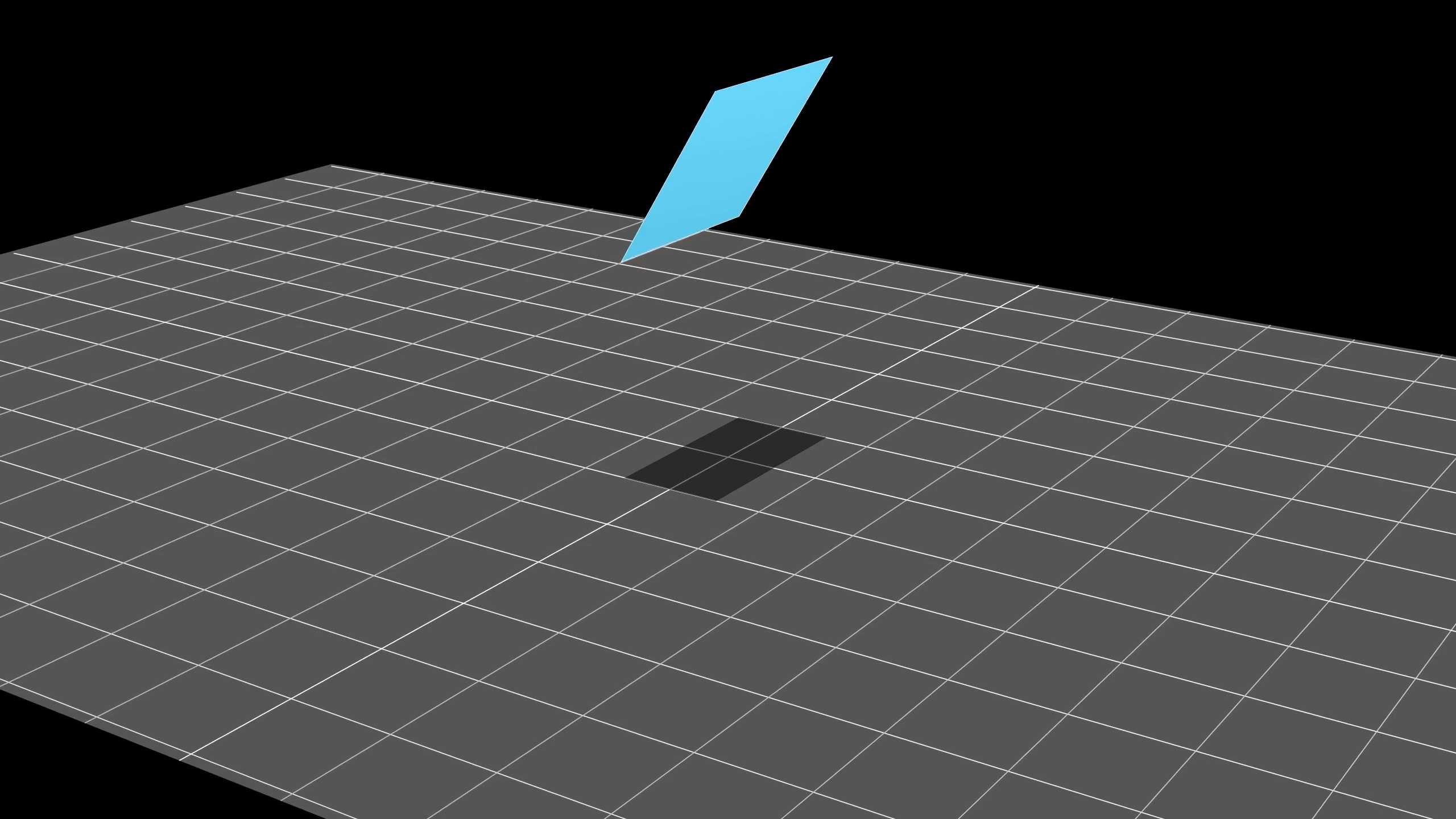

Nothing can be quite that simple, since the curvature of a sphere’s surface is different from the curvature of a flat plane, which is why trying to fit paper around a sphere doesn’t really work.

Good luck.

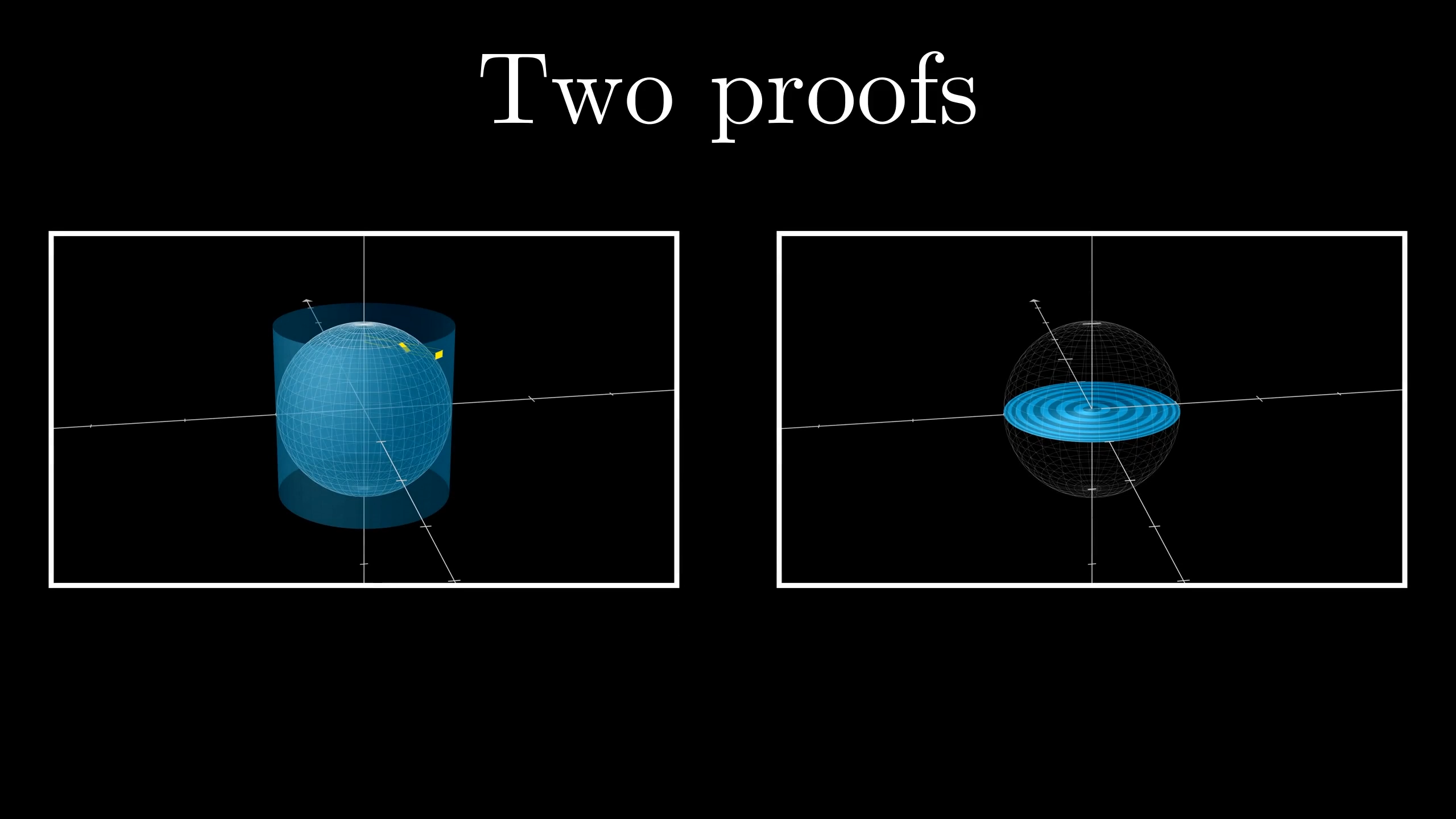

Nevertheless, I’d like to show you two ways of thinking about the surface area of a sphere which connect it in a satisfying way to four circles of the same radius.

The first is a classic. It's one of the true gems of geometry that all students should experience.

The second line of reasoning is something of my own which draws a more direct line between the sphere and its shadow.

And lastly I’ll share why this four-fold relation is not unique to spheres, but is instead one specific instance of a much more general fact for all convex shapes in 3D.

First approach

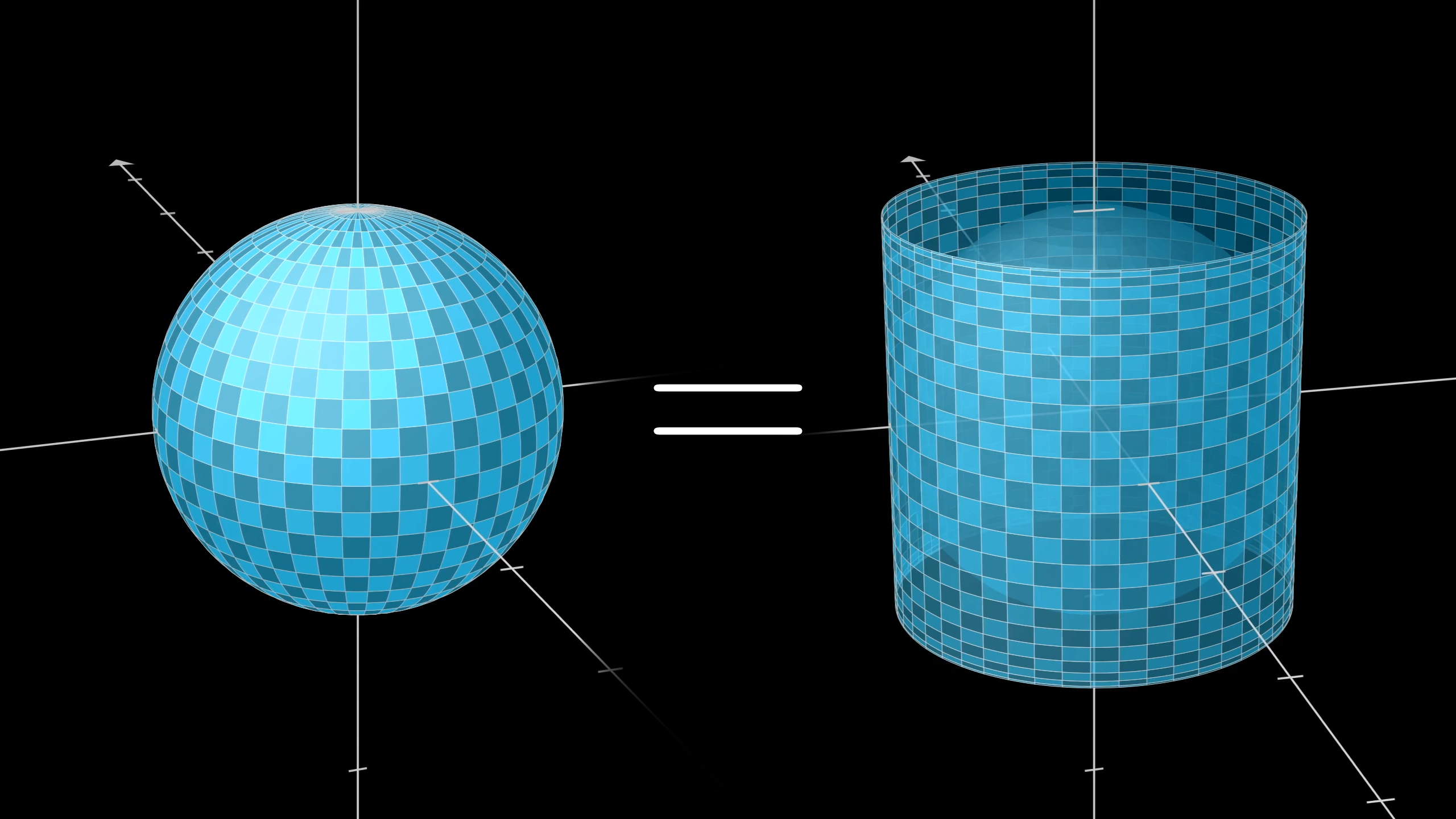

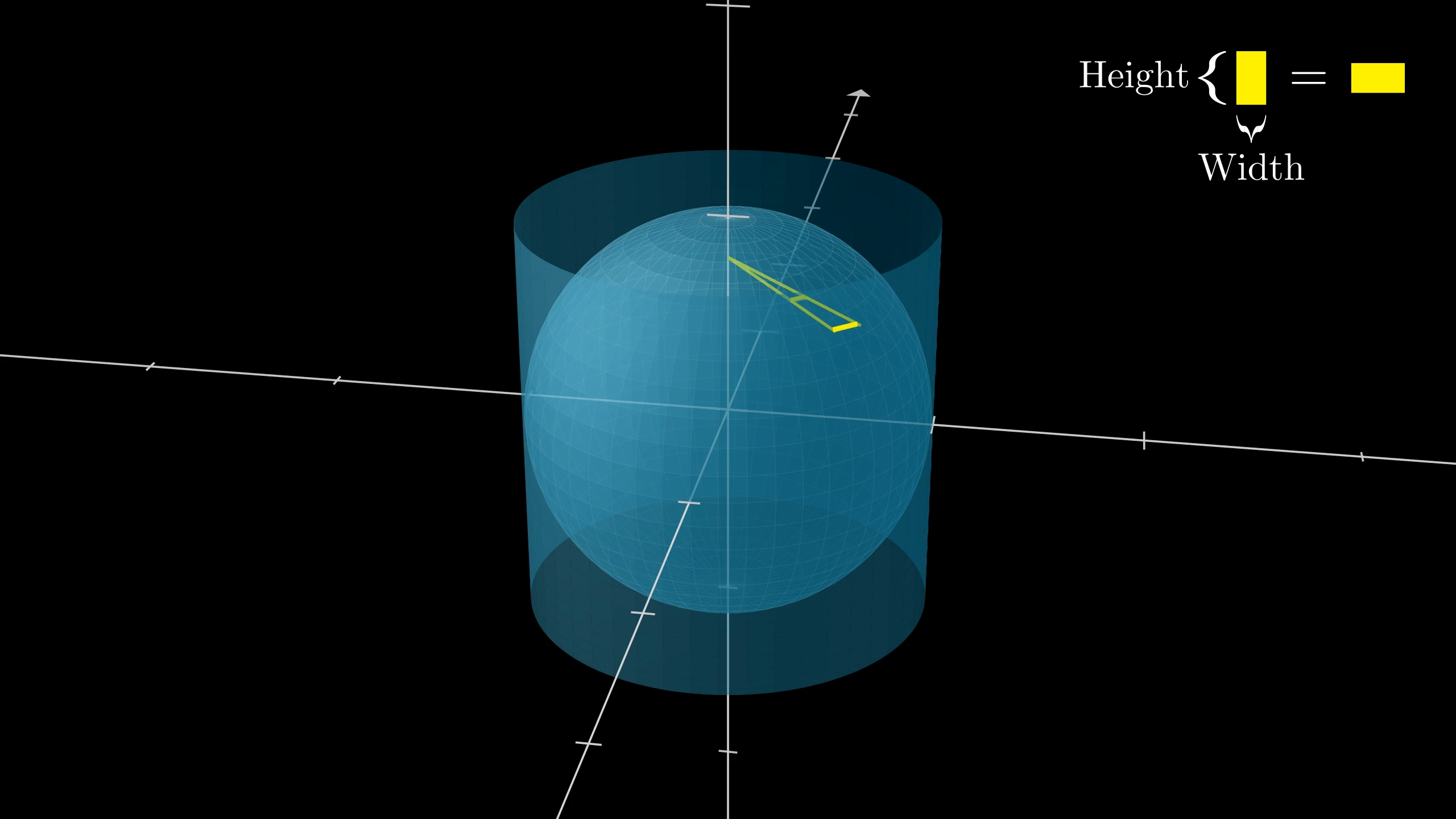

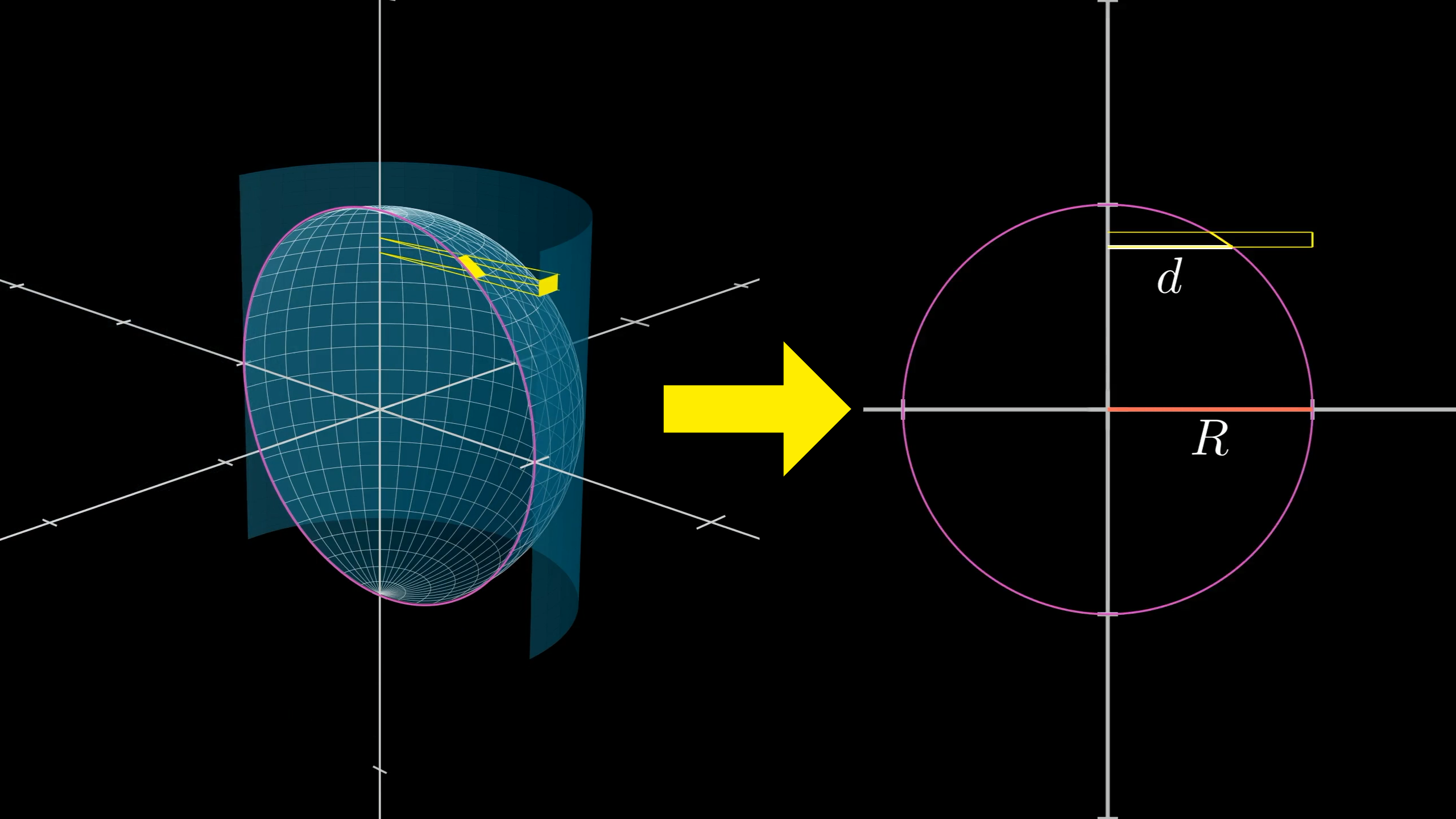

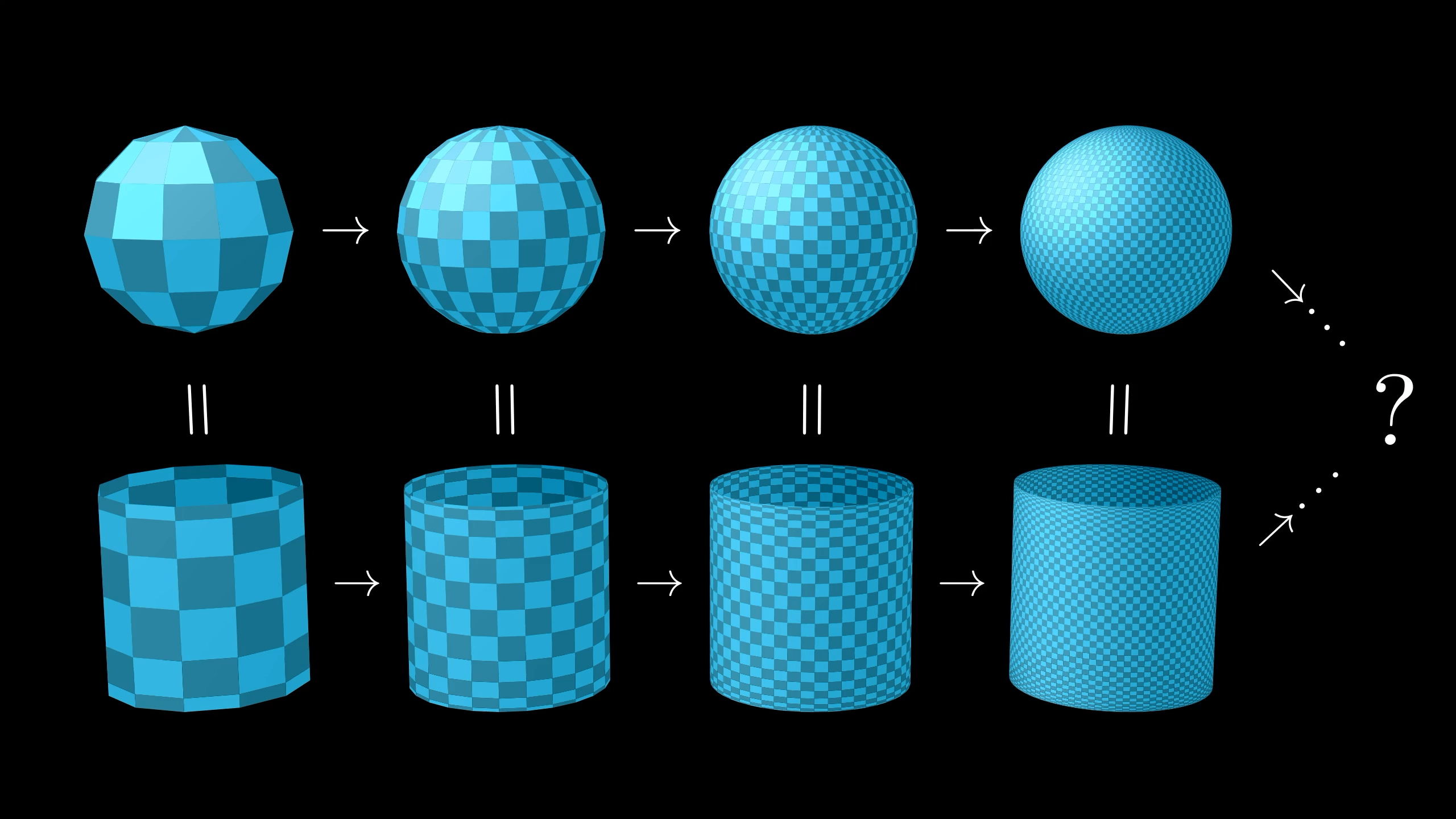

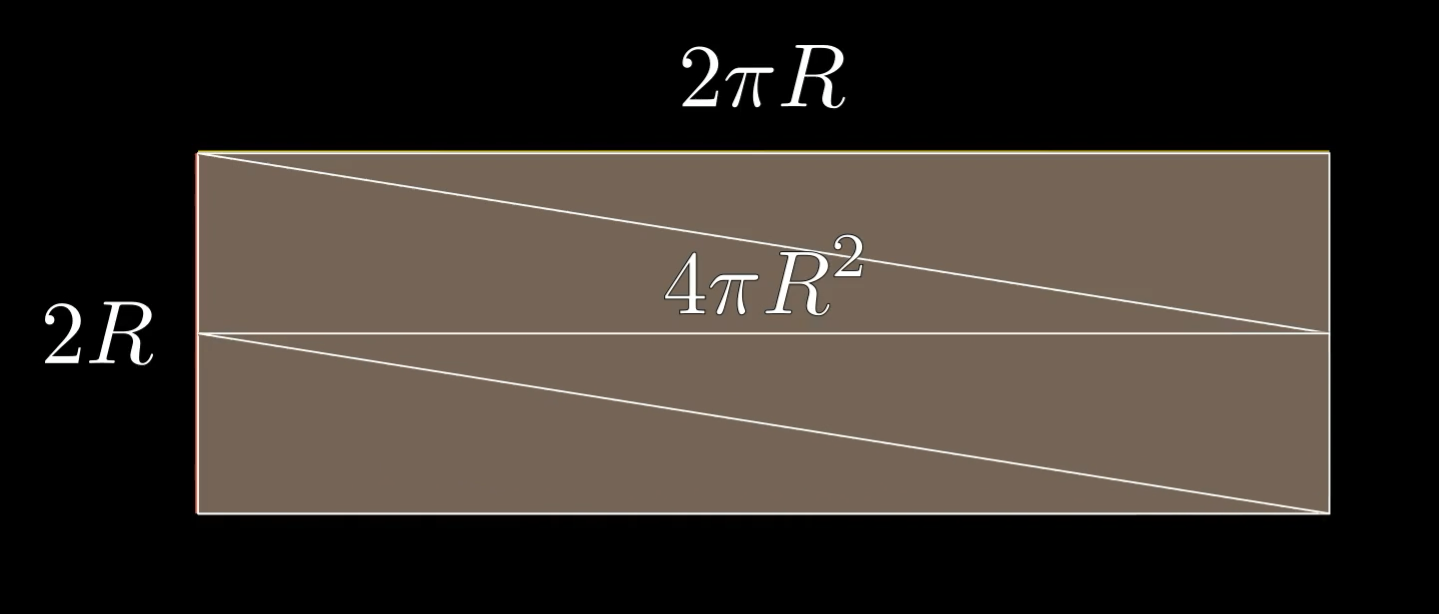

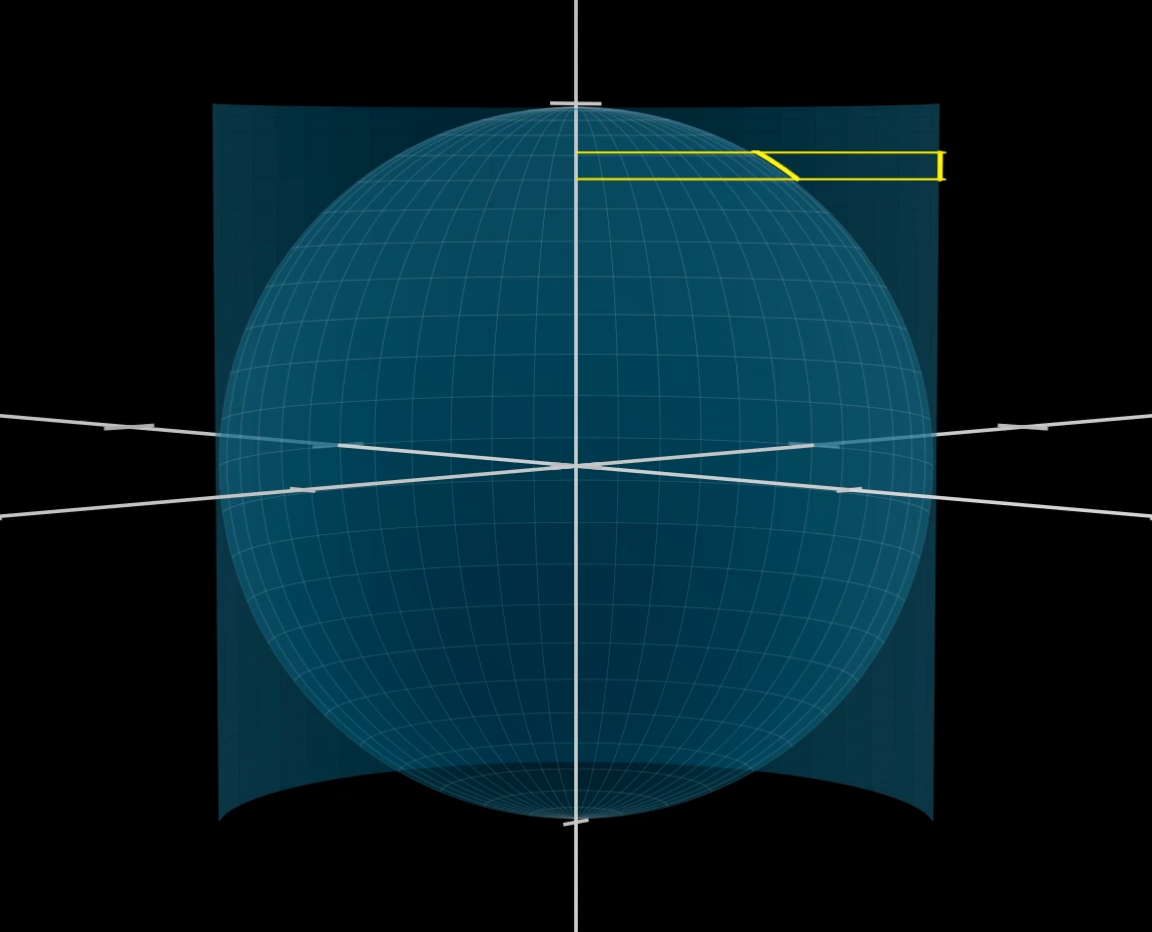

Starting with a bird's eye view here, the idea for the first approach is to show that the surface area of the sphere is the same as the area of a cylinder with the same radius and the same height as the sphere.

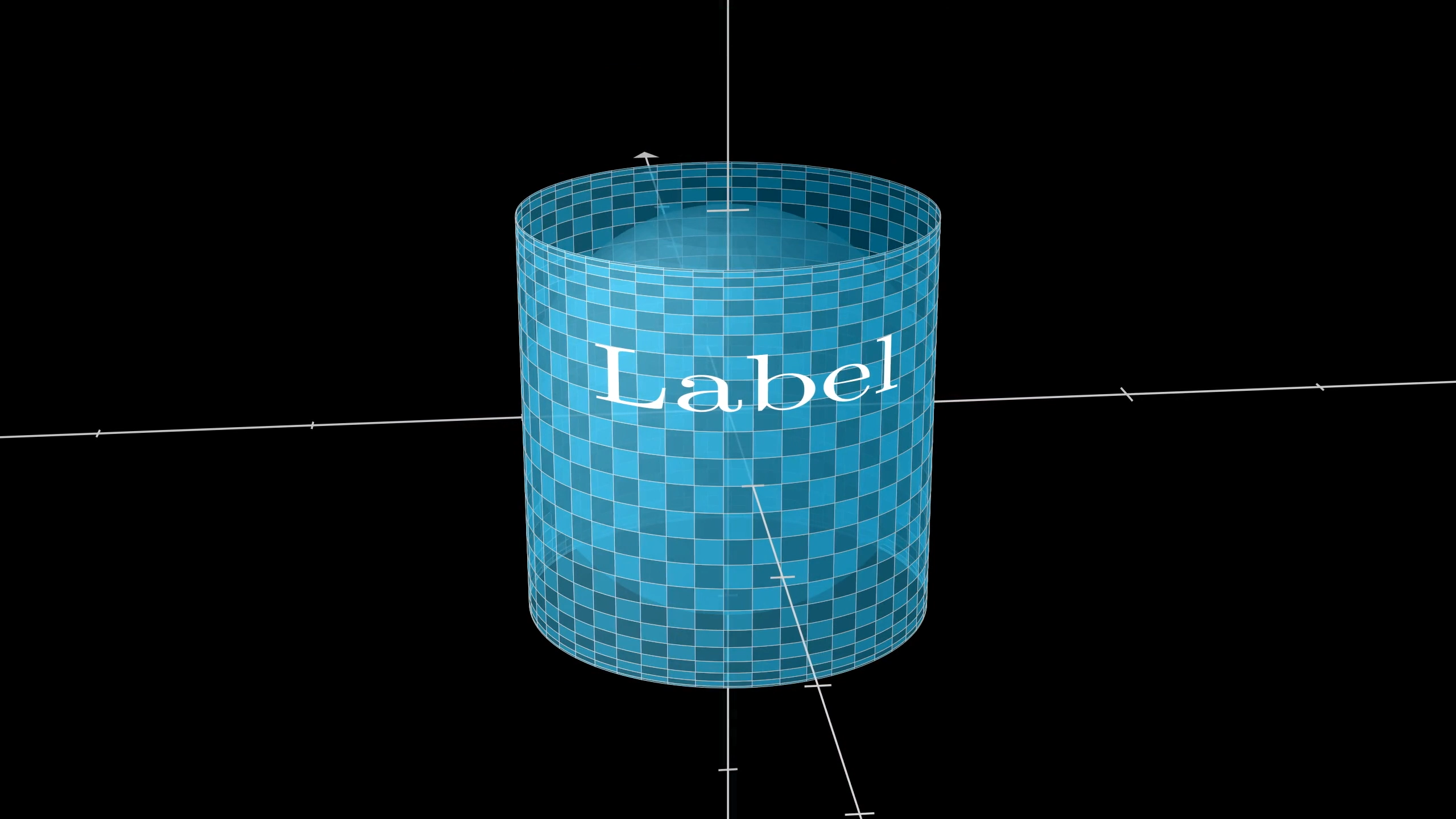

Or, rather, a cylinder without its top and bottom, which you might call the “label” of that cylinder.

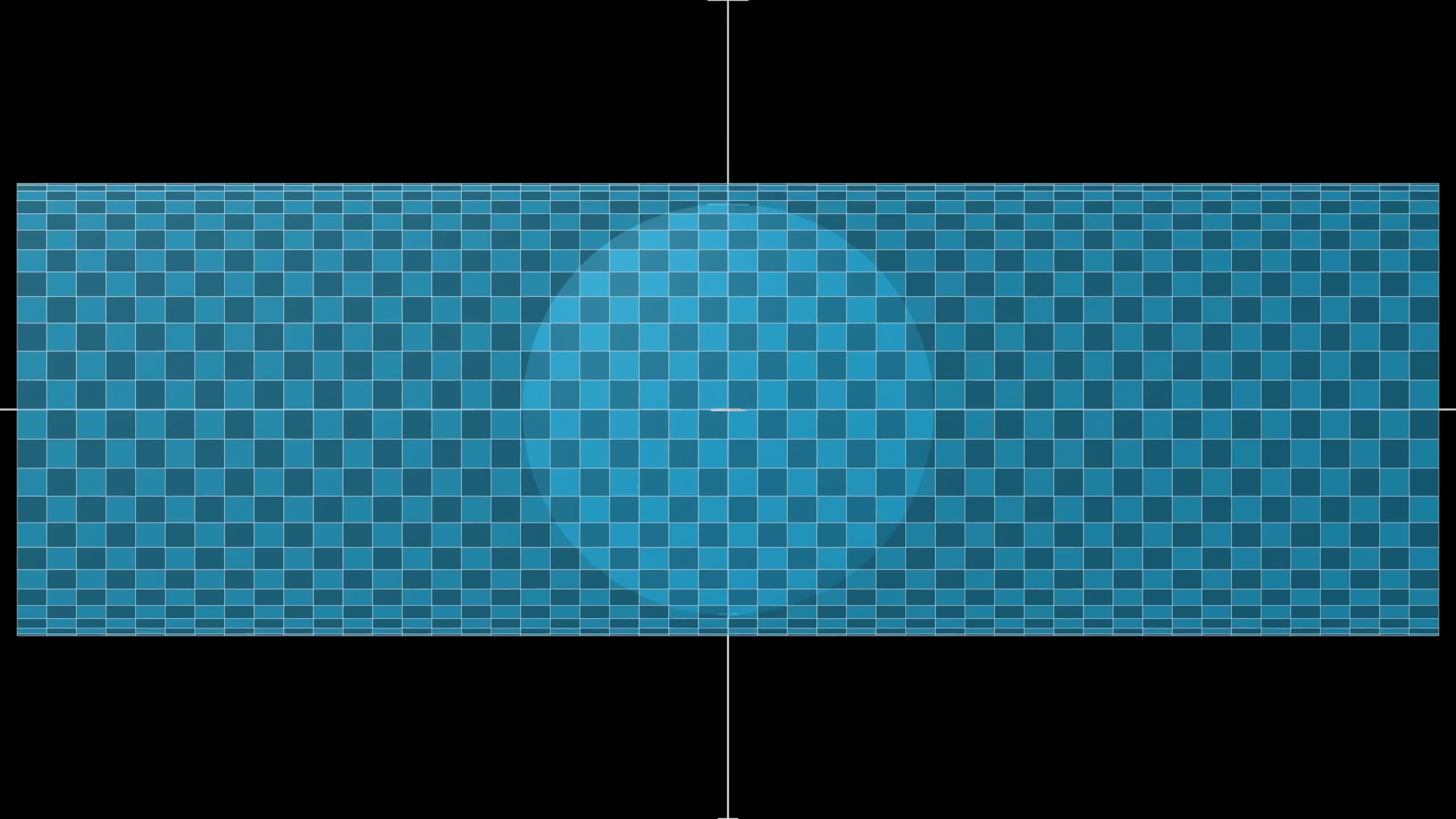

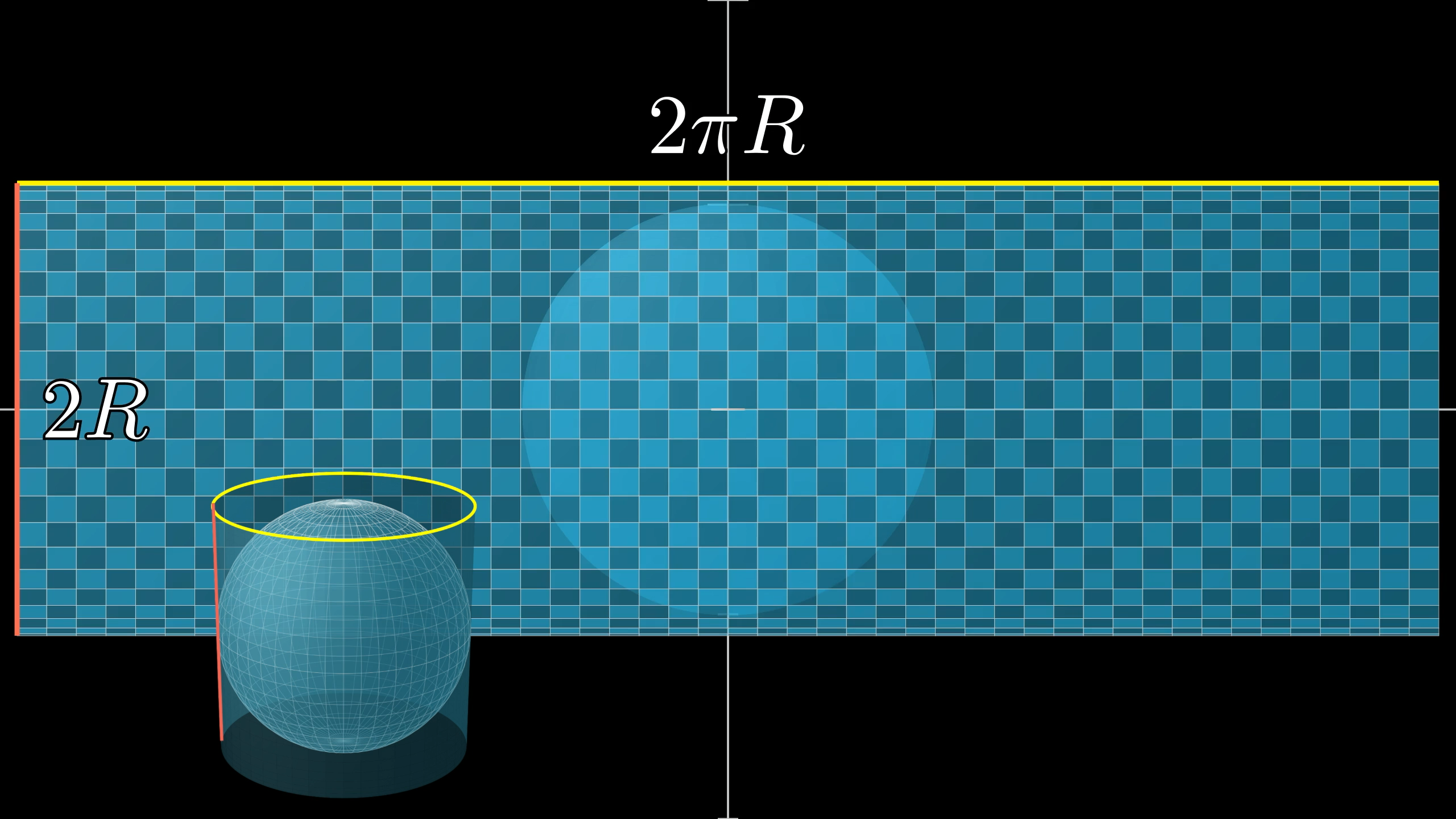

We can unwrap the label to see that it is in fact a simple rectangle.

The width of this rectangle comes from the cylinder’s circumference, , and the height comes from the height of the sphere, which is . Multiplying these already gives the formula .

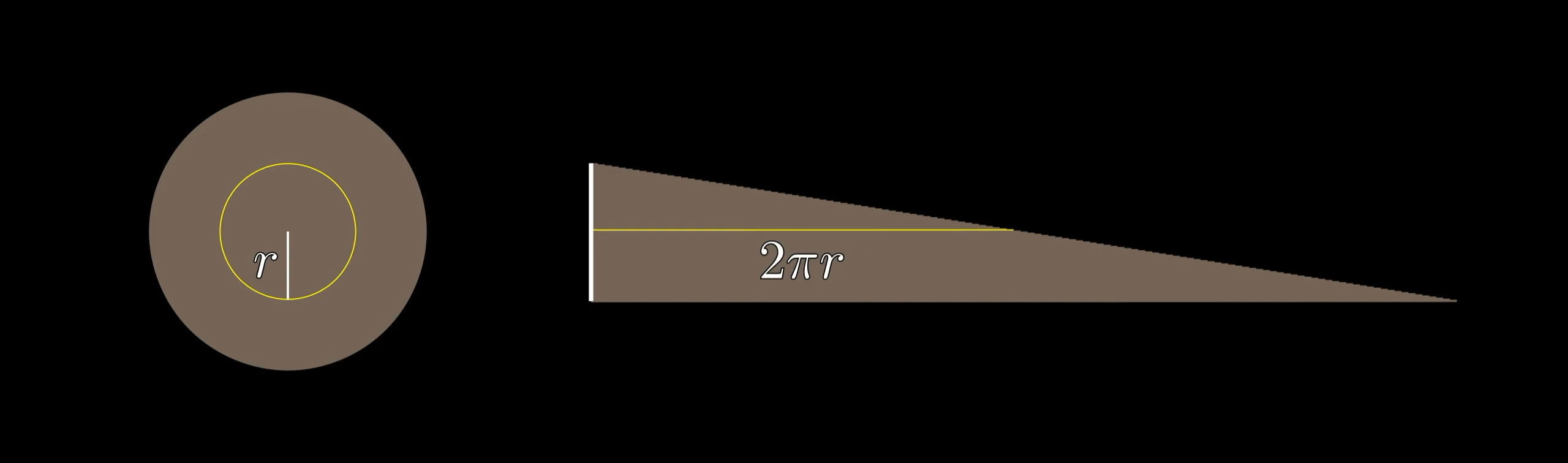

But in the spirit of mathematical playfulness, it’s nice to see how four circles with radius fit into this. The idea is that you can unwrap each circle into a triangle, without changing its area, and fit these nicely onto our unfolded cylinder label. More on that in a bit.

The more pressing question is why on earth the sphere can be related to the cylinder. This animation is already suggestive of how it works:

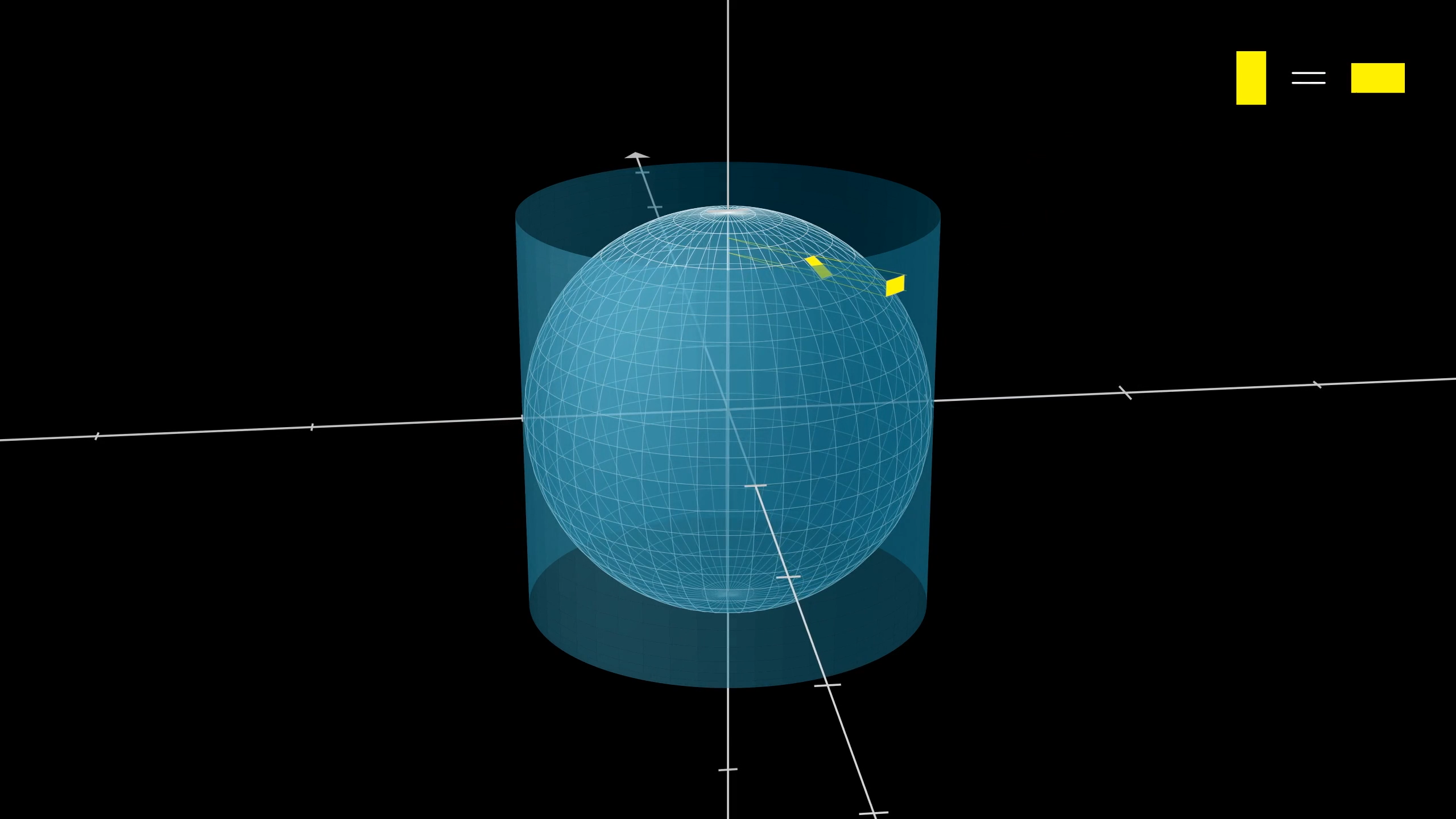

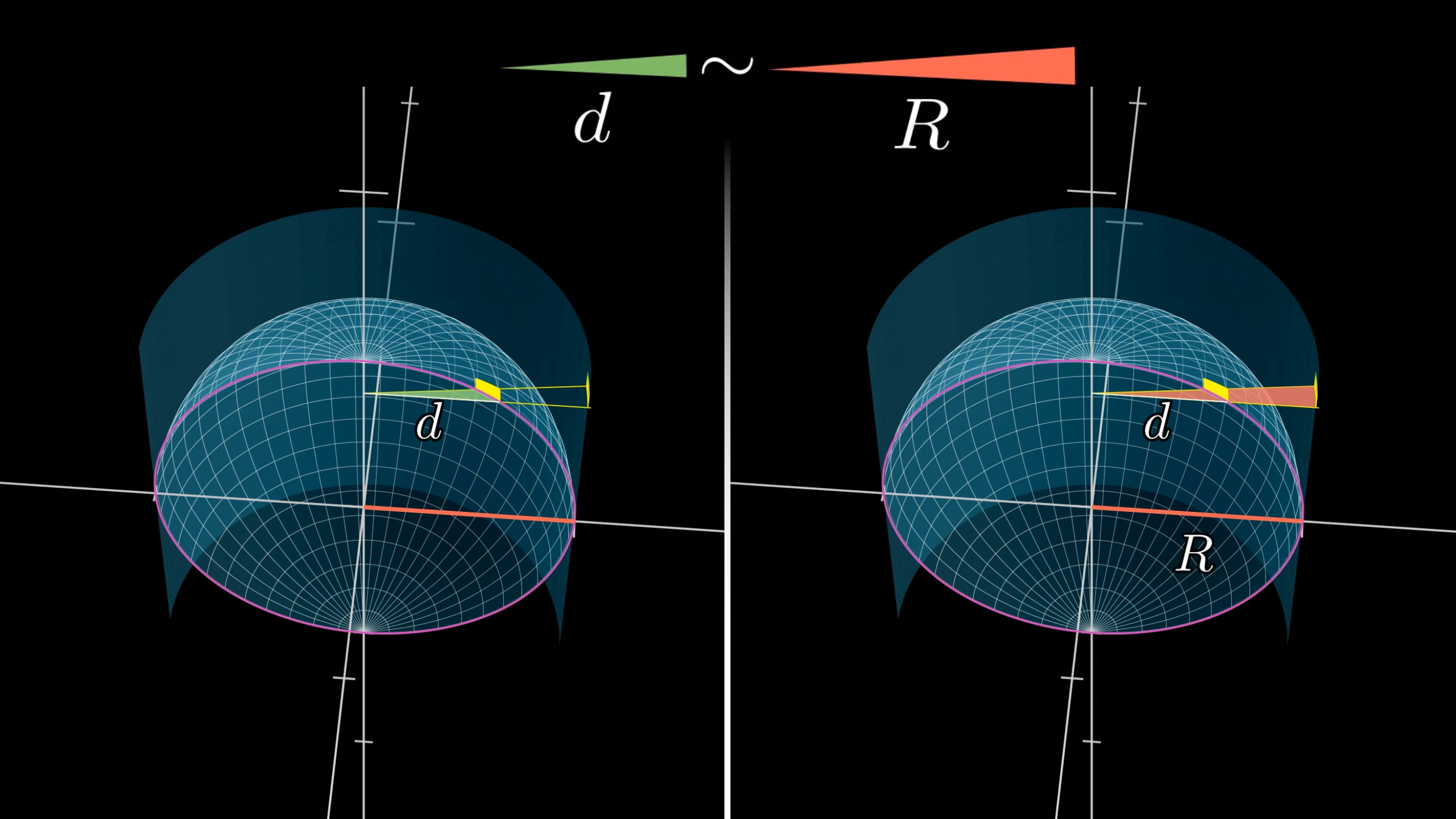

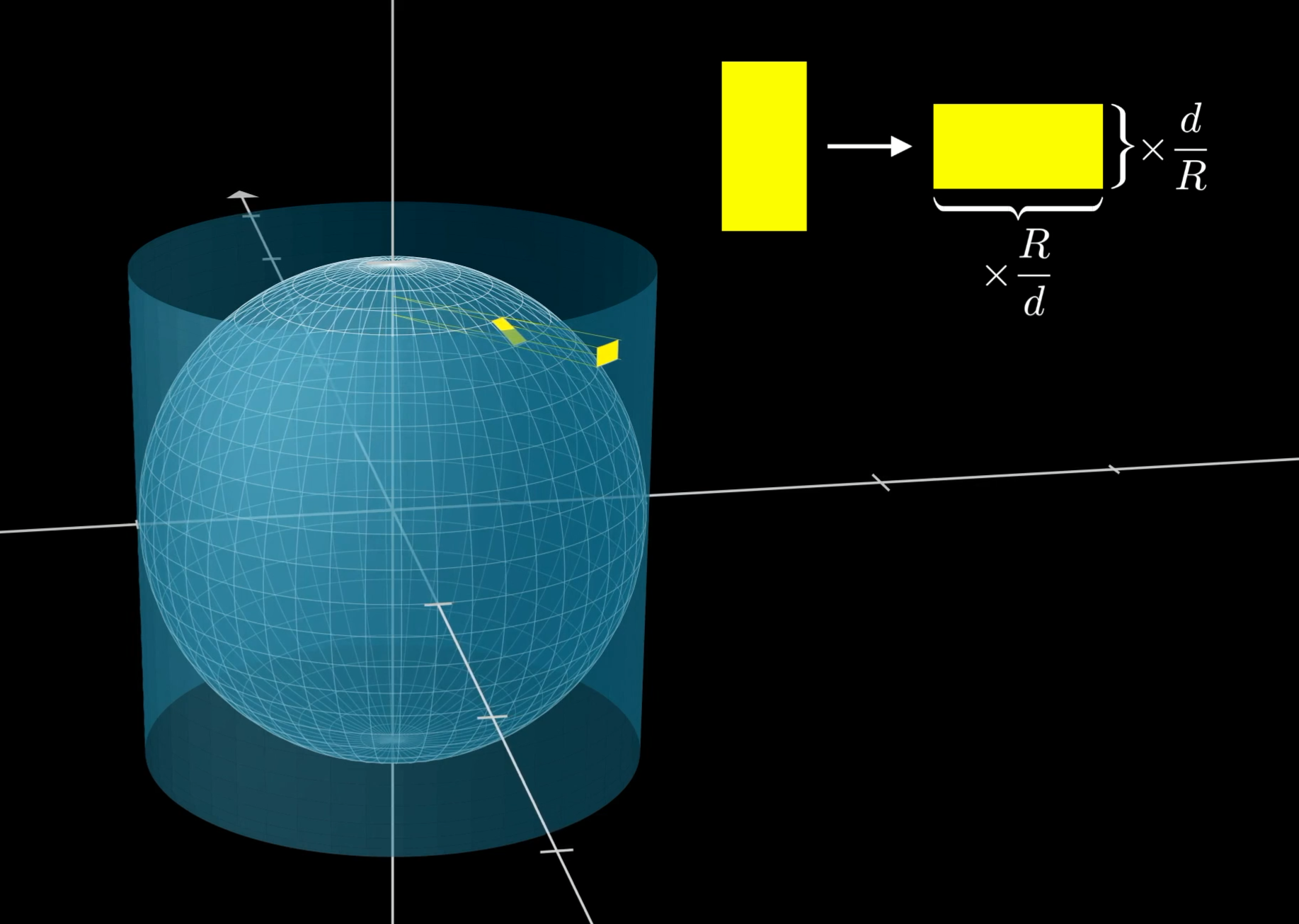

The idea is to approximate the area of the sphere with many tiny rectangles covering it. We will show that if you project those little rectangles directly outward, as if casting a shadow from little lights positioned on the z-axis, the projection of each rectangle onto the cylinder ends up having the same area as the original rectangle.

Each little rectangle on the sphere has the same area as its projection on the cylinder.

But why should that be? Well, there are two competing effects at play here. On the one hand, as this rectangle is projected outward, its width will get scaled up.

The projected rectangle is wider than the original.

For rectangles towards the poles, that width is scaled quite a bit, since they’re projected over a longer distance. For those closer to the equator, less so.

The width difference is more extreme at the poles.

But on the other hand, because these rectangles are at a slant with respect to the z-direction, during this projection the height of each such rectangle will get scaled down. Think about holding some flat object and looking at its shadow. As you reorient that object, the shadow looks more or less squished for some angles.

Those rectangles towards the poles are quite slanted in this way, so their height gets squished a lot. For those closer to the equator, less so.

The height difference is also more extreme at the poles.

It will turn out that these two effects, of stretching the width and squishing the height, cancel each other out perfectly.

As a rough sketch, wouldn’t you agree that this is a very pretty way of reasoning? Of course, the meat here comes from showing why these two competing effects on each rectangle cancel out perfectly. In some ways, the details fleshing this out are just as pretty as the zoomed out structure of the full argument.

Stretching the width

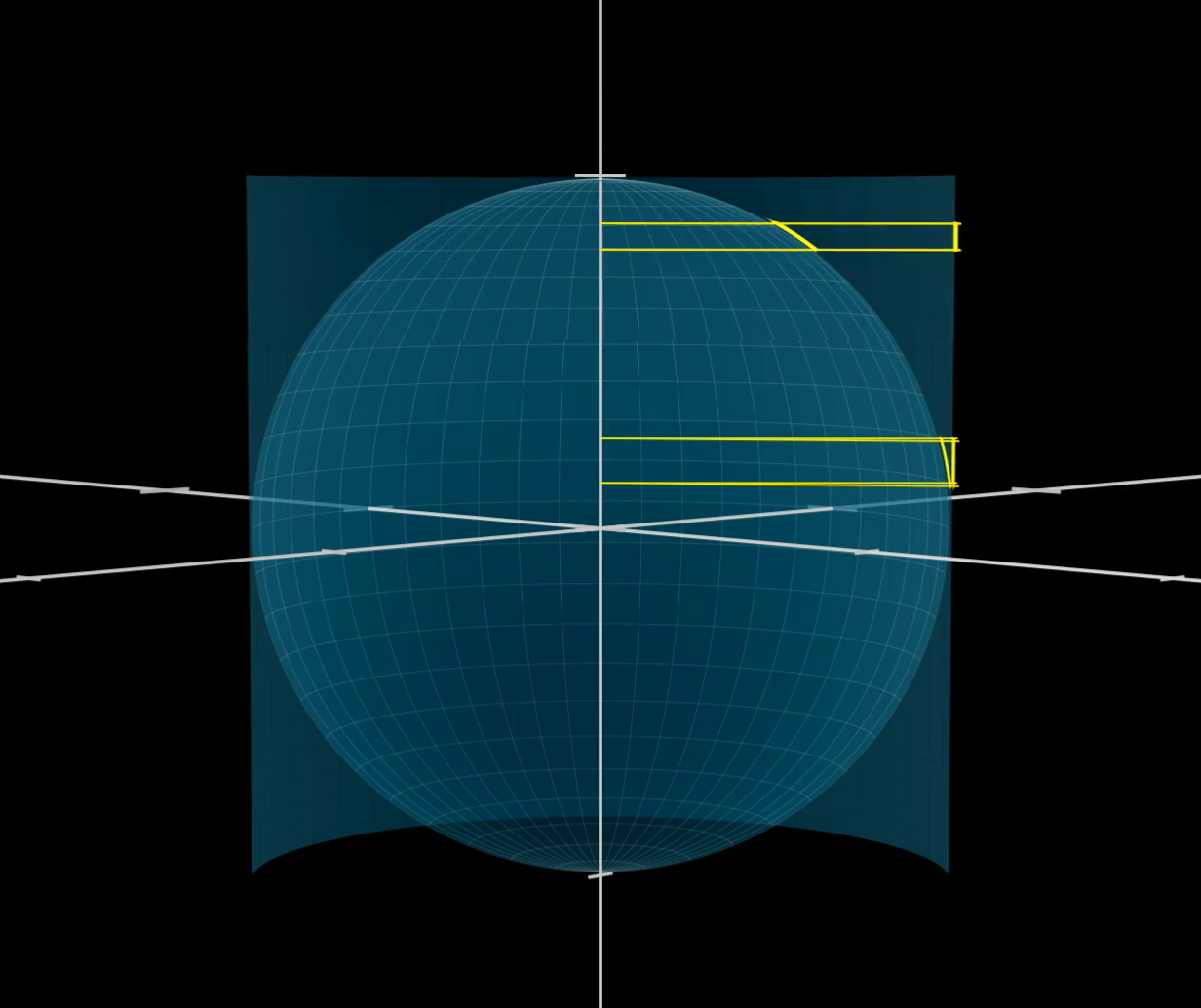

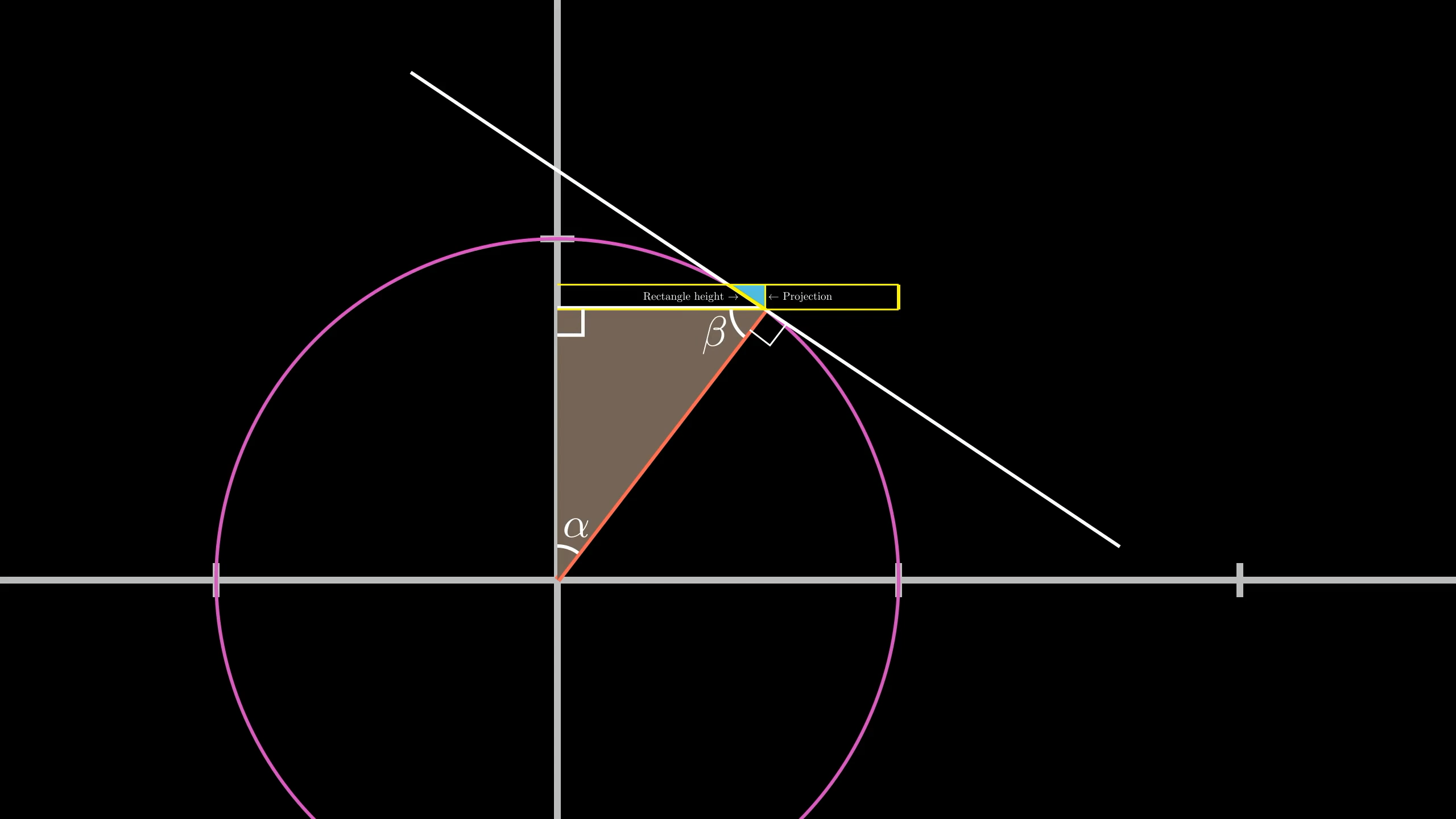

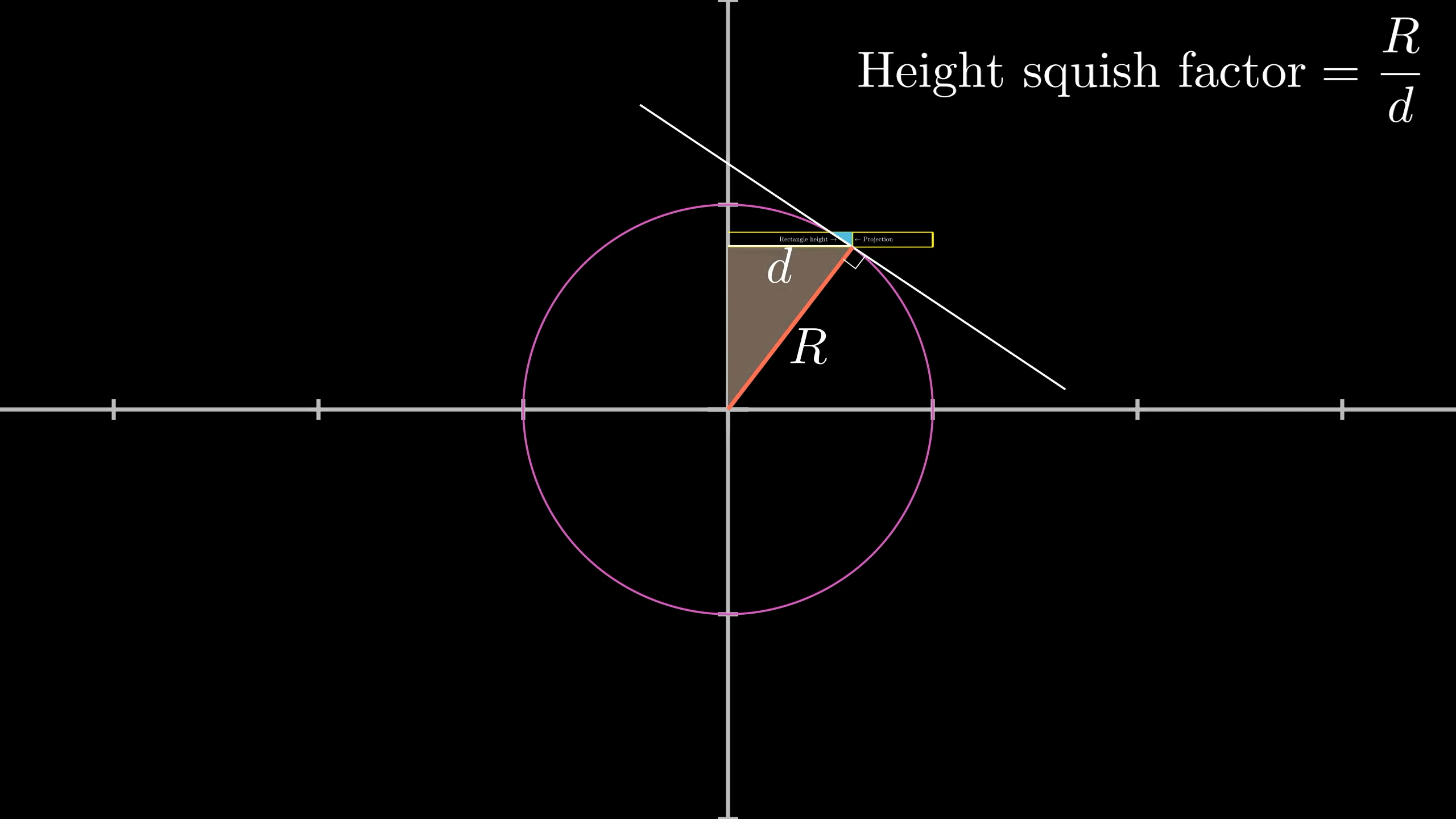

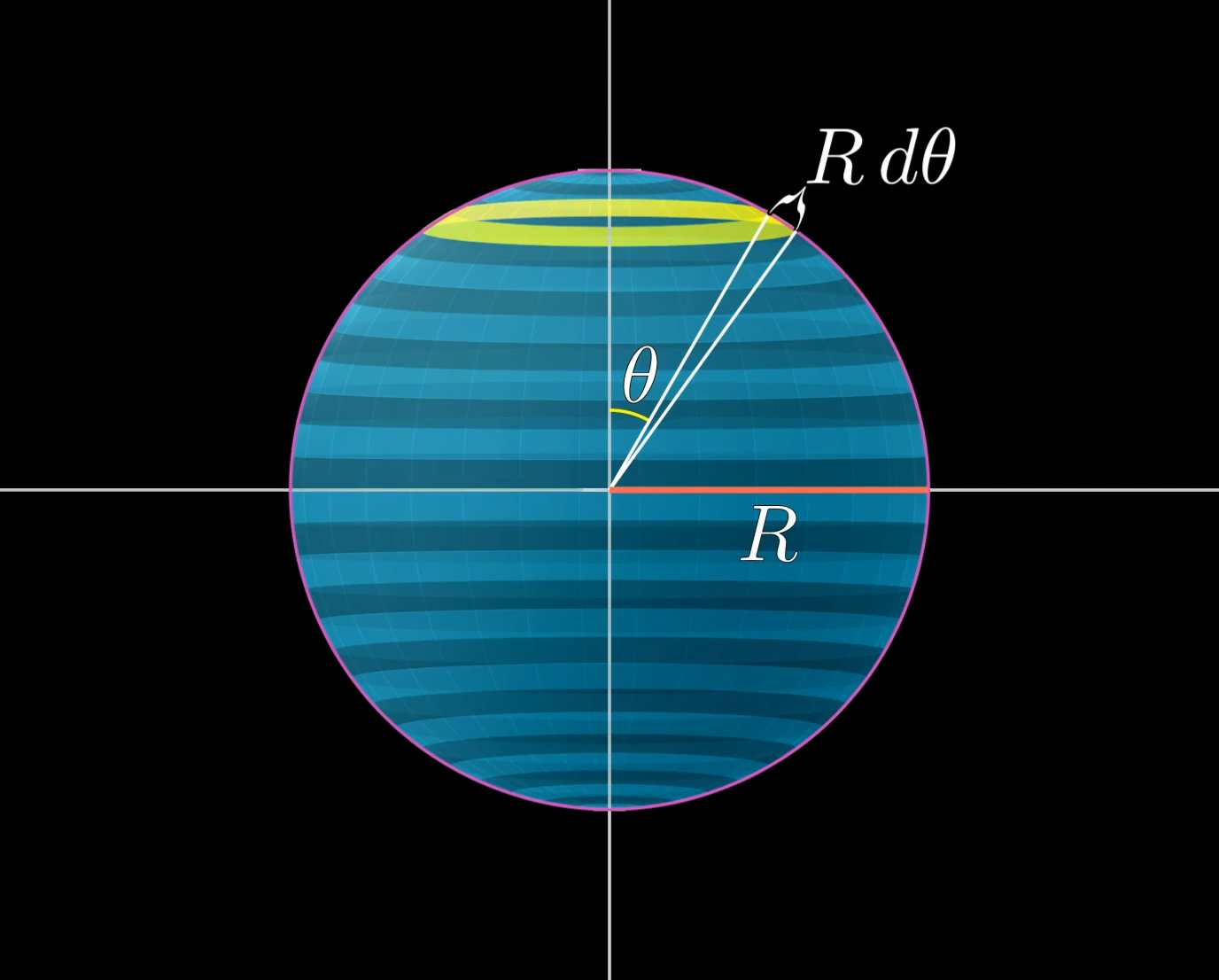

For any mathematical problem-solving it never hurts to start by giving names to things. Let’s say the radius of the sphere is . Also, focusing on one specific rectangle, let’s call the distance between our rectangle and the z-axis .

This cross-section of the sphere shows how we're choosing to label things.

You could rightfully complain that this distance is a little ambiguous depending on which point on the rectangle you’re starting from, but for tinier and tinier rectangles that ambiguity will be negligible. And tinier and tinier is precisely when this approximation with rectangles gets closer to the true surface area anyway. To choose an arbitrary standard, let’s say is the distance from the bottom of the rectangle to the z-axis.

To think about projecting out to the cylinder, picture two similar triangles.

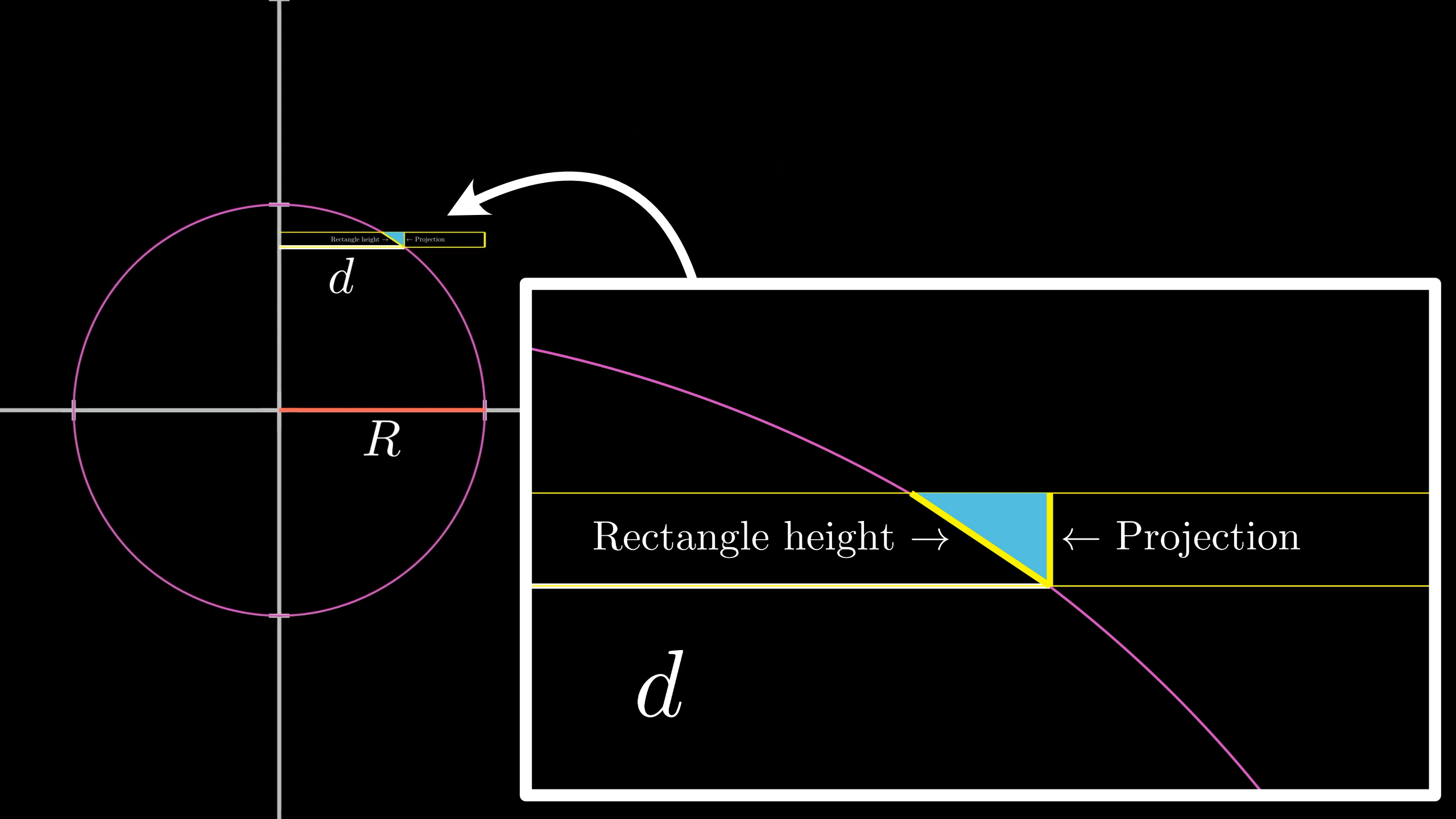

This first one shares its base with the rectangle on the sphere. The second is a scaled up version of this, scaled so that it just barely reaches the cylinder, meaning its long side now has length . So the ratio of their bases, which is how much our rectangle’s width gets stretched out, is .

Squishing the height

What about the height? How precisely does that get scaled down as we project?

To figure it out, let's begin by focusing our attention on this 2D cross section:

Then, to think about the projection, let’s zoom in and make a little right triangle like this:

Our right triangle is positioned with its hypotenuse along the original rectangle, and one of its legs along the projection of that rectangle onto the cylinder.

Pro tip: Any time you’re doing geometry with circles or spheres, keep at the forefront of your mind that anything tangent to the circle is perpendicular to the radius drawn to that point of tangency. It’s crazy how helpful that one little fact can be.

Once we draw that radial line, together with the distance , we have another right triangle.

Often in geometry, I like to imagine tweaking the parameters of a setup and imagining how the relevant shapes change; this helps to make guesses about what relations there are.

In this case, you might predict that the two triangles I’ve drawn are similar to each other, since their shapes change in concert with each other.

This is indeed true, but as always, don’t take my word for it, see if you can justify this for yourself.

Similar triangles

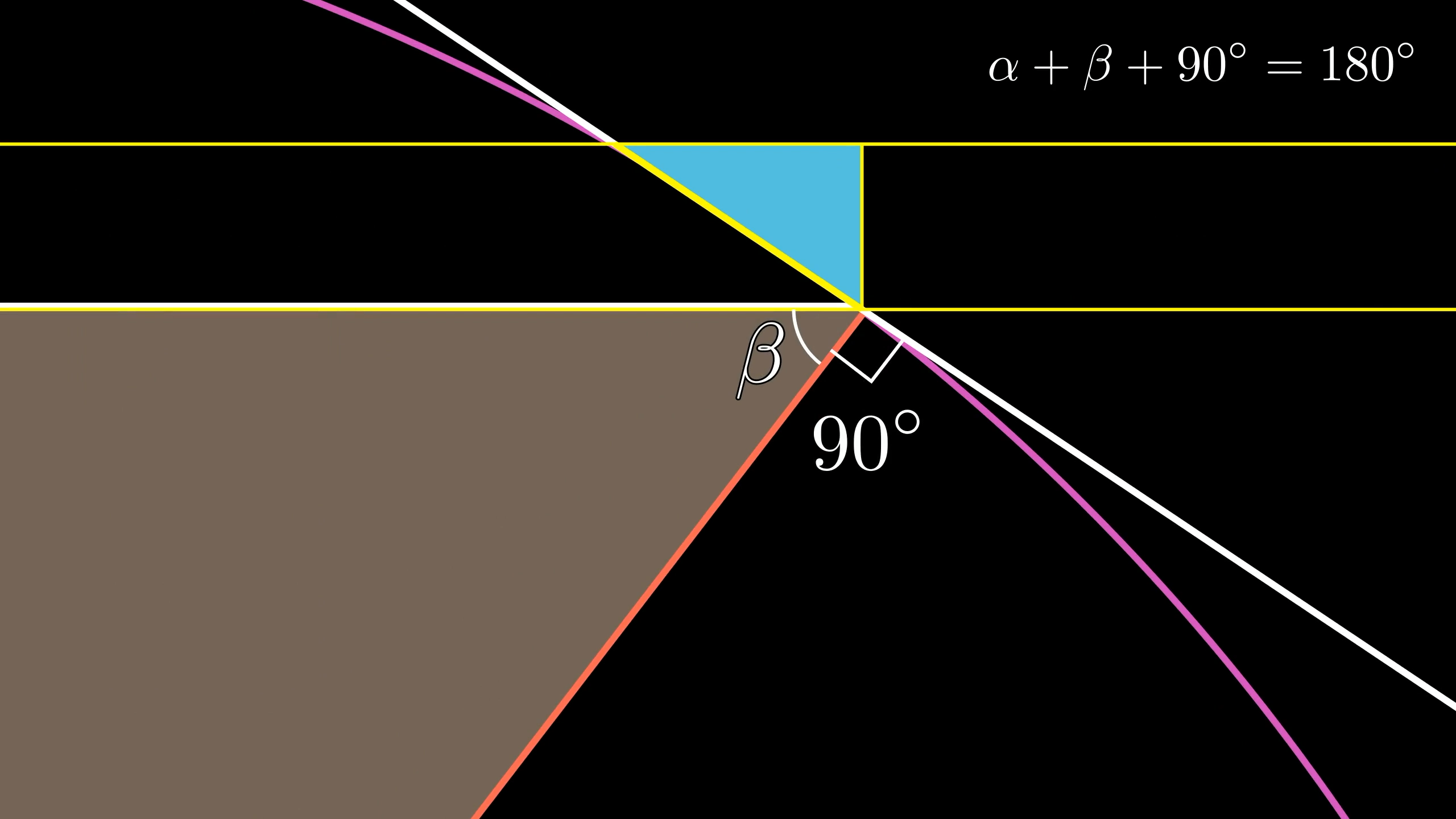

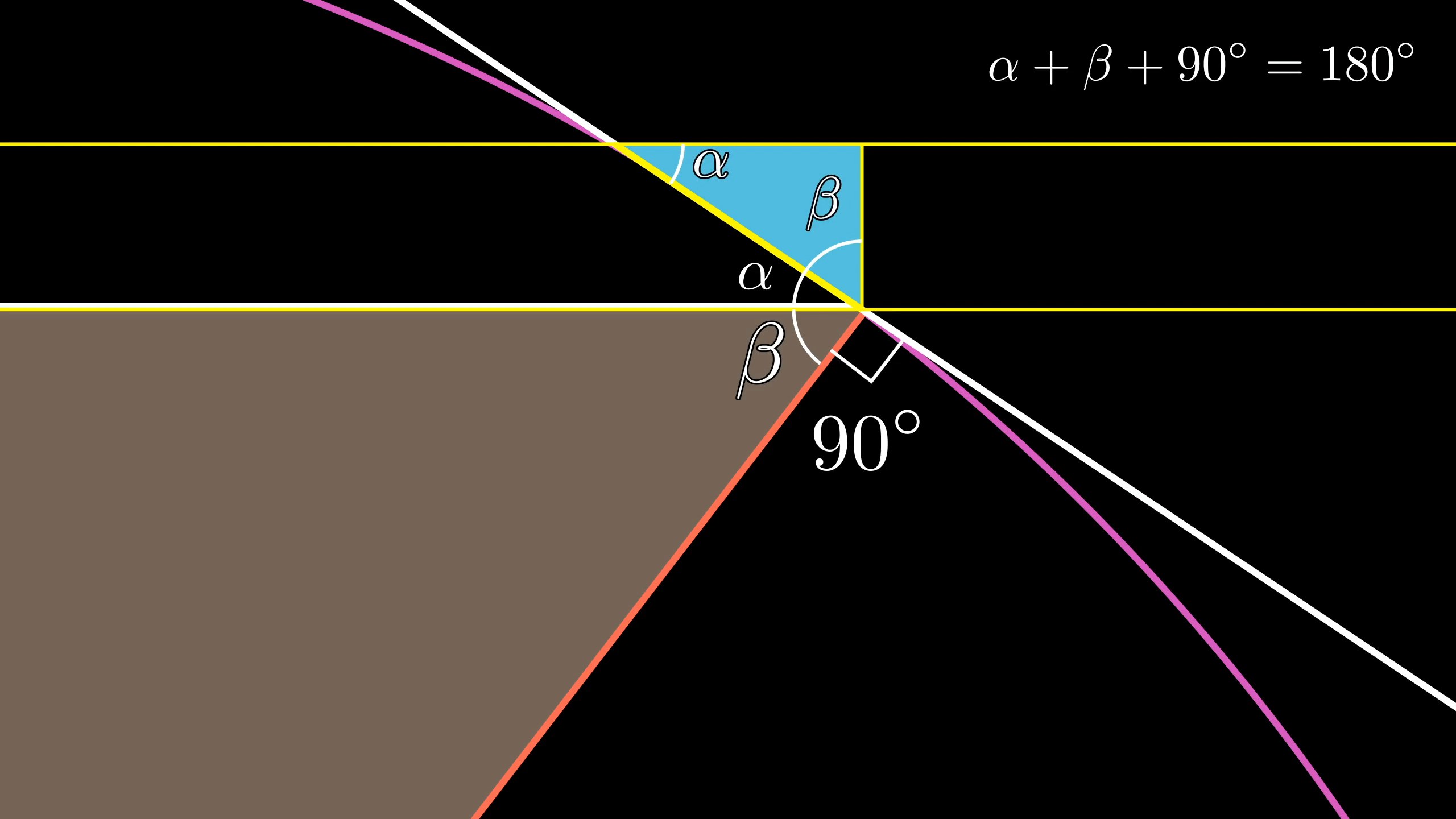

Again, it never hurts to give more names to things. Let's call these angles and :

Since this is a right triangle, you know that . Now zoom in to our little triangle, and see if we can figure out its angles:

You have forming a straight line. So that little angle must be . This lets us fill in a few more values, revealing that this little triangle has the same angles, and , as the big one.

So they are indeed similar.

Deep in the weeds, it’s sometimes easy to forget why we’re doing this. We want to know how much the height of our sphere-rectangle gets squished during the projection, which is the ratio of the hypotenuse to the leg on the right. By the similarity with the big triangle, that ratio is .

So indeed, as this rectangle gets projected outward onto the cylinder, the effect of stretching out the width is perfectly canceled out by how much the height gets squished due to the slant.

Now, if you’re really thinking critically, you might still not be satisfied that this shows that the surface area of the sphere equals the area of this cylinder label. After all, these little rectangles only approximate the relevant areas.

The idea is that this approximation gets closer and closer to the true value for finer and finer coverings. Since for any specific covering, the sphere rectangles have the same area as the cylinder rectangles, whatever values each of these two series of approximations are approaching must actually be the same.

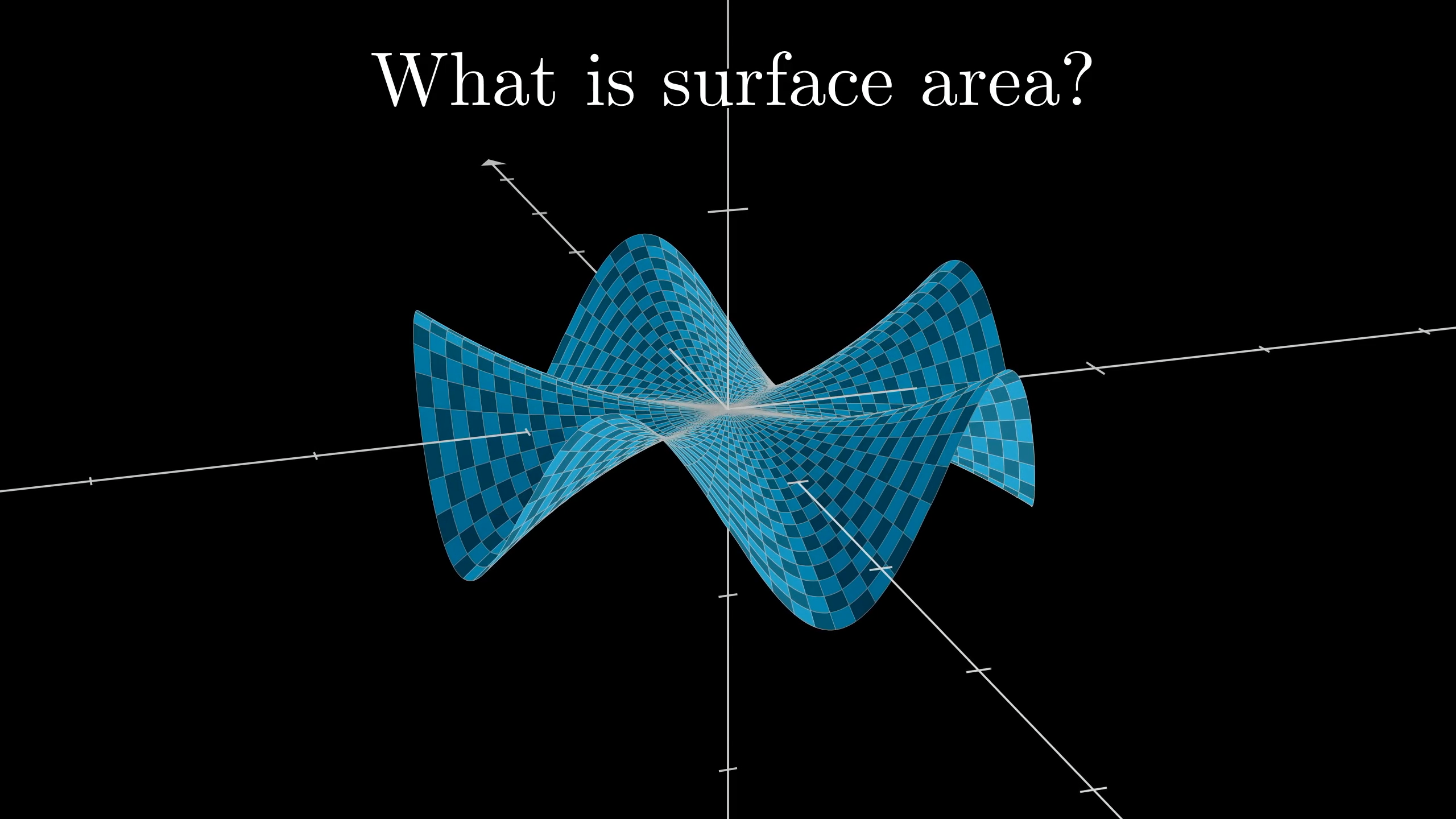

As you get more philosophical and ask what exactly we mean by surface area, these sorts of rectangular approximations and not just aids in our problem-solving toolbox, they end up serving as a way of rigorously defining the area of smooth curved surfaces, though often some care is required.

This kind of reasoning is essentially calculus, just stated without any of the jargon. In fact, I think neat geometric arguments like this, which require no background in calculus to understand, can serve as a great way to tee things up for new calculus students so that they have the core ideas before seeing the definitions which make them precise (rather than the other way around).

These geometric arguments are great preparation for understanding calculus.

Connection to circles

If you’re itching to see a direct connection to four circles, one nice way is to unwrap these circles into triangles. If this is something you haven’t seen before, I go into much more detail about why this works in the first lesson of the calculus series.

The basic idea is to relate thin concentric rings of the circle with horizontal slices of this triangle.

Each circle is unwrapped such that a thin ring of the circle corresponds to a thin line of the triangle.

Because the circumference of each such ring increases linearly in proportion to the radius, always equal to , when you unwrap them all and line them up, their ends will form a straight line (as opposed to some kind of curvey shape), giving you a triangle with a base of and a height of .

And four of these unwrapped circles fit into our rectangle, which is in some sense an unwrapped version of the sphere’s surface.

Second approach

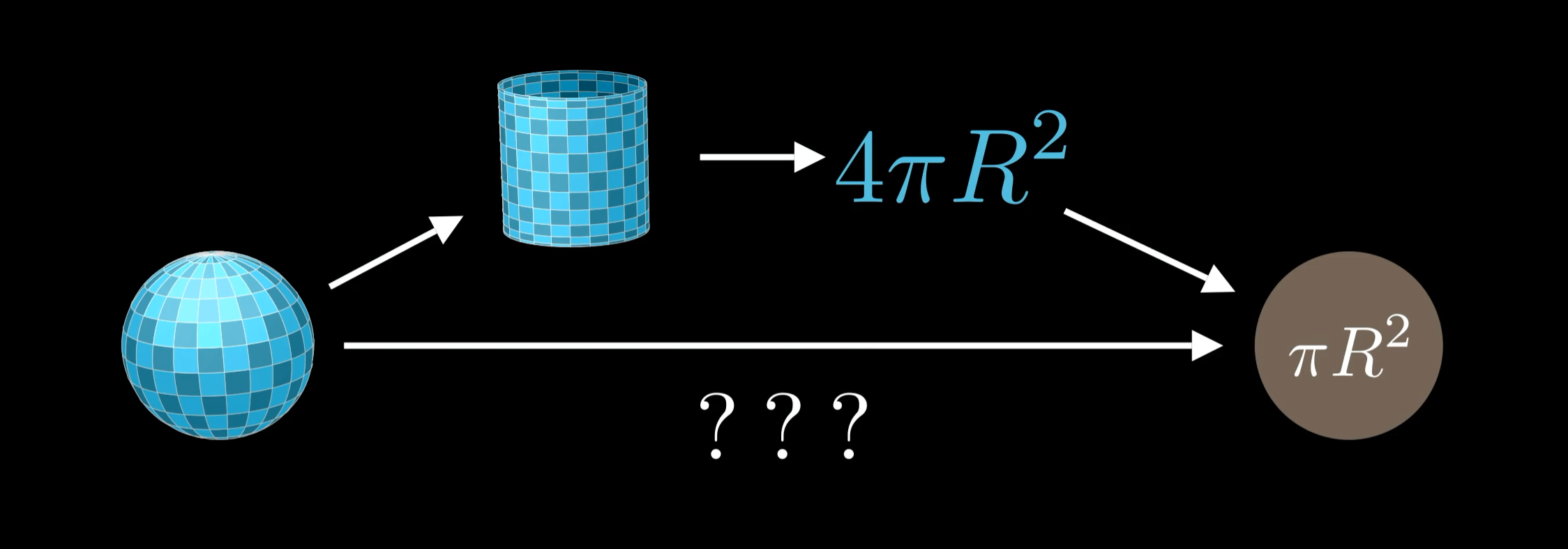

Nevertheless, you might wonder if there’s a way to relate the sphere directly to a circle with the same radius, rather than going through this intermediary of the cylinder.

If you're willing to roll up your sleeves and leverage a little trigonometry, it is actually possible to draw this more direct connection.

I’m a big believer that the best way to really learn math is to do problems yourself, which is a bit hypocritical coming from a channel essentially consisting of lectures. So let's try something a little different here and present the proof as a heavily guided sequence of exercises. Yes, I know that’s less fun and it means you have to pull out some paper to do some work, but I guarantee you’ll get more out of it this way.

Solution overview

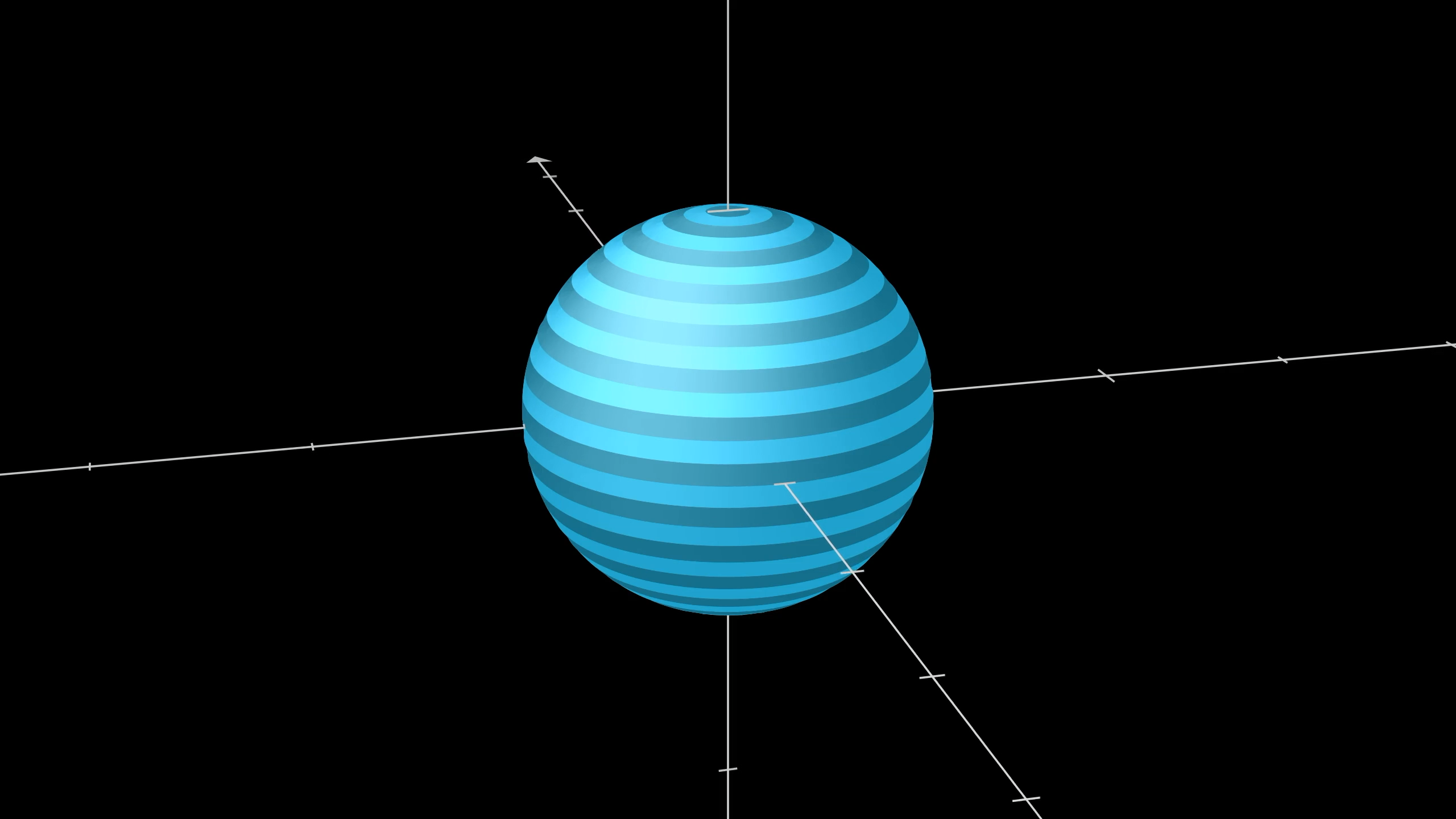

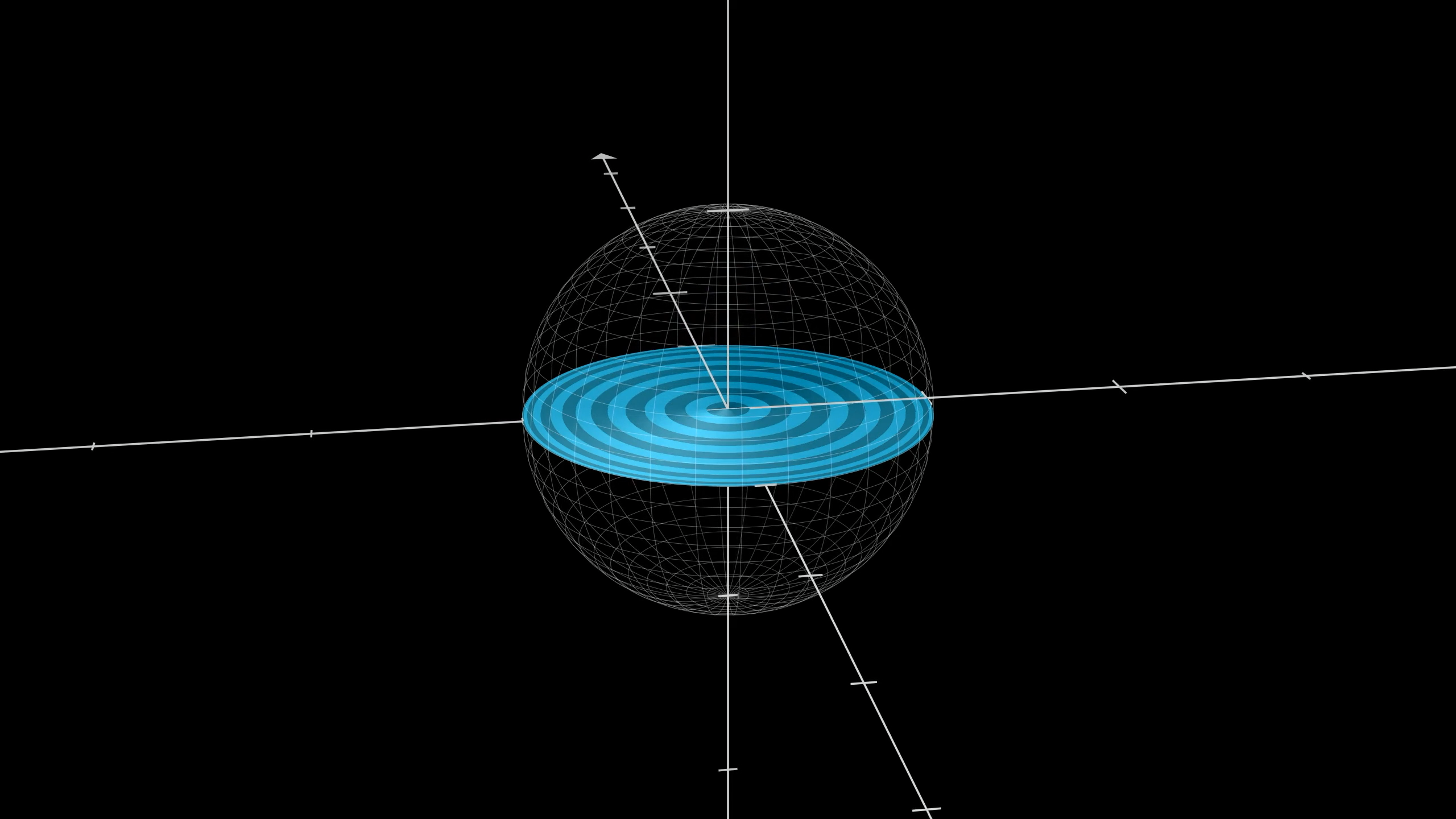

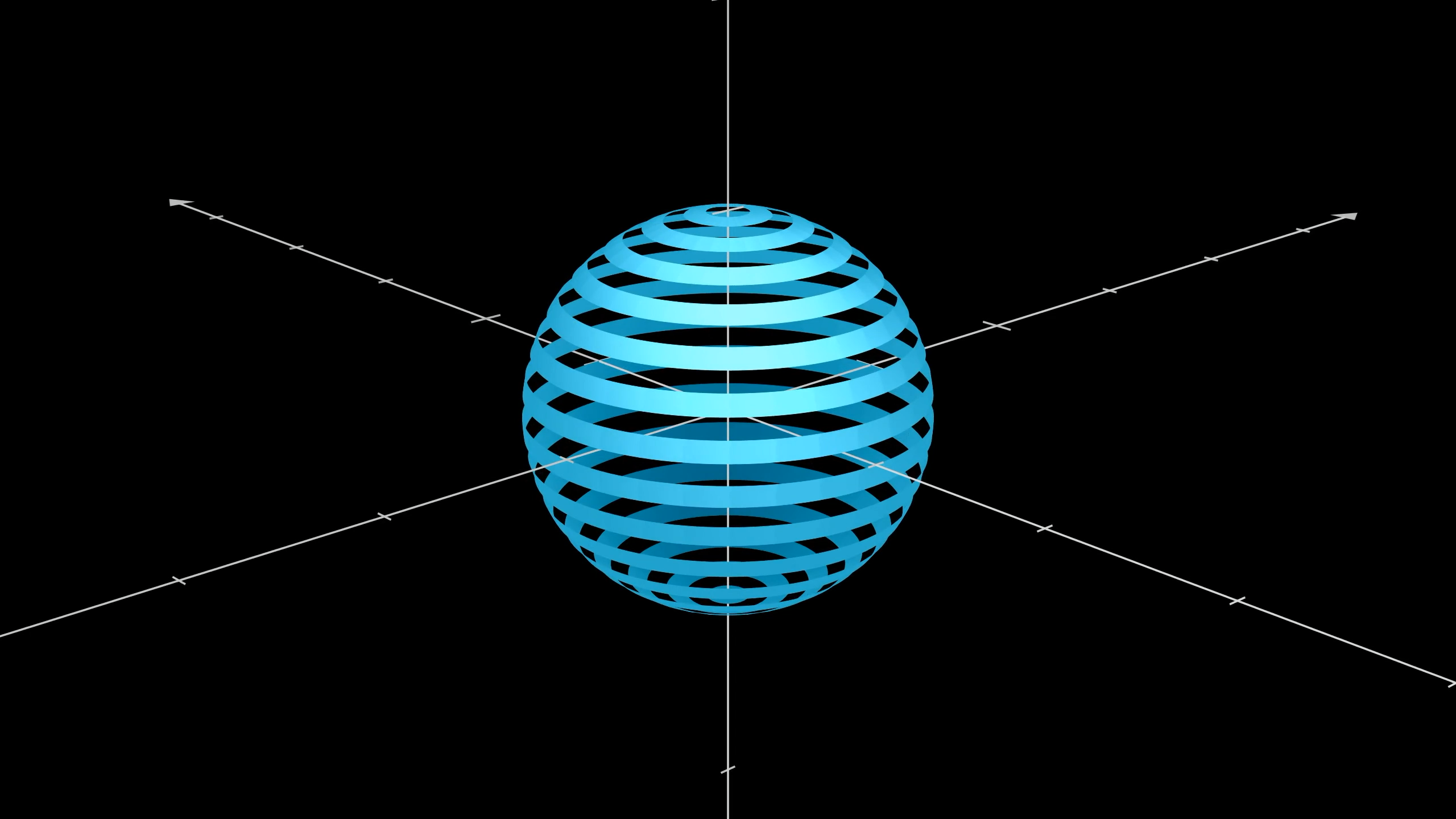

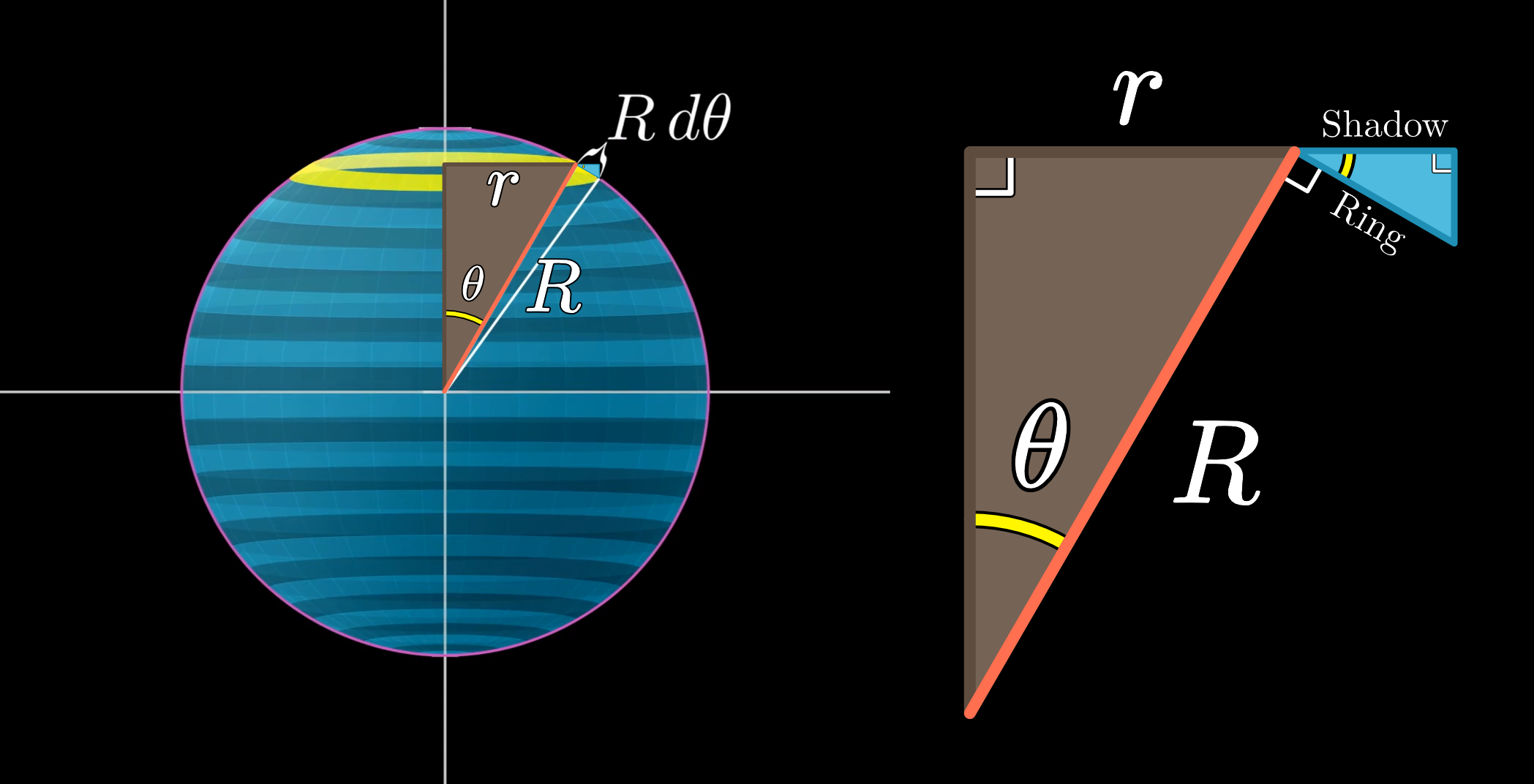

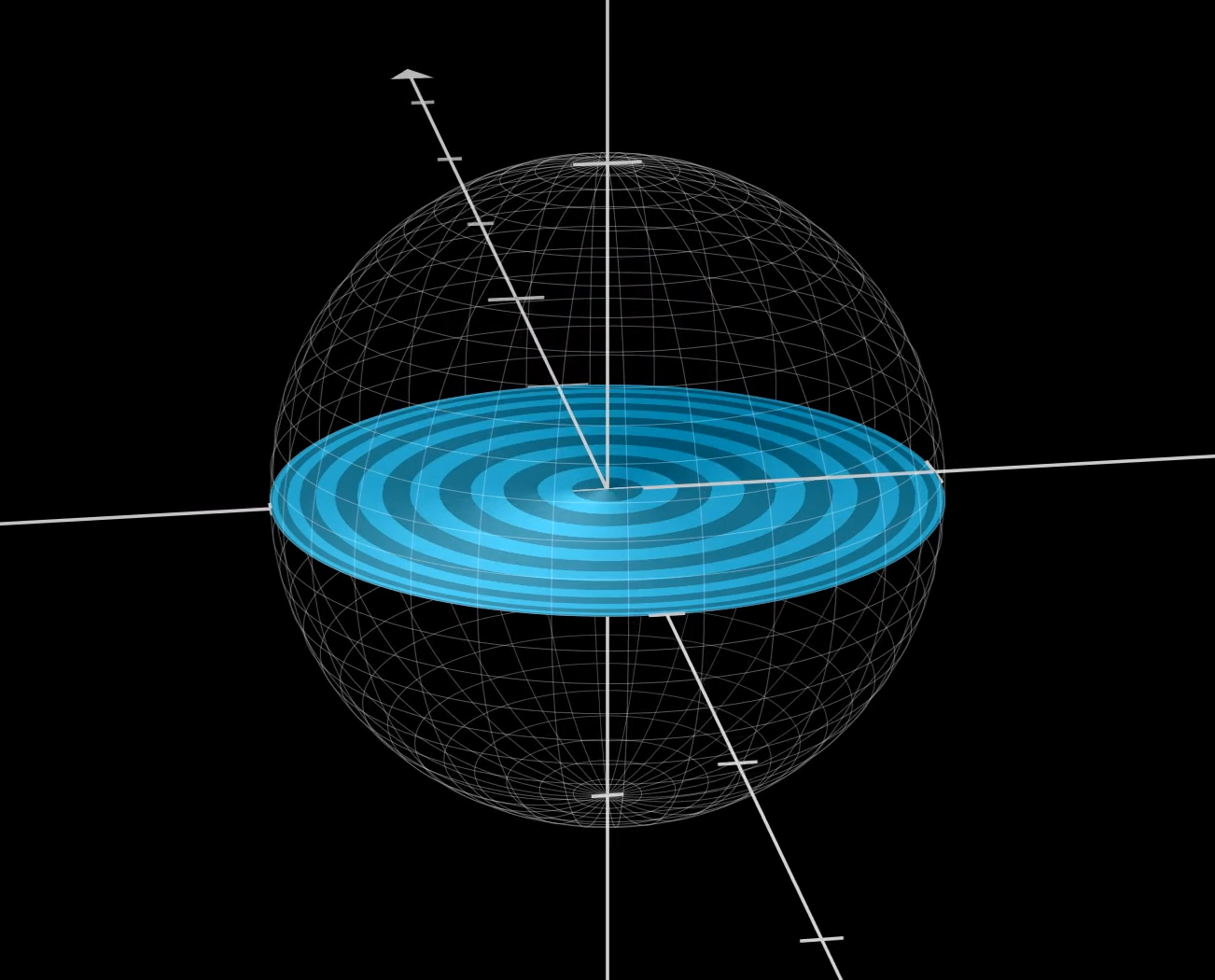

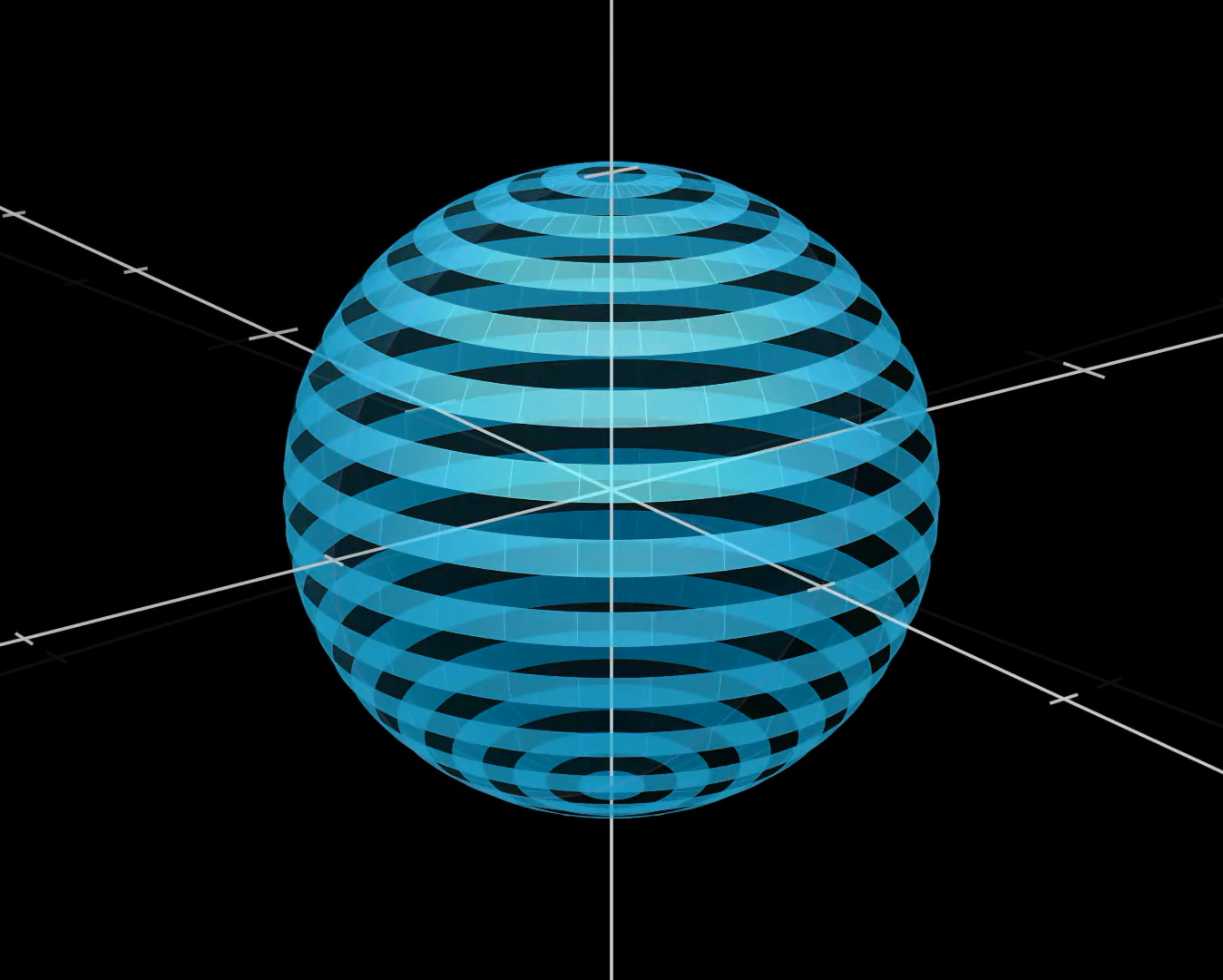

At a high level, the approach will be to cut the sphere into many thin rings parallel to the xy-plane.

We will compare the area of these rings to the area of their shadows on the xy-plane.

The shadows of all the rings in the top hemisphere form a perfect circle.

All the shadows of the rings from the top hemisphere make up a circle with the same radius as the sphere. The main idea will be to show a correspondence between these ring shadows, and every 2nd ring on the sphere.

Here we are looking at every other ring of the sphere. Your goal will be to find a correspondence between the alternating rings shown here and the shadows of the top hemisphere rings, shown above.

Challenge mode here is to stop reading now and try to predict how that might go.

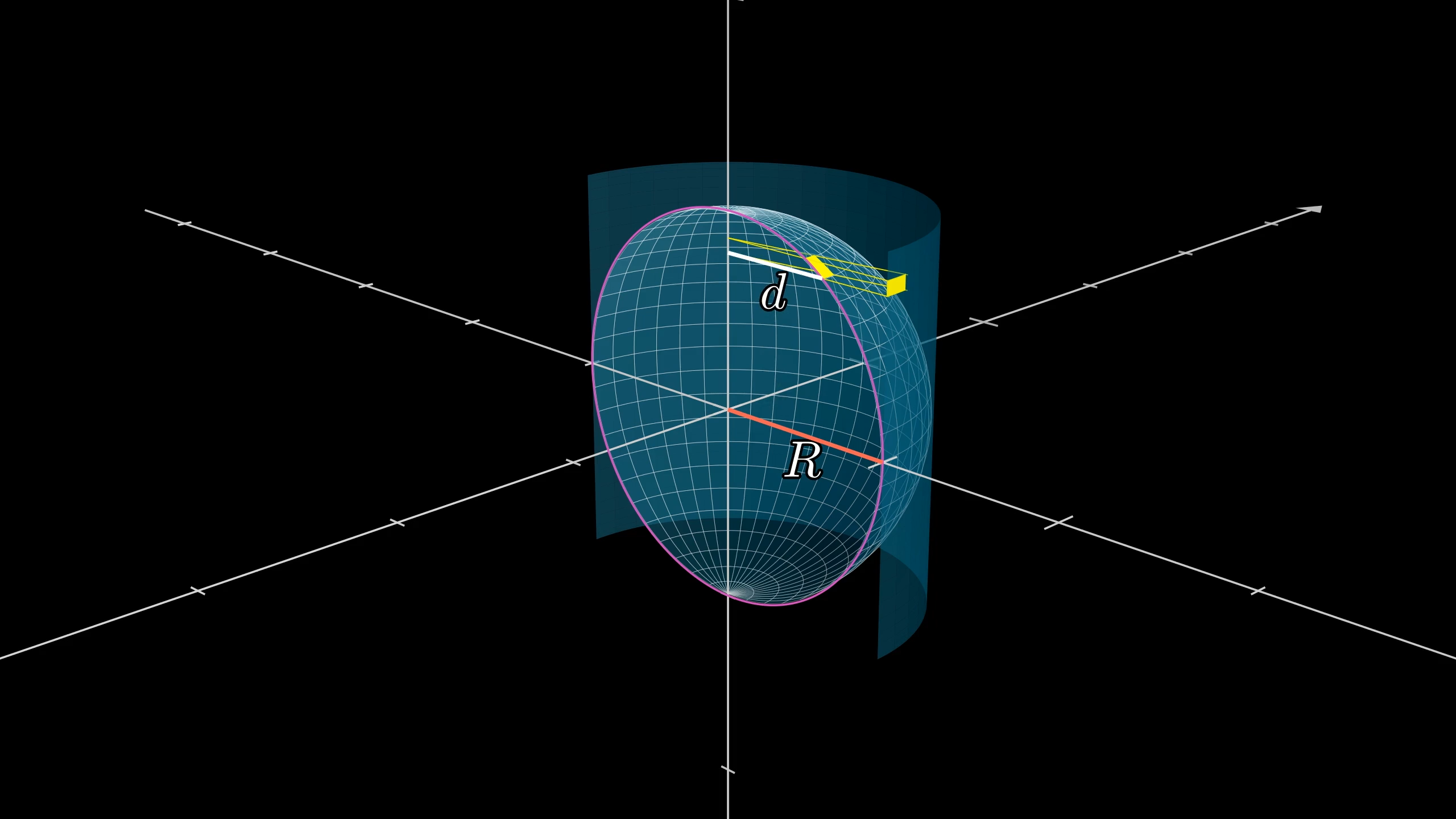

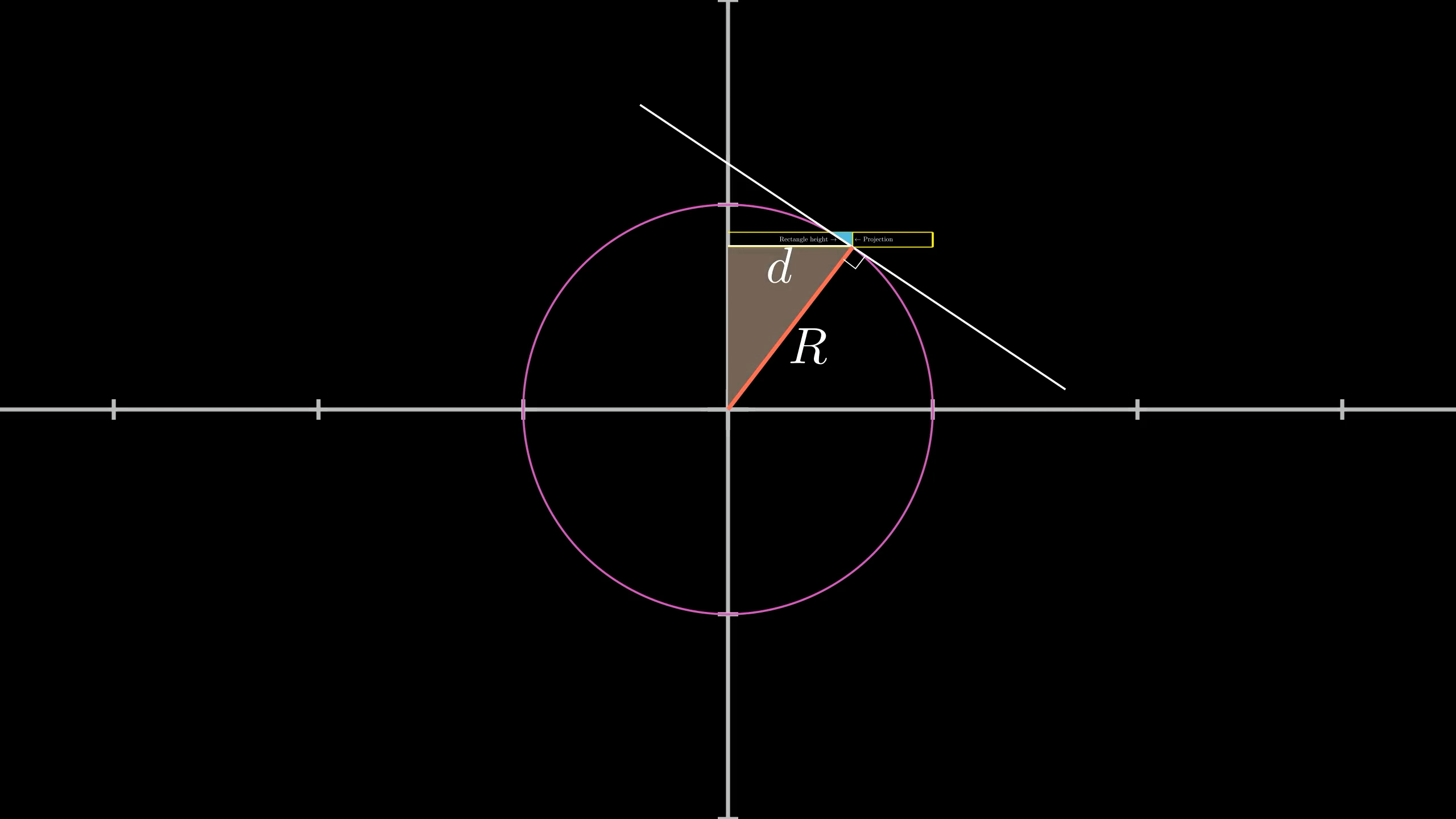

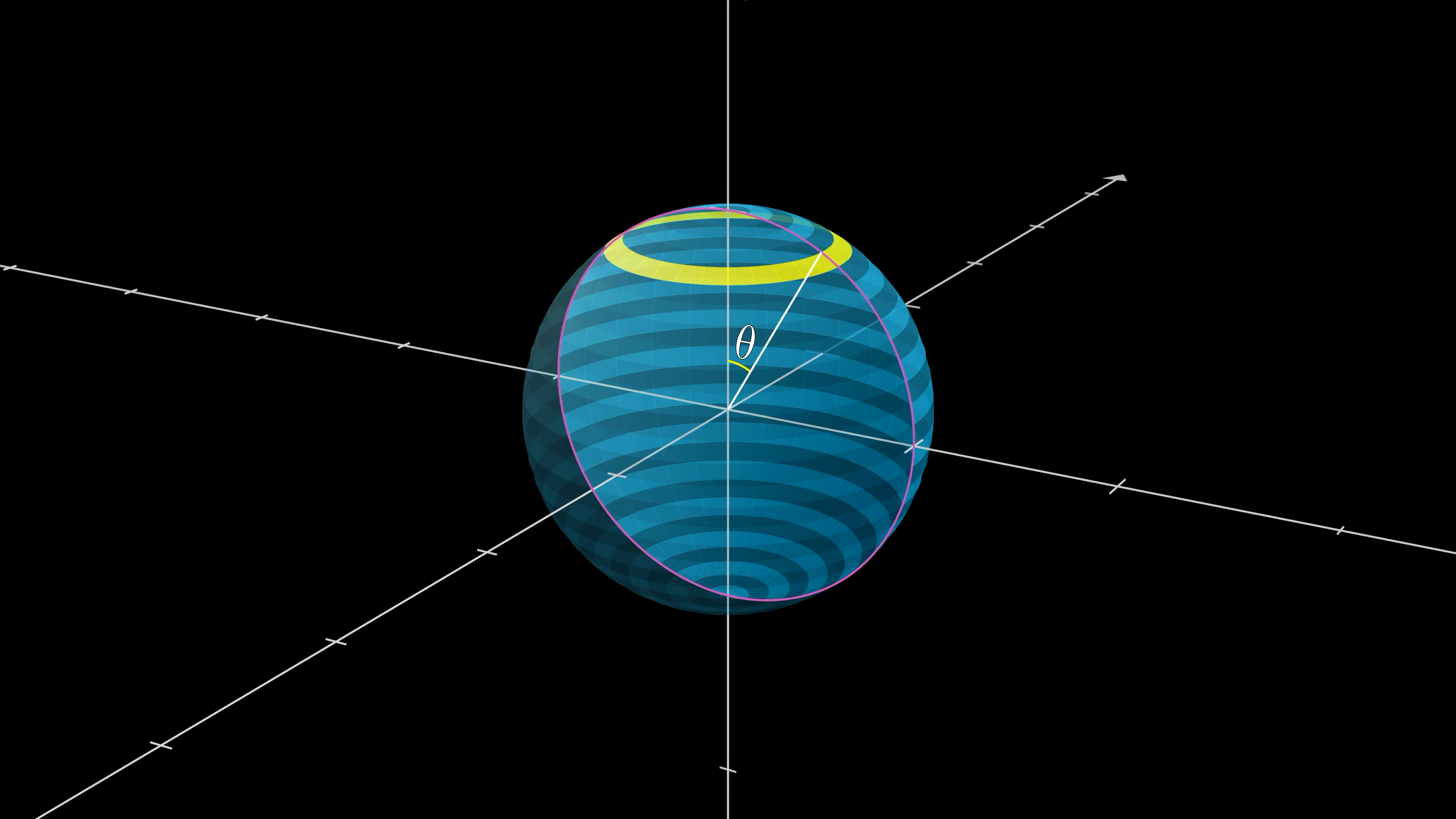

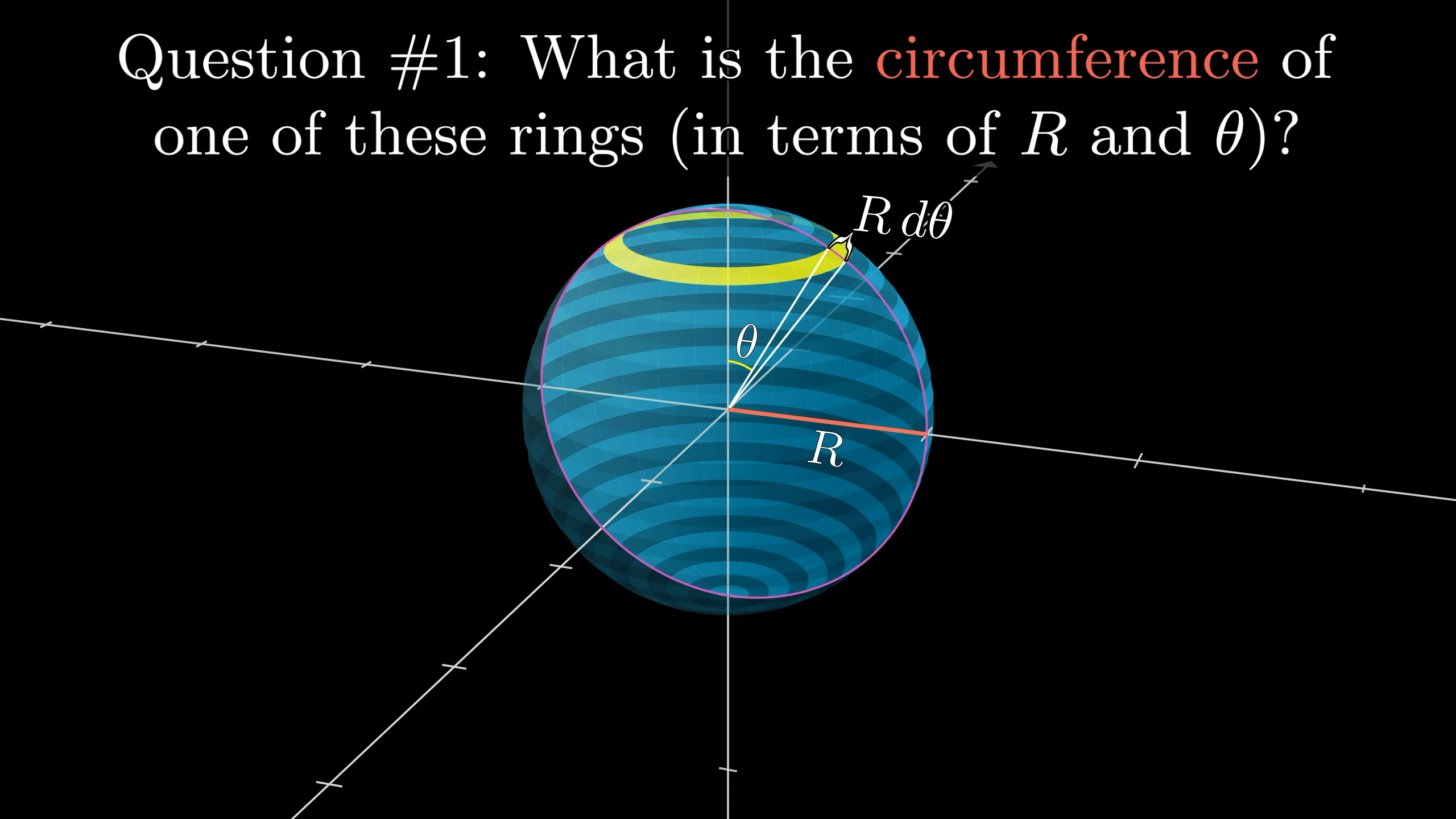

We’ll label each one of these rings based on the angle between the z-axis and a line out to the ring from the sphere’s center.

Each ring will be identified by its corresponding angle .

So ranges from 0 to 180 degrees, or to radians. And let’s call the change in angle from one ring to the next , which means the thickness of one of these rings will be , where is the radius of the sphere.

Alright, structured exercise time. We’ll ease in with a warm-up.

Question 1

What is the circumference of the inner edge of this ring, in terms of and ?

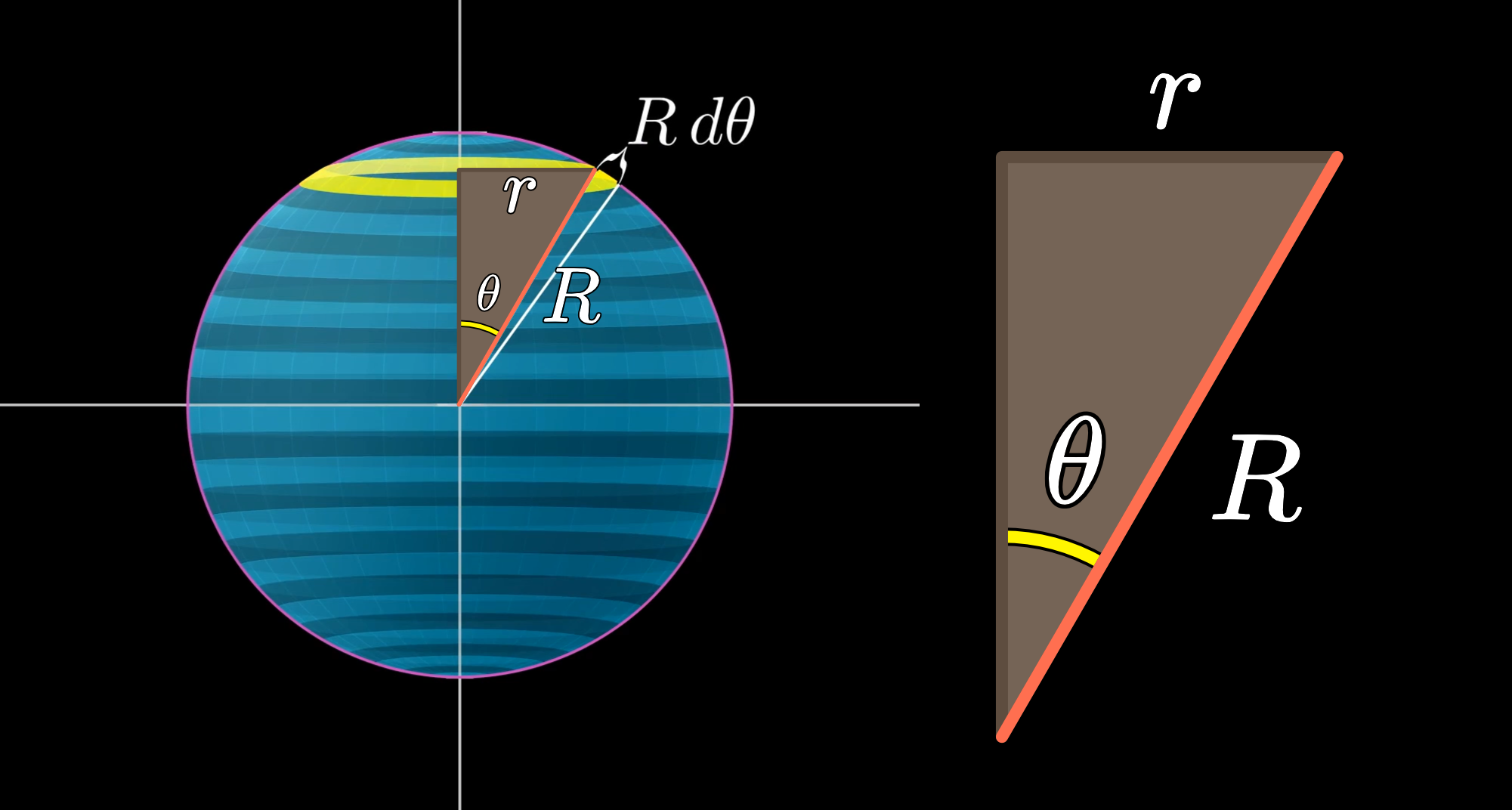

The circumference of the ring depends on its radius. The ring's radius is the distance from the z-axis to the ring itself, which I'll call lowercase . (Note that we're not talking about the radius of the sphere, which we're calling capital .)

can be found using some trigonometry based on this right triangle:

We know that , which means that .

And now that we have the radius of the ring, finding its circumference is just a matter of multiplying by .

The circumference, then, is .

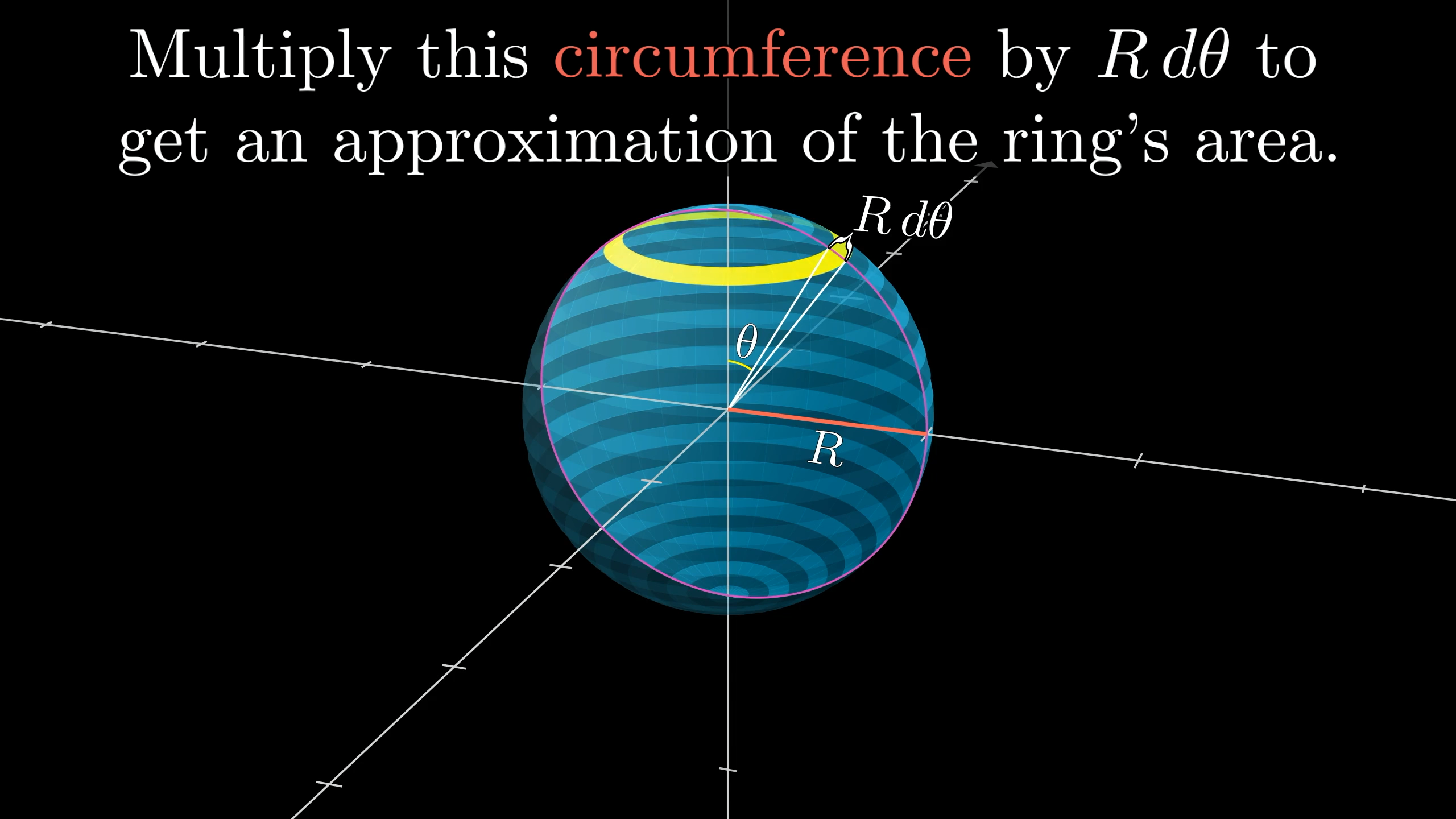

Now, go ahead and multiply your answer by the thickness to get an approximation for this ring’s area. (This approximation gets better and better as you chop up the sphere more and more finely.)

We found the circumference to be , so multiplying by gives an area of approximately for the ring at angle .

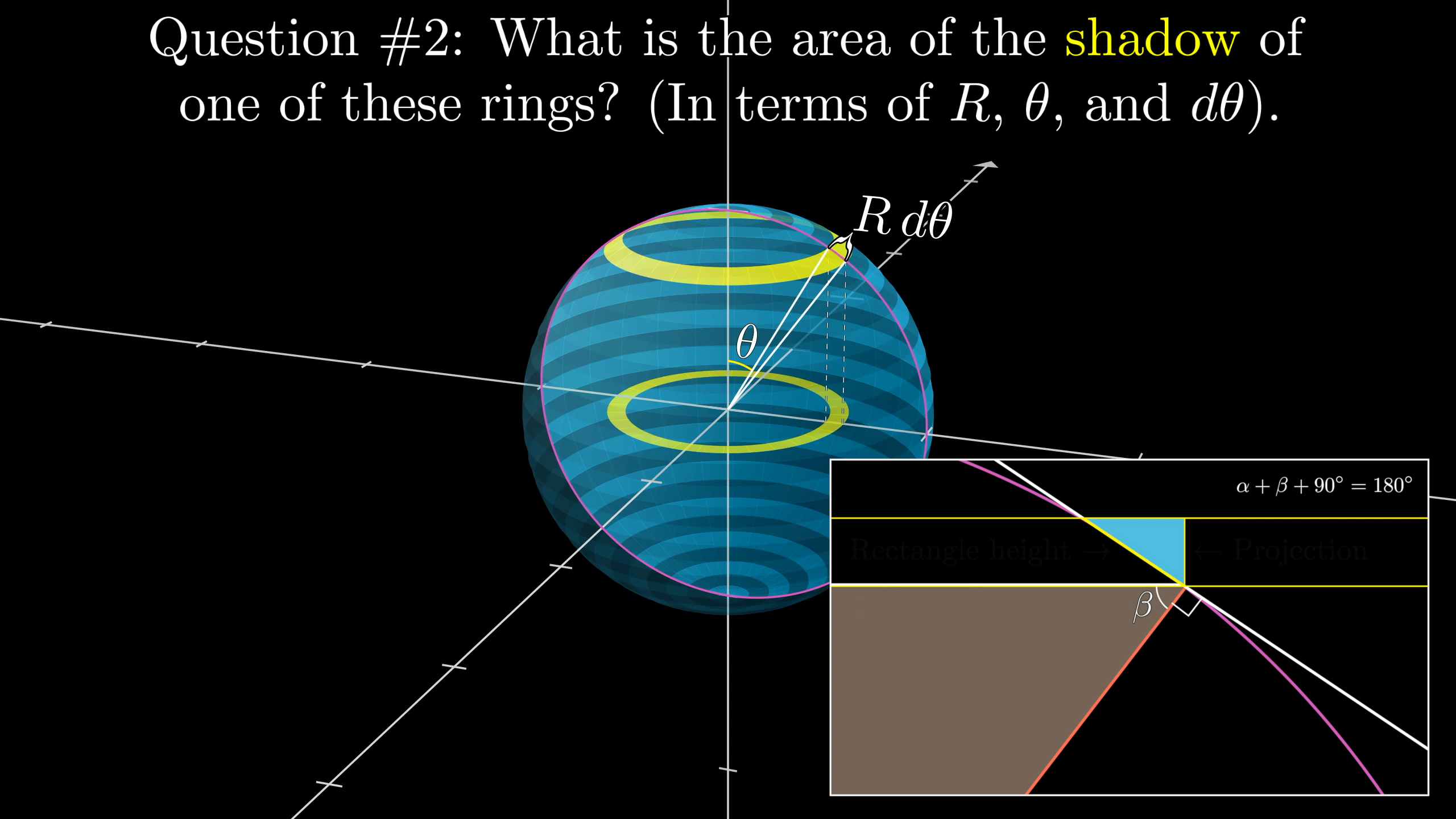

Question 2

What is the area of the shadow of one of these rings on the xy-plane? Express your answer in terms of , and .

(Hint: Think back to the similar right triangles used in the projection-onto-a-cylinder proof.)

Think back to the original projection-onto-a-cylinder proof. Remember how the height of the rectangle got squished as it was projected onto the cylinder, and the amount that it was squished depended on how tilted the rectangle was?

It's a very similar story here.

As the ring is projected down onto the xy-plane, its thickness will be squished down, and that squishing will depend on the angle . We will set up two similar right triangles, which should feel familiar:

The squishing factor we are trying to find is the ratio of the shadow thickness to the ring thickness. From the perspective of the angle in our little triangle, it's , or .

So the area of the shadow is just the area of the ring times , or .

Question 3

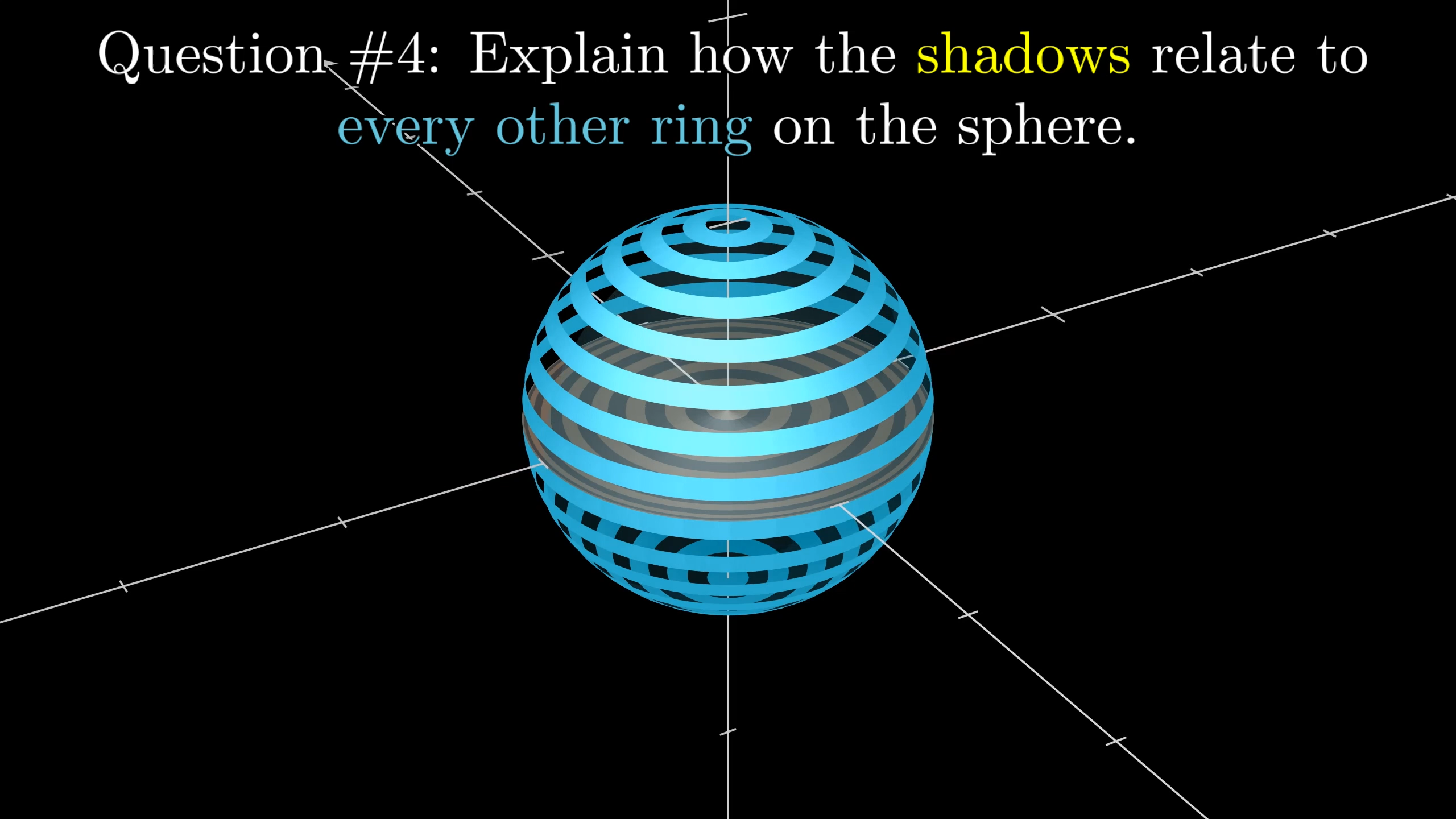

Each of these ring shadows has precisely half the area of one of these rings on the sphere. It’s not the one at angle theta straight above it, but another one. Which one?

We determined in question 2 that each ring at angle in the top hemisphere has a shadow of area .

So which ring on this sphere has an area of twice that, ?

The original overview of the problem gives a hint that helps eliminate some of the guesswork that might otherwise be involved in trying to find the matching ring:

"The main idea will be to show a correspondence between these ring shadows [in the top hemisphere], and every 2nd ring on the sphere."

So a reasonable correspondence might be to pair up each ring at with the ring at . That lets us cover alternating rings over the entire sphere, as hinted at above.

So, what is the area of the ring at ? Well, we can use our original ring area equation from question 1, but substitute in place of . That gives an area of .

We were hoping this would be double the area of the shadow of ring , , but it doesn't really appear to be.

This is where a trig identity can save the day:

Using this substitution, we find that the ring at has an area of , which is indeed double the area of the shadow of ring .

Therefore, the correspondence between ring 's shadow and ring has precisely the property we're looking for.

Question 4

I said from the outset that there is a correspondence between all the shadows from the northern hemisphere, which make up a circle with radius , and every other ring on the sphere. Use your answer to the last question to spell out exactly what that correspondence is.

Each shadow corresponds to one of the alternating rings of the sphere. The special property of this correspondence, spelled out in question 3, is that corresponding ring has an area double that of the shadow.

This means that the alternating rings have a total area that is exactly double the total area of the shadows.

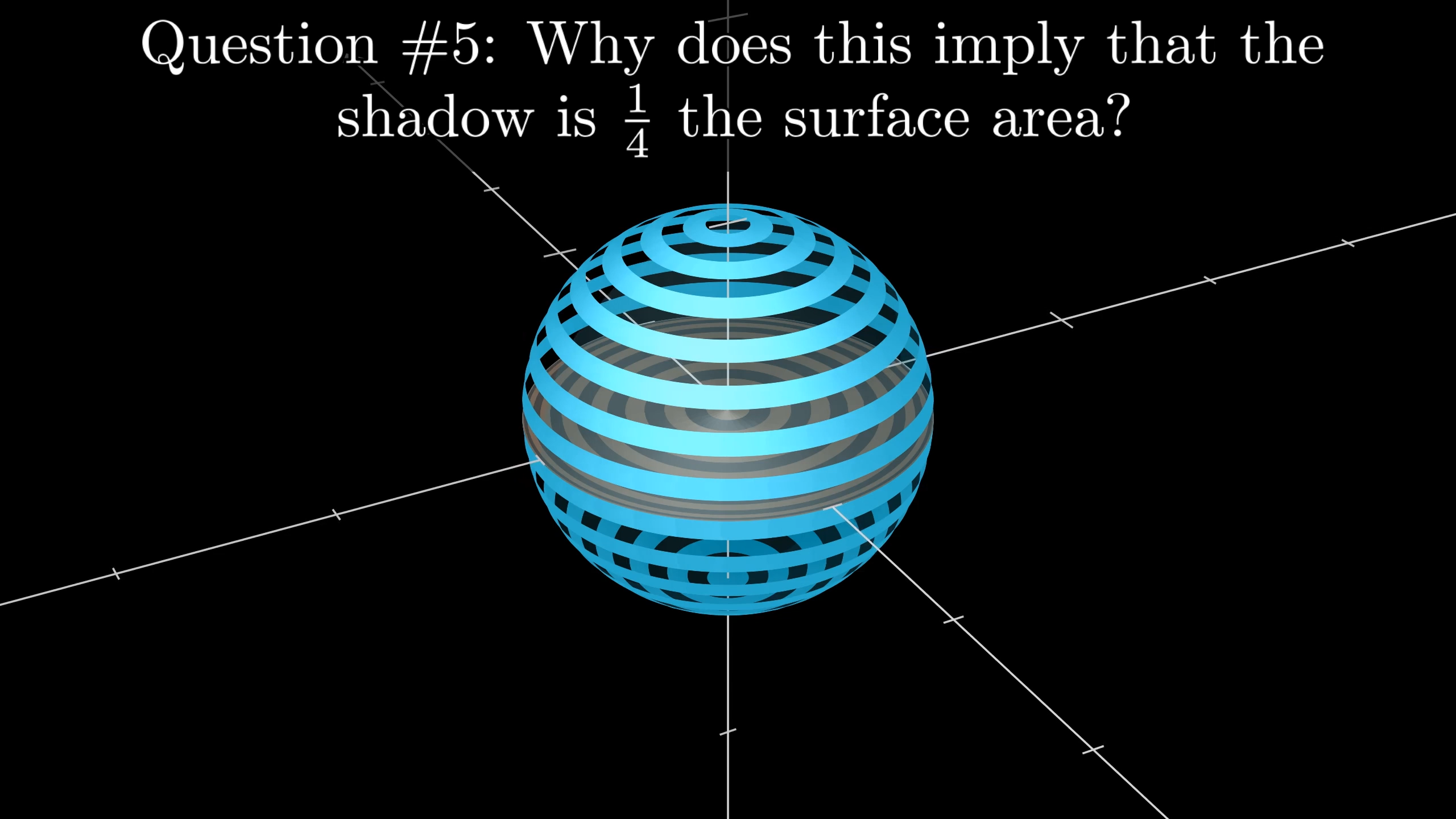

Question 5

Bring it on home. Why does this imply that the area of the circle is exactly ¼ the surface area of the sphere, particularly as we consider thinner and thinner rings?

All together, the top-hemisphere ring shadows form a perfect circle of radius on the xy-plane. This means that the sum of all their areas is exactly .

And because of our special correspondence, we know that the total area of all the alternating rings on the sphere is exactly double the total shadow area. So adding up the areas of these rings of the sphere gives a surface area of :

The total surface area of these rings is $2\pi R^2.

In the limit as these rings get ever thinner, the area of the alternating rings approaches half the total surface area. This is because each ring has approximately the same area as its immediate neighbors in that limiting case, so for example the sum of the areas of all the odd-numbered rings will equal the sum of the areas of the even-numbered rings. So to get the full surface area of the sphere, we double the total area of the alternating rings, which is .

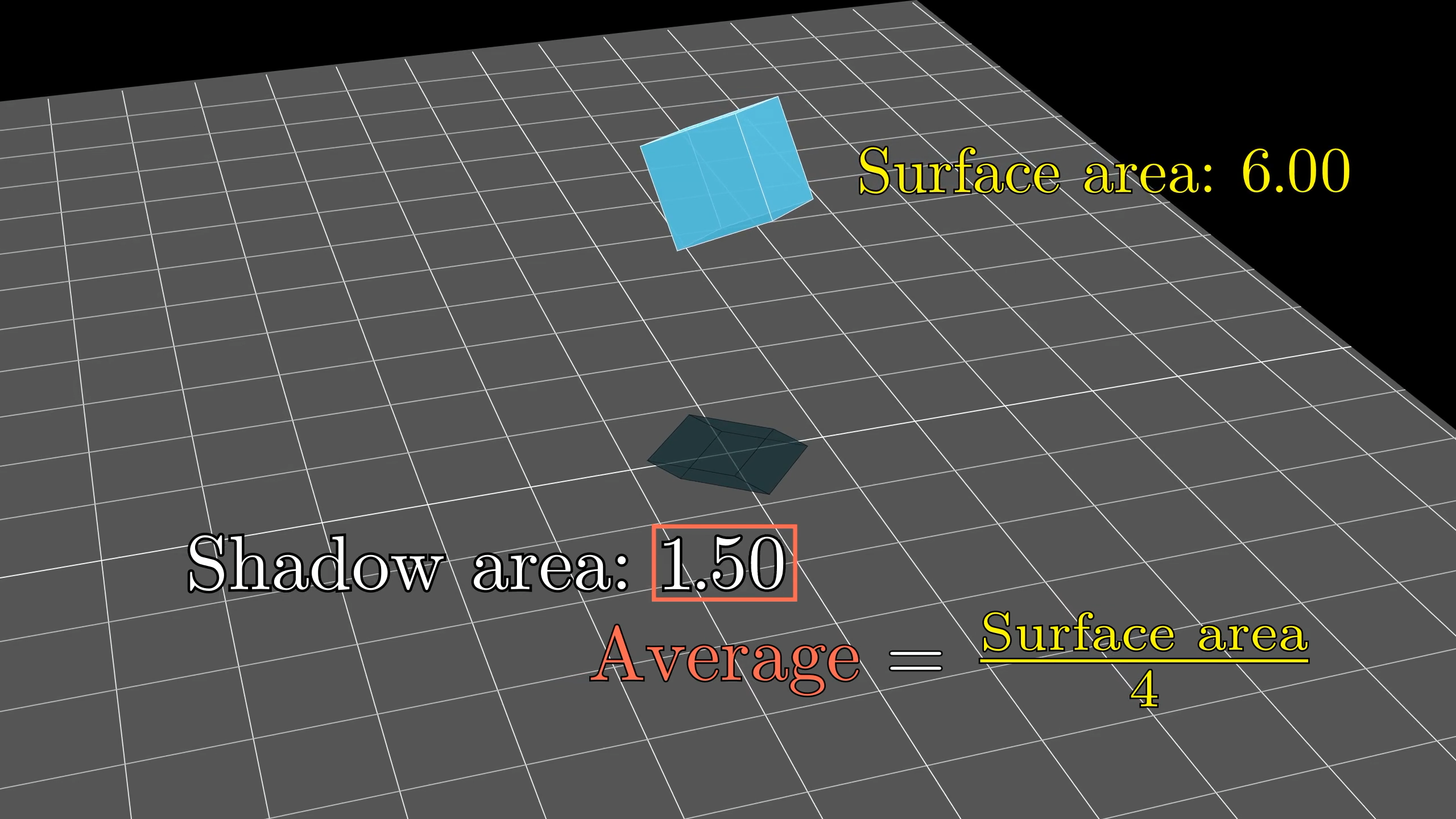

The more general shadow formula

And finally, I’d be remiss not to make a brief mention of the fact that the surface area of a sphere is a specific instance of a much more general fact: If you take any convex shape, and look at the average area of all its shadows, averaged over all possible orientations in 3D space, the surface area of the solid will be precisely 4 times that average shadow area.

As to why this is true? I’ll leave those details for another day.

Thanks

Special thanks to those below for supporting the original video behind this post, and to current patrons for funding ongoing projects. If you find these lessons valuable, consider joining.