Chapter 2The paradox of the derivative

"So far as the theories of mathematics are about reality, they are not certain; so far as they are certain, they are not about reality." - Albert Einstein

The goal here is simple: Explain what a derivative is. Thing is, though, there’s some subtlety to this topic, and some potential for paradoxes if you’re not careful, so the secondary goal is that you have some appreciation for what those paradoxes are and how to avoid them.

It’s common for people to say that the derivative measures “instantaneous rate of change”, but if you think about it, that phrase is actually an oxymoron. Change is something that happens between separate points in time, and when you blind yourself to all but a single instant, there is no more room for change.

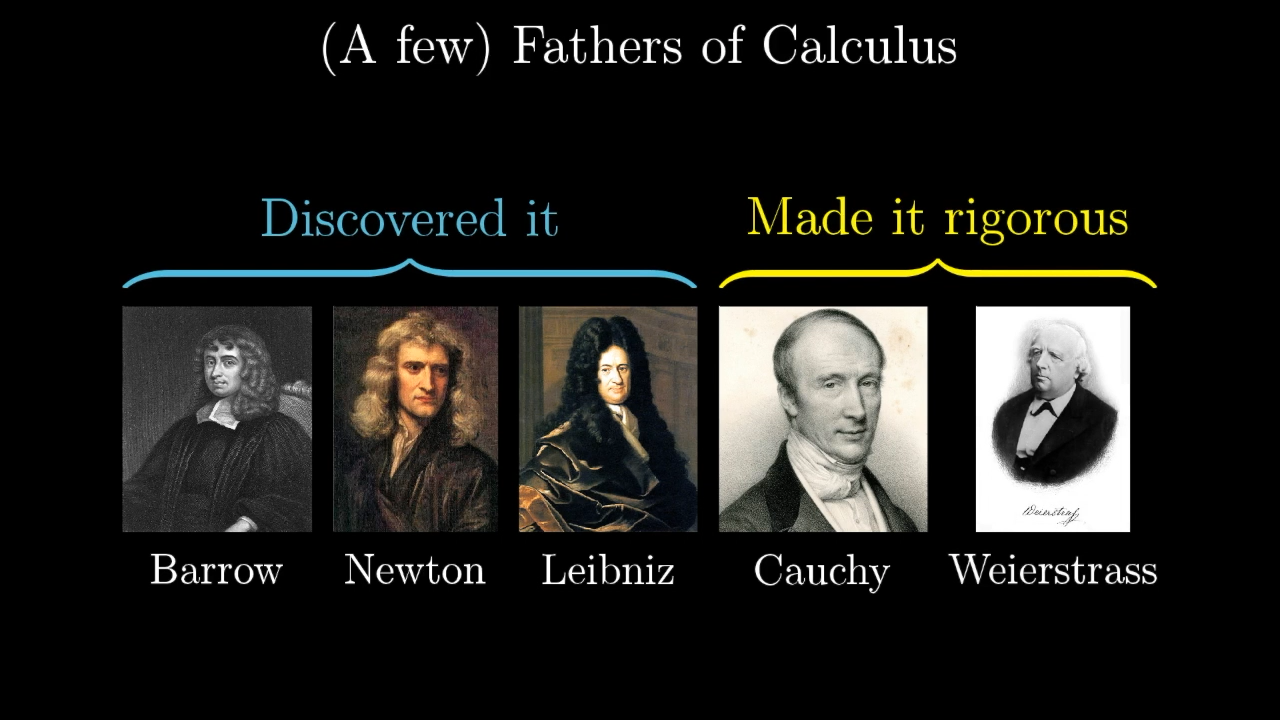

Even if the phrase “instantaneous rate of change” doesn’t, strictly speaking, make sense, there is a very real concept which this phrase is meant to invoke. It took quite a bit of cleverness from the inventors of calculus to nail down this idea, which we now call the derivative.

(A few) Inventors of Calculus

Car Moving

As our central example, imagine a car that starts at some point , speeds up, then slows to a stop at some point , meters away, all over the course of seconds.

Position of car between two points at different points in time.

We could graph this motion, letting a vertical axis represent the distance traveled, and a horizontal axis represent time.

Distance Traveled (meters)

At each time , represented with a point on the horizontal axis, the height of the graph tells us how far the car has traveled after that amount of time. It’s common to name a distance function like this . We’d use the letter for distance, except that it already has another full time job in calculus.

For example, the height of the graph tells us that after seconds the car has traveled a little more than meters.

Distance (meters) traveled at .

Initially this curve is quite shallow, since the car is slow at the start. During the first second, the distance traveled by the car hardly changes at all. For the next few seconds, as the car speeds up, the distance traveled in a given second gets larger, corresponding to a steeper slope in the graph. And as it slows towards the end, the curve shallows out again.

This figure highlights the slope of the graph for different intervals of time, where slope is calculated as the rise over run for each interval.

If we were to plot the car’s velocity in meters per second as a function of time, it might look like this green bump shown in the graph below.

Distance and Velocity Graphs

Shortly after time , the velocity is very small. Up to the middle of the journey, the car builds up to some maximum velocity, covering a relatively large distance in each second. Then it slows back down to a speed of meters per second.

Position and Velocity

These two curves are highly related to each other; if you change the specific distance vs. time function, you’ll have some different velocity vs. time function. We want to understand the specifics of this relationship. Exactly how does velocity depend on this distance vs. time function? For example, let’s look at a different distance vs. time function.

In this graph, the car starts from a stopped position, speeds up and slows down back to a stopped position at seconds time. Then the car speeds up and slows down again to a stopped position at seconds time.

It’s worth taking a moment to think critically about what velocity actually means here. Intuitively, we all know what velocity at a given moment means, it’s whatever the car’s speedometer shows at that moment. And intuitively, it might make sense that velocity should be higher at times when the distance function is steeper; when the car traverses more distance per unit time.

For example, given the graph of the car's position, shown below, at what time is the car going fastest? The car is going fastest at

But the funny thing is, velocity at a single moment makes no sense. Or at least if we think of velocity as a change in distance divided by a change in time, then isolating our view to a single moment leaves no room for both these changes. If I show you a picture of a car, a snapshot in an instant, and ask you how fast it’s going, you’d have no way of telling me.

What you need are two points in time to compare, perhaps comparing the distance traveled after seconds to the distance traveled after second. That way, you can take the change in distance over the change in time. For example, the two snapshots in time below show the position of the car.

Using this information, we can calculate the velocity of the car for this time interval.

That’s what velocity is, the distance traveled over a given amount of time.

So how is it that we’re looking at a function for velocity that only takes in a single value for , a single snapshot in time. It’s weird, isn’t it? We want to associate each individual point in time with a velocity, but computing velocity requires comparing two points in time.

If that feels strange and paradoxical, good! You’re grappling with the same conflict that the inventors of calculus did, and if you want a deep understanding of rates of change, not just for a moving car, but for all sorts of scenarios in science, you’ll need a resolution to this apparent paradox.

Rates of Change

First let’s talk about the real world, then we’ll go into a purely mathematical one. Think about how you might build an actual speedometer for a car.

At some point, say seconds into the journey, the speedometer might measure how far the car goes in a very small amount of time, perhaps the distance traveled between seconds and seconds. Then it would compute the speed in meters per second as that tiny distance, in meters, divided by that tiny time, seconds.

That is, a physical car can sidestep the paradox by not actually computing speed at a single point in time, and instead computing speed during very small amounts of time.

Let’s call that difference in time “”, which you might think of as seconds, and call the resulting difference in distance traveled “”. So the velocity at that point in time is over , the tiny change in distance over the tiny change in time.

Graphically, imagine zooming in on the point of the distance vs. time graph above . That is a small step to the right, since time is on the horizontal axis, and that is the resulting change in the height of the graph, since the vertical axis represents distance traveled.

So is the rise-over-run slope between two very close points on the graph.

Of course, there’s nothing special about the value , we could apply this to any other point in time, so we consider this expression to be a function of , something where I can give you some time , and you can give back to me the value of this ratio at that time; the velocity as a function of time.

Zoomed in image of rise over run at

So for example, when I had the computer draw this bump curve representing the velocity function, the one you can think of as the slope of this distance vs. time function at each point, here’s what I had computer do:

First, I chose some small value for , like . Then, I had the computer look at many times between and , and compute the distance function at , minus the value of this function at . That is, the difference in the distance traveled between the given time , and the time seconds after that. Then divide that difference by the change in time , and this gives the velocity in meters per second around each point in time.

With this formula, you can give the computer any curve representing the distance function , and it can figure out the curve representing the velocity .

The Paradox

So now would be a good time to pause, reflect, make sure this idea of relating distance to velocity by looking at tiny changes in time makes sense, because now we’re going to tackle the paradox of the derivative head-on. This idea of , a tiny change in the value of the function divided by a tiny change in the input , is almost what the derivative is.

Even though our car’s speedometer will look at an actual change in time like seconds to compute speed, and even though my program here for finding a velocity function given a position function also uses a concrete value of , in pure math, the derivative is not this ratio for any specific choice of . It is whatever value that ratio approaches as the choice for approaches .

Tangent Lines

Luckily, there is a really nice visual understanding for what it means to ask what this ratio approaches: For any specific choice of , this ratio is the slope of a line passing through two points on the graph, known as a secant line.

Well, as approaches , and those two points approach each other, the slope of that secant line approaches the slope of a line tangent to the graph at whatever point we’re looking at. So the true, honest to goodness derivative, is not the rise-over-run slope between two nearby points on the graph; it’s equal to the slope of a line tangent to the graph at a single point.

What does it mean if the slope of the tangent line is negative?

Notice what I’m not saying: I’m not saying that the derivative is whatever happens when is infinitely small, whatever that may mean, nor am I saying that you plug in for . Following what is a general theme in calculus, the idea is a two step process where you first consider a finitely small change, some actual number like , and then you ask what your answer approaches as this number approaches .

Even though change in an instant makes no sense, it does make sense to ask what the rate of change across smaller and smaller amounts of time approaches. It’s a sneaky backdoor way to talk reasonably about the rate of change at a single point in time. Isn’t that neat? It’s flirting with the paradox of change in an instant without ever needing to touch it.

What’s even more neat is how this potentially abstract notion of what many different rates of change approach ends up having such a clean and simple geometric meaning. Since the slope of the secant line between two nearby points approaches the slope of the tangent point at one of them as these points get closer together.

Since change in an instant still makes no sense, rather than interpreting the slope of this tangent line as an “instantaneous rate of change”, an alternate notion is to think of it as the best constant approximation for rate of change around a point.

Words on Notation

Throughout this article I’ve been using “” to refer to a tiny change in with some actual size, and “” to refer to the resulting tiny change in , which again has an actual size.

But the convention in calculus is that whenever you’re using the letter “” like this, you’re announcing that the intention is to eventually see what happens as approaches . For example, the honest-to-goodness derivative of the function is written as , even though the derivative is not a fraction, per se; it’s whatever that fraction approaches for smaller and smaller nudges in .

Example

A specific example should help here. You might think that asking about what this ratio approaches for smaller and smaller values of would make it much more difficult to compute, but counterintuitively it can make things easier. Let’s say a given distance vs. time function was exactly . So after second, the car has traveled meters, after seconds, it’s traveled meters, and so on. This function is shown below.

This figure graphs the position function and also highlights the point at .

What I’m about to do might seem somewhat complicated, but once the dust settles it really is simpler, and it’s the kind of thing you only ever have to do once in calculus. Let’s say you want the velocity, , at a specific time, like . And for now, think of having an actual size; we’ll let it go to in just a bit.

This figure illustrates the approximate velocity at .

The tiny change in distance between seconds and seconds is , and we divide by .

Since , we can apply the definition of the function, so the numerator becomes .

Now this, we can work out algebraically. And again bear with me, there’s a reason I’m showing you the details. Expanding the top gives the expression:

Now there are a lot of terms, but it simplifies. Those terms cancel out. Everything remaining has a in it, so we can divide that out. So the ratio has boiled down to plus two different terms that each have a in them.

So if we ask what happens as approaches , representing the idea of looking at smaller and smaller changes in time, we can ignore those! By eliminating the need to think of a specific , we’ve eliminated much of the complication in this expression! So what we’re left with is a nice clean . This means the slope of a line tangent to the point at on the graph of is exactly , or .

Of course, there was nothing special about choosing ; more generally we’d say the derivative of , as a function of , is .

That’s beautiful. This derivative is a quite complicated idea: We’ve got tiny changes in distance over tiny changes in time, but instead of looking at any specific tiny change in time we start talking about what this thing approaches. Yet we’ve ended up with such a simple expression: .

What is the velocity of the car at time

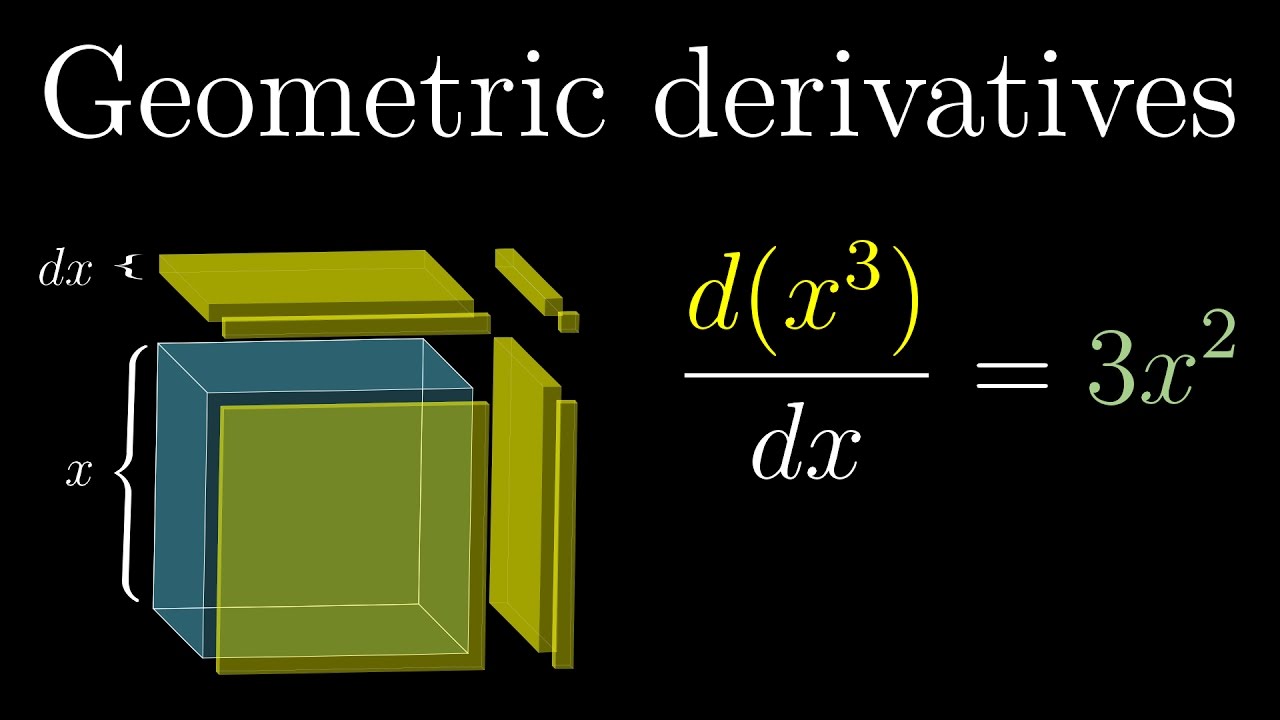

In practice, you would not go through all that algebra each time. Knowing that the derivative is is one of those things all calculus students learn to do immediately without rederiving each time, as quickly and automatically as you know a simple algebra rule, like . In the next chapter, we’ll see methods for thinking about this and many other derivative formulas in nice geometric ways.

The point I want to make by showing you all of the algebraic guts here is that when you consider the change in distance over a change in time for any specific value of , something like , you’d have kind of a mess.

But by considering what this ratio approaches as approaches , it lets you ignore much of that mess, and actually simplifies the problem.

That right there is the heart of why calculus becomes useful.

The Paradox at Time Zero

This example also sets the stage to think more concretely about why the notion of an instantaneous rate of change is paradoxical. Think about this car traveling according to this distance function, and consider its motion at moment . Now ask yourself: Is the car moving at that time?

On the one hand, we can compute its speed at that point using the derivative of this function, , which is at time .

Visually, this means the tangent line to the graph at that point is perfectly flat, so the car’s “instantaneous velocity” is , which suggests it’s not moving. But on the other hand, if it doesn’t start moving at time , when does it start moving? Really, pause and ponder this for a moment, is that car moving at ?

Take a moment to unpack what it actually means for the derivative of the distance function to be at this point. It means the best constant approximation for the car’s velocity around that point is meters per second. For example, between and seconds, the car does move, it moves meters. That’s very small, and importantly it’s very small compared to the change in time, an average speed of only meters per second.

For smaller and smaller nudges in time, this ratio of the change in distance over change in time approaches , though in this case it never actually hits it. So would you say this qualifies as moving at the time ? I would argue the question makes no sense, movement is something which happens between two points in time, so has no meaning in a given instant.

It’s tempting to say the derivative gives this notion meaning, and many people would happily say the car is not moving at , but it is moving for all times . For my part, I’d recommend not taking the phrase “instantaneous rate of change” too seriously, instead thinking of it as a conceptual shorthand for “the best constant approximation for the rate of change”.

Next Chapter

In the following chapters we’ll dig into how to compute the derivative of various functions. Along the way we’ll see how this fundamental idea of looking at tiny nudges to the output of a function caused by tiny nudges to its input lends itself to many beautiful geometric intuitions.

Thanks

Special thanks to those below for supporting the original video behind this post, and to current patrons for funding ongoing projects. If you find these lessons valuable, consider joining.