Why do prime numbers make these spirals?

Why Do Prime Numbers Make These Spirals?

I've had people ask me before why it is that mathematicians care so much about prime numbers. The role they play in math is similar to the role atoms play in chemistry. They're the fundamental building blocks of the integers, at least when multiplication is involved, and quite often solving some problem can be reduced to first solving it for primes. But honestly, a big part of why mathematicians care so much about primes is that they're hard to understand. Math is riddled with unsolved problems about primes, so for personality types who are drawn to difficult puzzles, prime numbers have a certain allure that's almost independent of the practical importance they have in math and related fields, like cryptography.

Part of the beauty of mathematics is how two seemingly unrelated concepts can be interconnected through an arbitrary choice. I first saw this pattern in a question on the Math Stack Exchange. It was asked by a user under the name dwymark, and answered by Greg Martin, and it relates to the distribution of prime numbers, as well as rational approximations for .

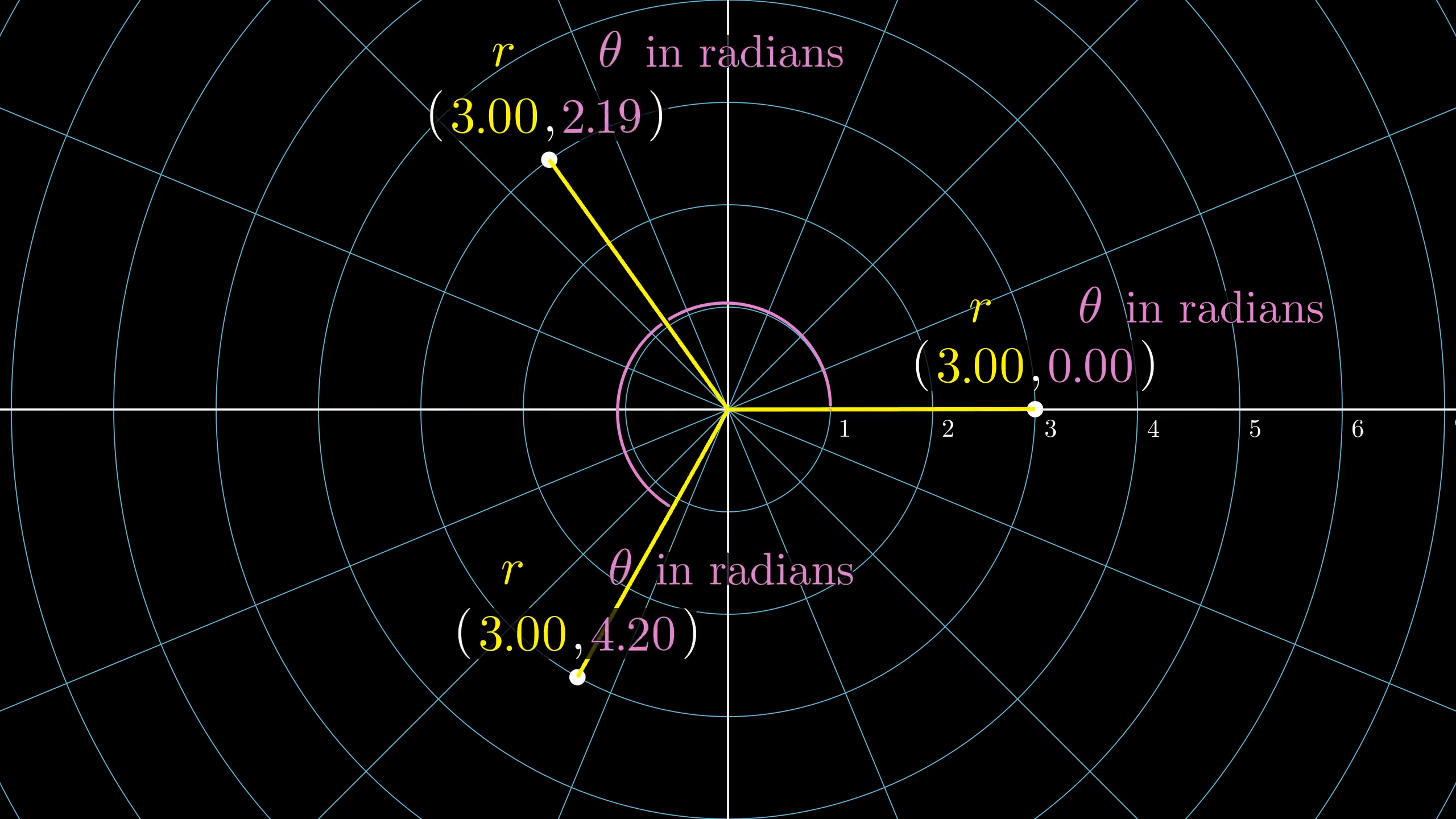

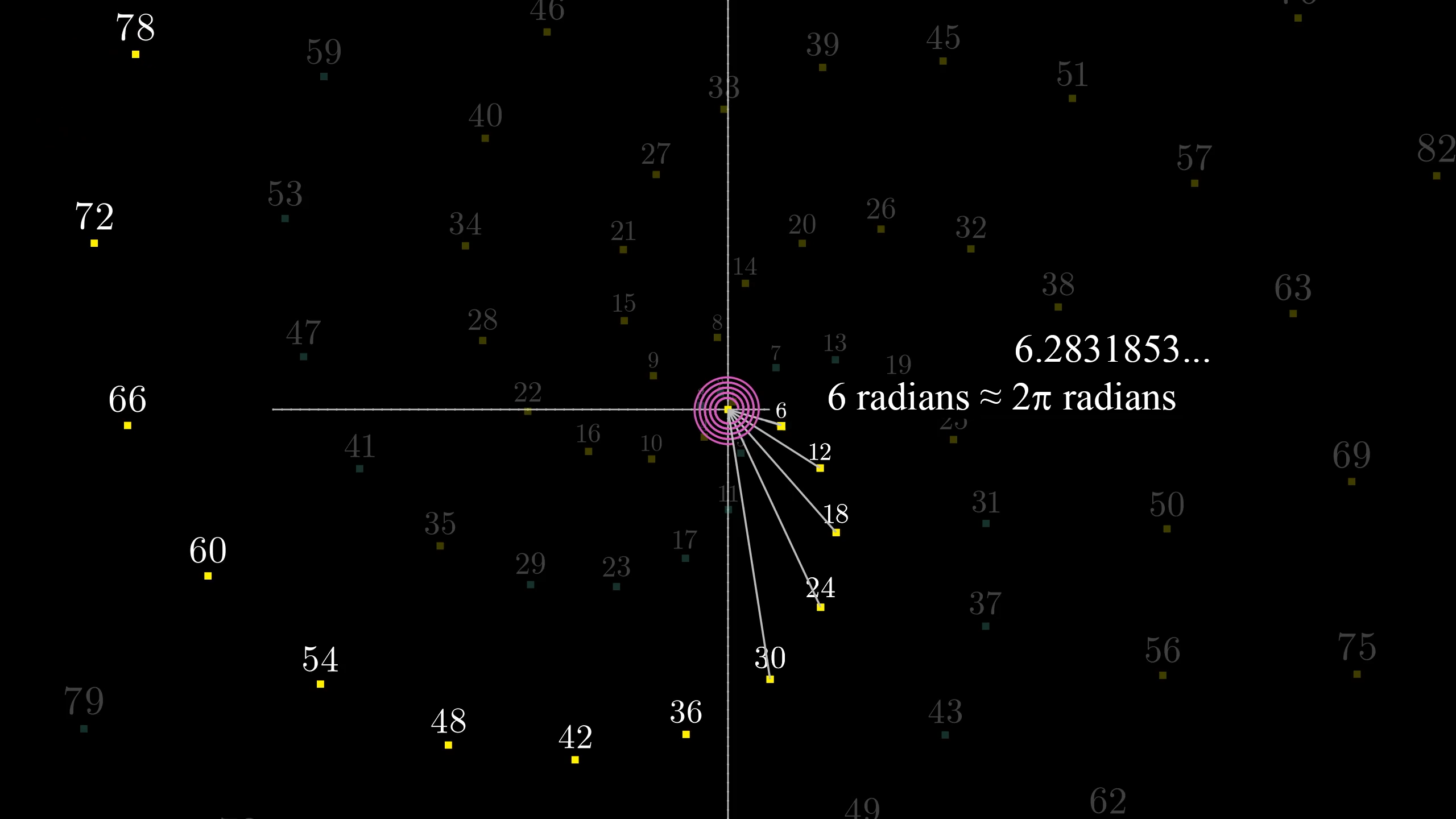

This user had been playing around with plotting data in polar coordinates. As a quick reminder, this means labeling points in 2D space, not with the usual -coordinates, but instead with a distance from the origin, commonly called for radius, together with the angle that line makes with the horizontal, commonly called theta, .

The angle is typically given in radians; that means an angle of is halfway around, and gives a full circle. Notice, polar coordinates are not unique, in the sense that adding to the angle doesn't change the location.

Which other point in polar coordinates does this point not equal?

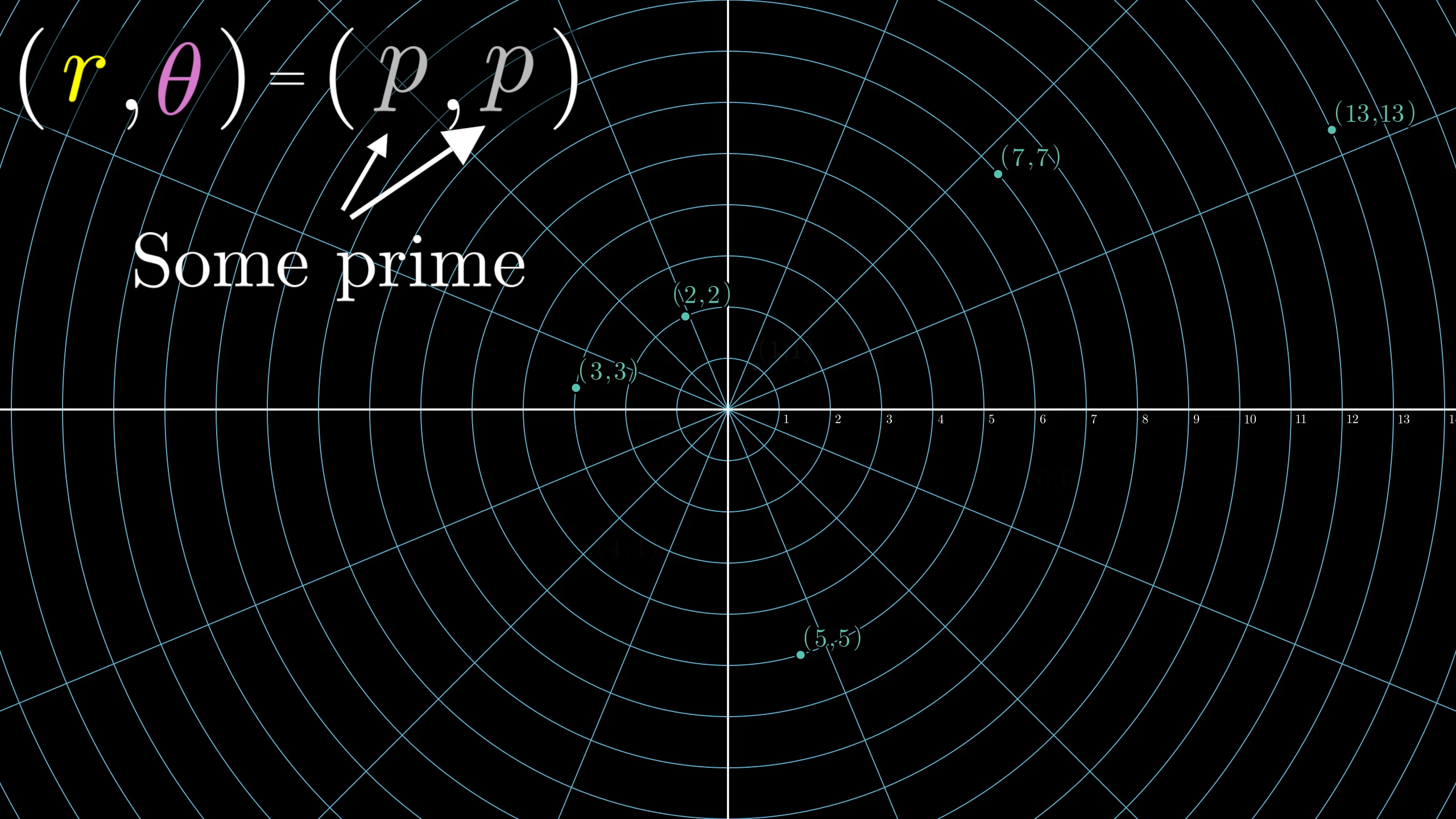

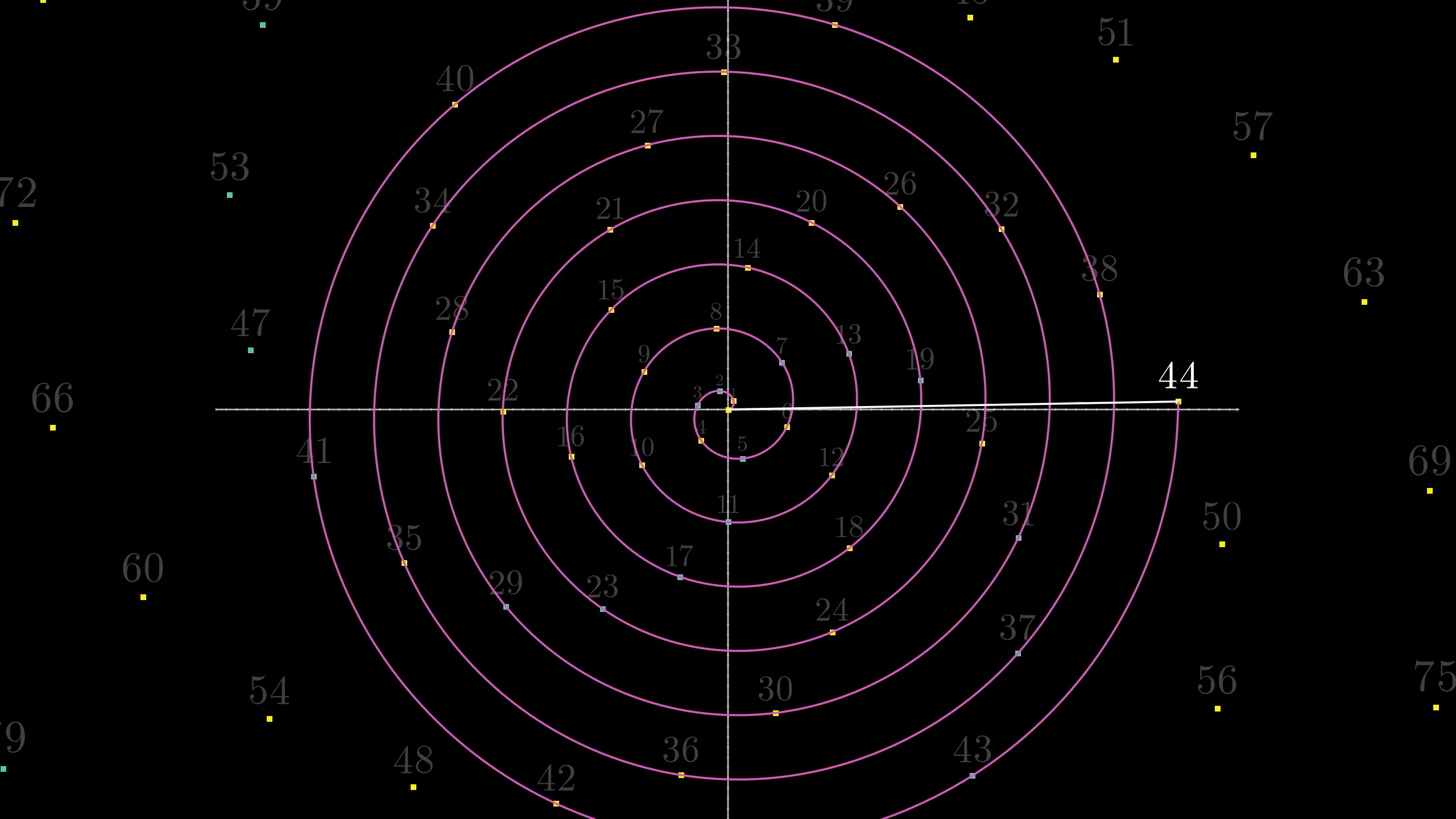

The pattern we'll look at centers around plotting points where both these coordinates are a given prime number.

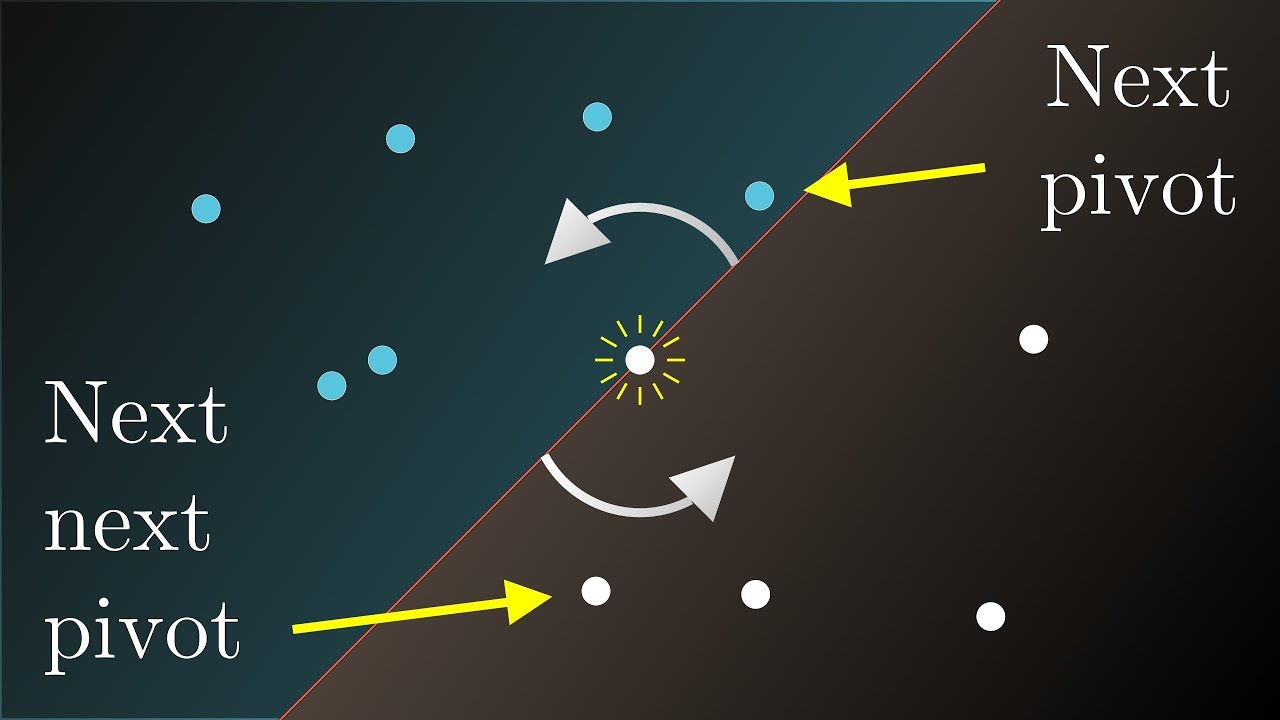

There's no practical reason to do this. It's just fun! We're frolicking in the playground of data visualization. Let's get a feel for this with all whole numbers, rather than just primes. The point sits a distance 1 away from the origin, with an angle of 1 radian. has twice the angle, and twice the distance. Similarly, to get to , you rotate one more radian, with a total angle now slightly less than , and you step one unit farther from the origin.

Make sure it's clear what's being plotted, because everything that follows depends on understanding it. Each step forward is like the tip of a clock hand which rotates 1 radian, a little less than of a turn, and grows longer by 1 unit. As you continue, these points spiral outward, forming what's known in the business as an "Archimedean spiral".

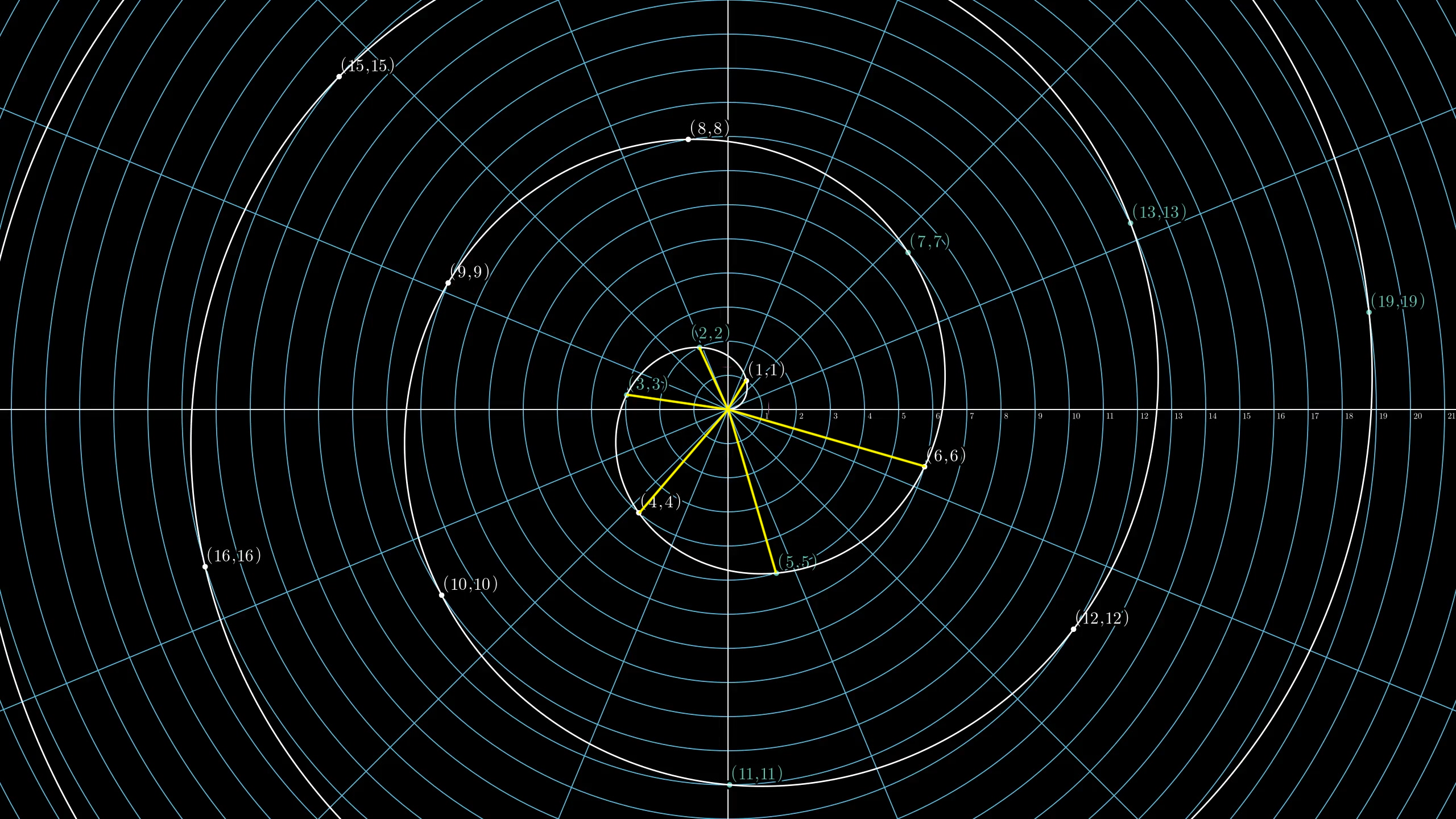

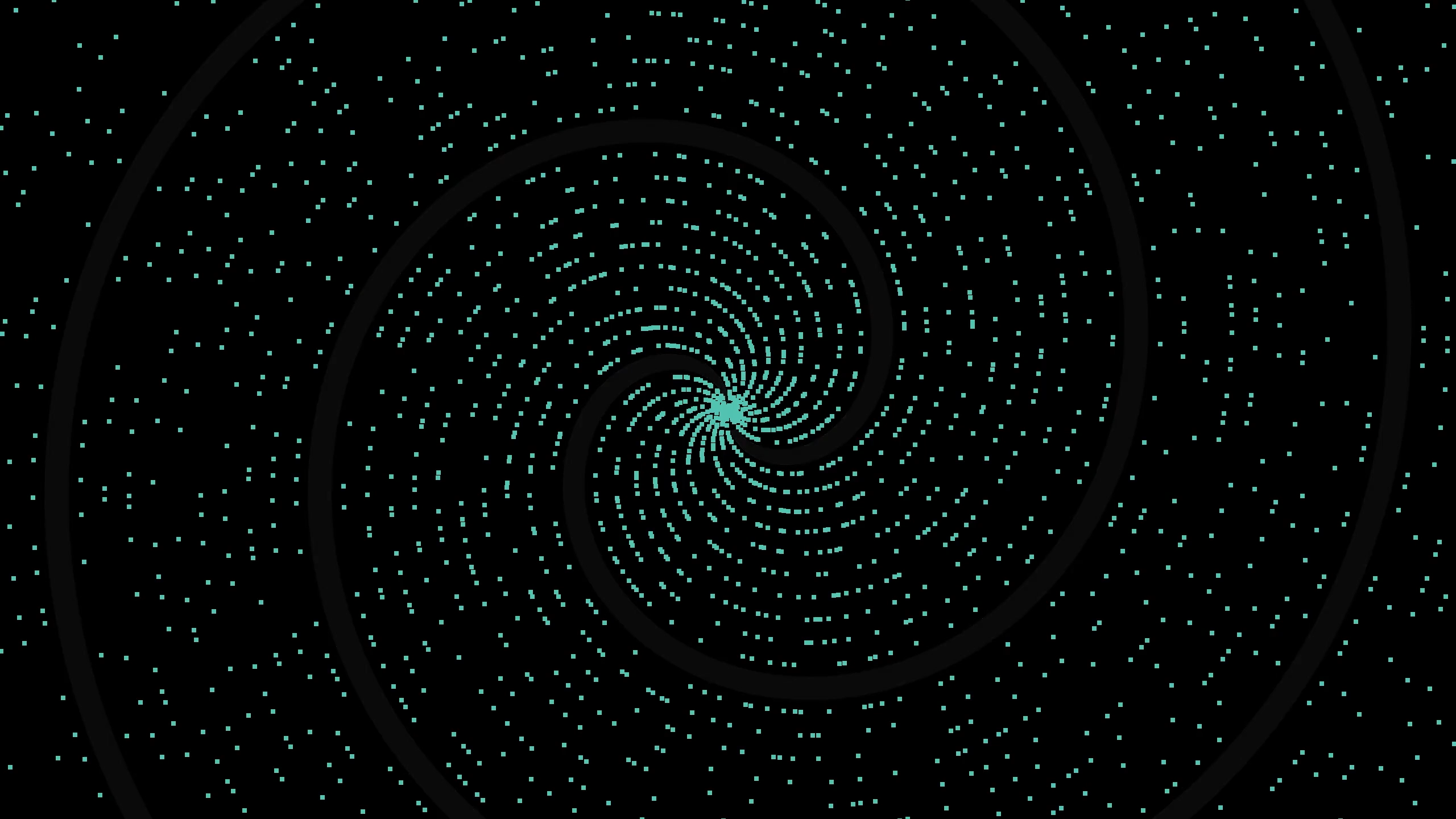

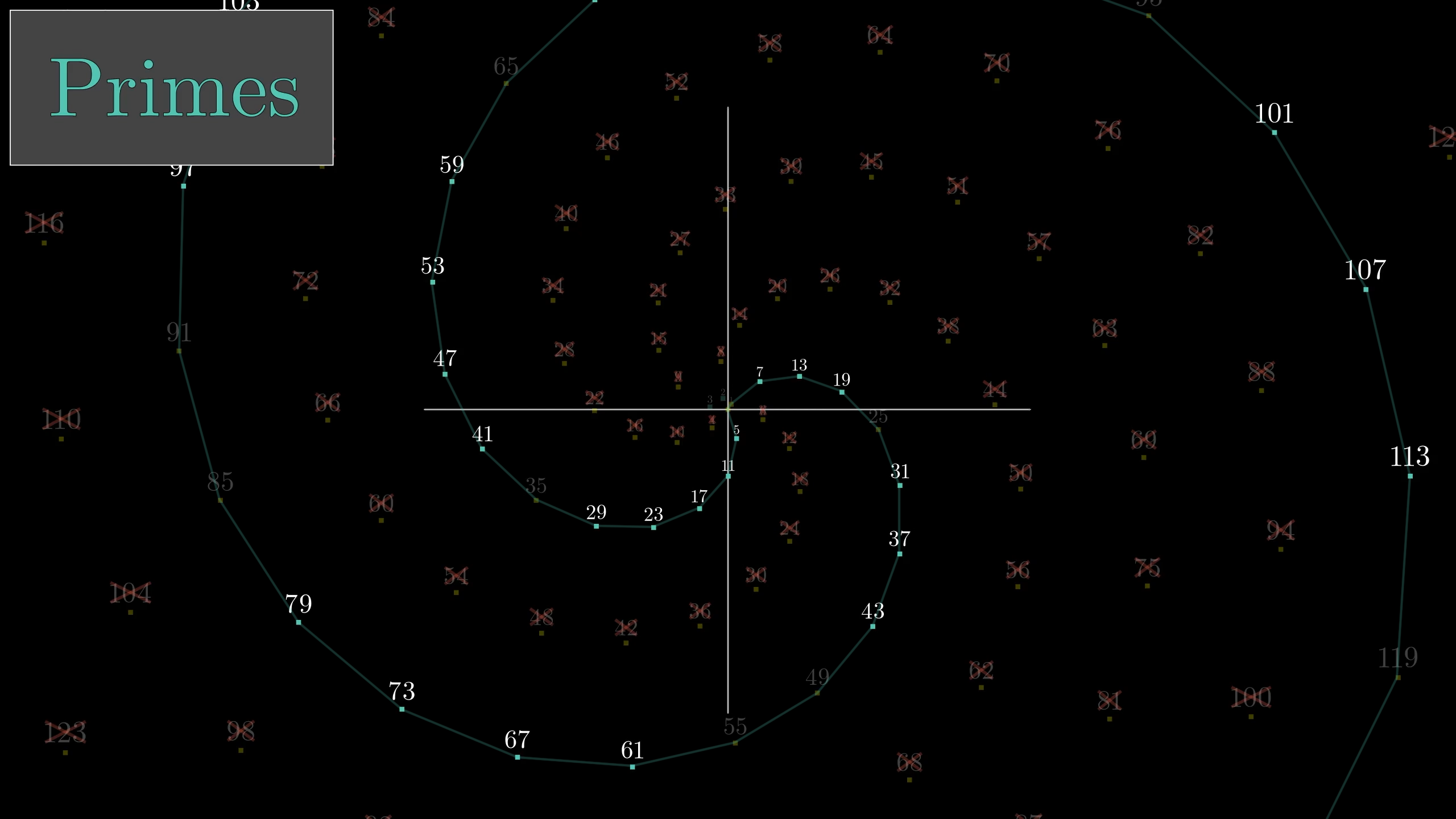

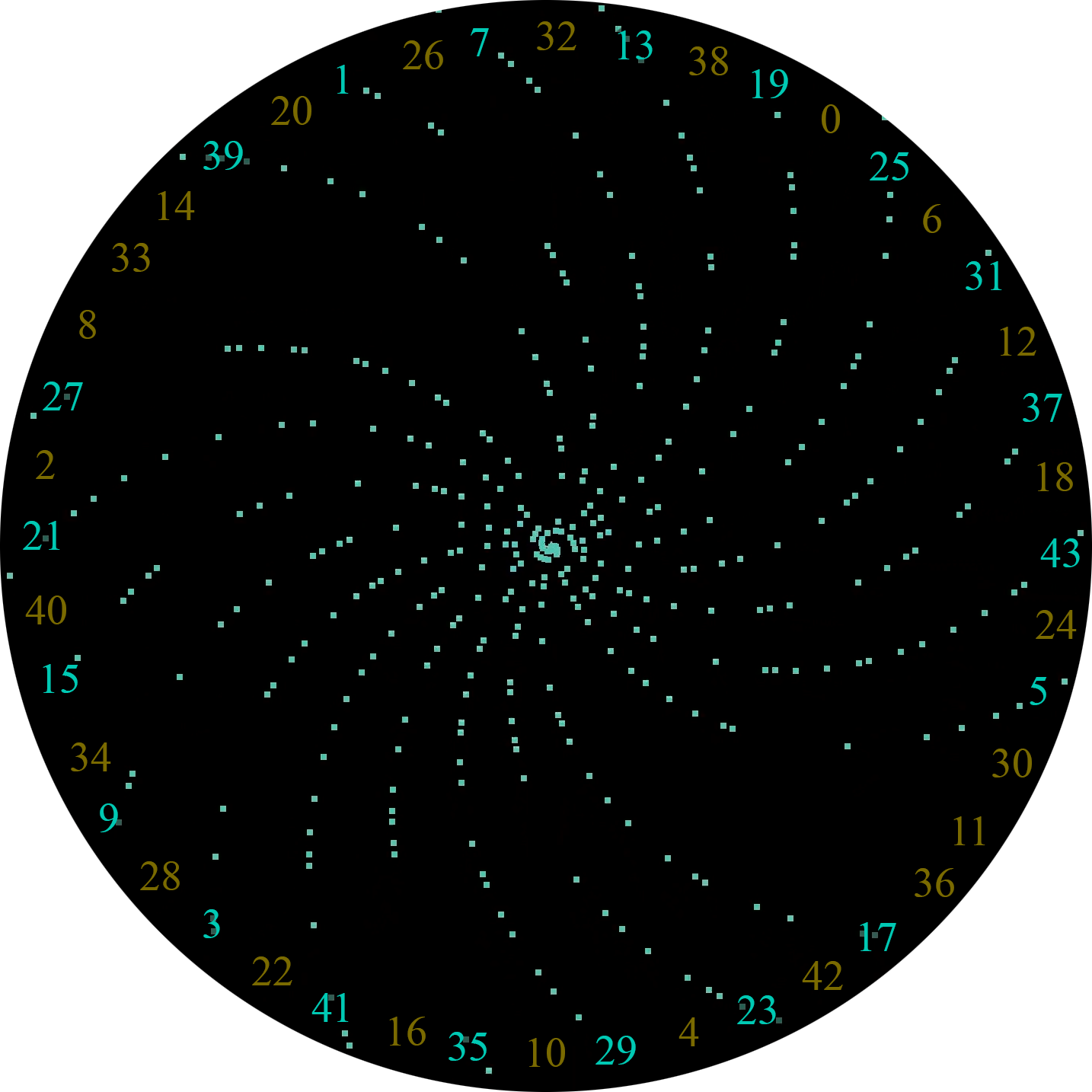

If you knock out everything except the prime numbers, it initially looks quite random. After all, primes are famous for their chaotic and difficult-to-predict behavior. But when you zoom out, you see these very clear galactic seeming spirals. What's weird is that some of the arms seem to be missing.

Zooming out even farther, those spirals give way to a different pattern: these many different outward rays. Those rays seem to come mostly in clumps of 4, but with an occasional gap here and there, like a comb missing some teeth

The question, naturally, is what on Earth is going on here? Where do these spirals come from, and why do we instead get straight lines at a larger scale? You could be more quantitative and count that there are 20 spirals, and up at the larger scale if you patiently went through each ray you'd count a total of 280. But of course, this just raises further questions on where these numbers come from, and why they'd arise from primes.

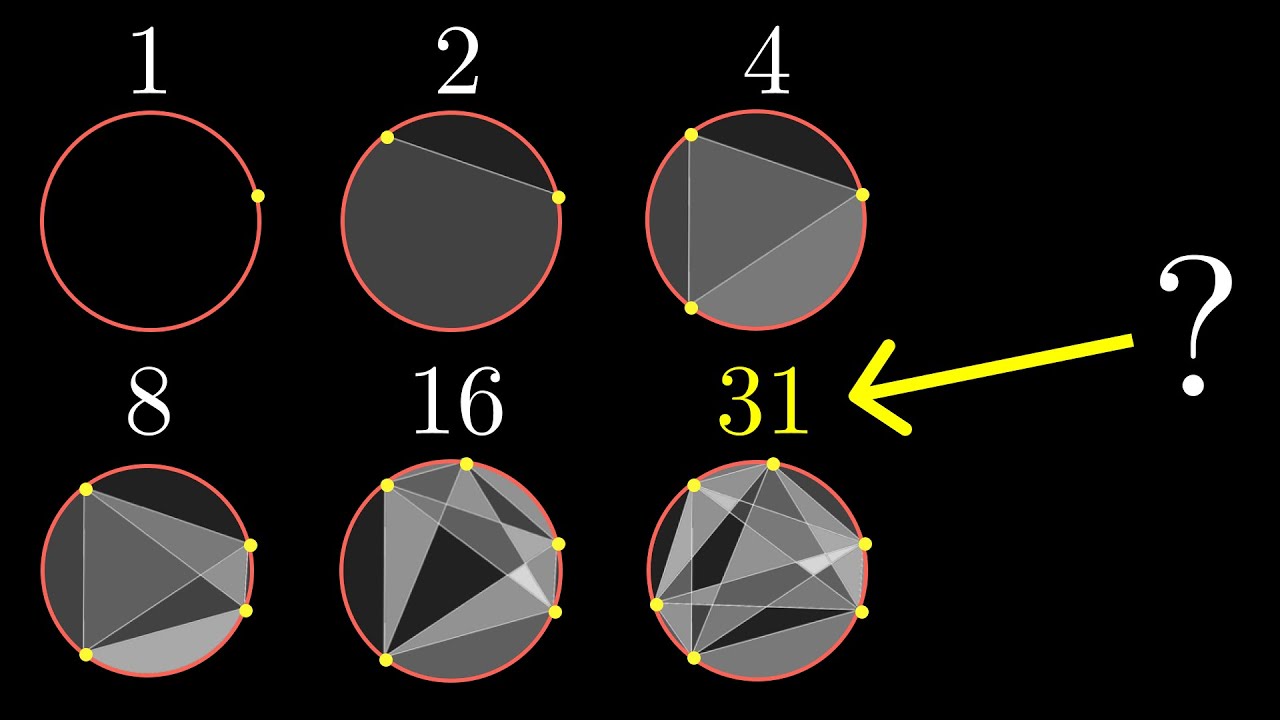

These patterns are certainly beautiful, but they don't have a hidden, divine message about primes. I should say upfront, the fact the math exchange question jumped right into primes makes the puzzle a bit misleading. If you look at all the whole numbers, not just the primes, you see very similar spirals.

They're much cleaner, and there are now 44 of them, but it means the question of where the spirals come from is, perhaps disappointingly, completely separate from what happens when we limit our view to primes.

Before you get too disappointed, the question of why we see spirals at all is still a great puzzle. And even if primes don't cause the spirals, asking what goes on when you filter for primes does lead you to one of the most important theorems on the distribution of prime numbers, known as Dirichlet's theorem.

Ingredients for a Spiral PI

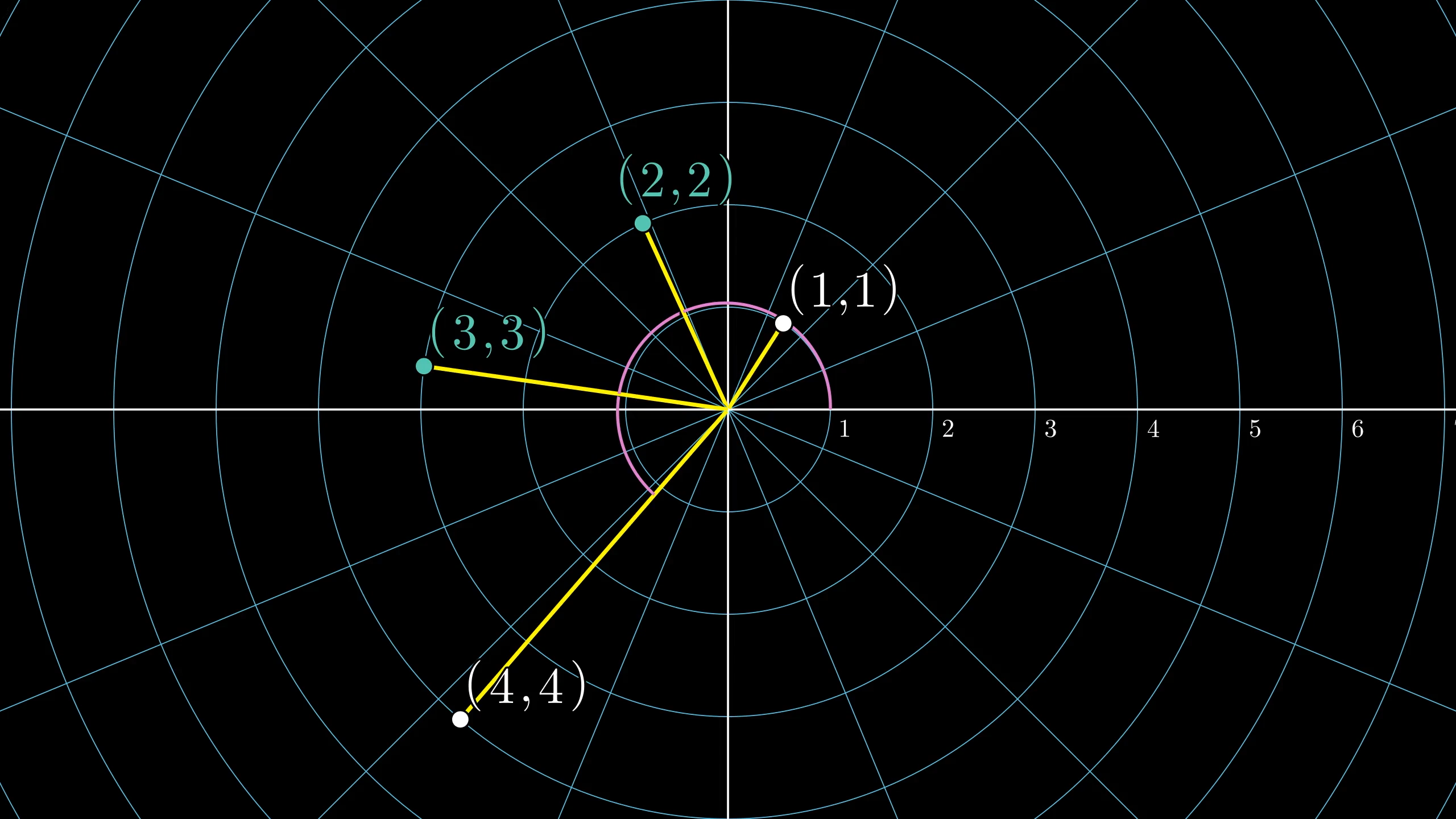

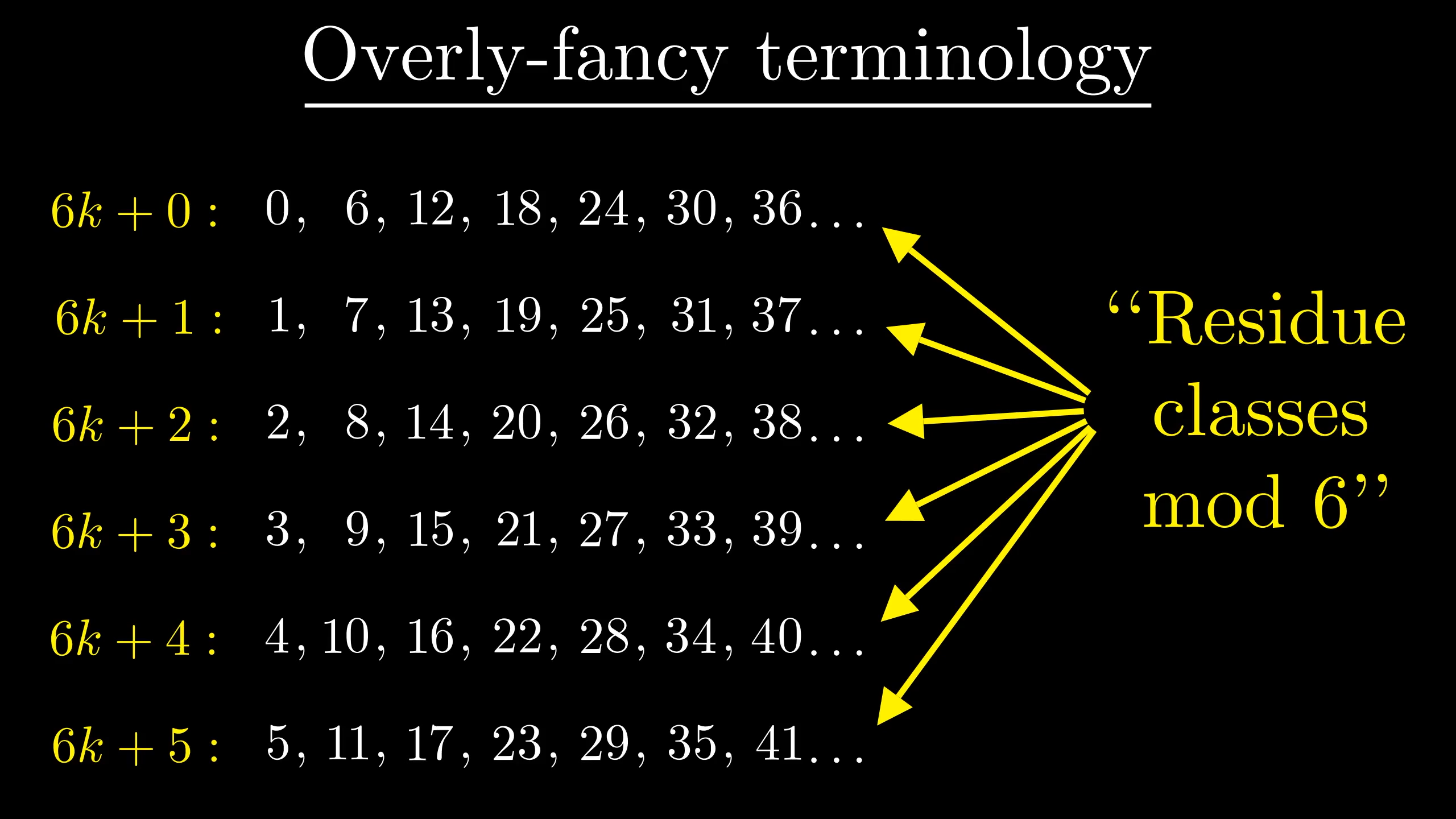

To start, did you notice that at a much smaller scale there were 6 little spirals? This offers a good starting point to explain what's happening in the two larger patterns. Notice how all the multiples of 6 form one of the arms of this spiral. Then the next one is every number one above a multiple of 6, and the one after that includes all numbers two above a multiple of 6, and so on. Why is that?

Remember, each step forward in the sequence involves a turn of one radian, so when you count up by 6, you've turned a total of 6 radians, which is a little less than , a full turn. So every time you count up 6, you've almost made a full turn, it's just a little less. Another six steps, a slightly smaller angle, six more, smaller still, and so on, with this angle changing gently enough to give the illusion of a single curving line.

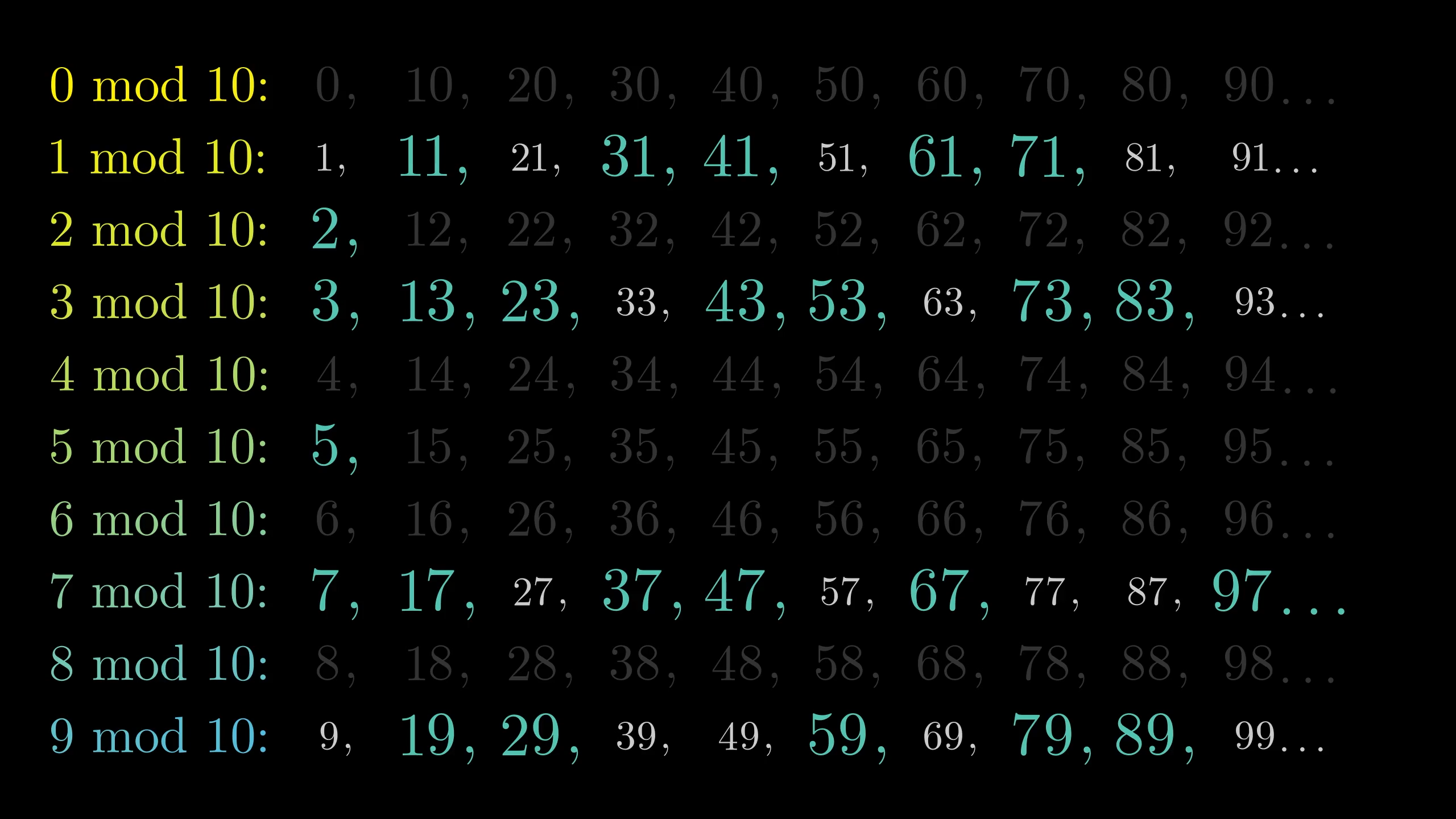

If you limit the view to prime numbers, all but two of these spiral arms go away. Think about it… a prime number can't be a multiple of 6. It also can't be 2 above a multiple of 6, unless it's 2, nor can it be 4 above a multiple of 6, since all those are even numbers. It also can't be 3 above a multiple of 6 (unless it's the number 3 itself) since all those numbers are divisible by 3.

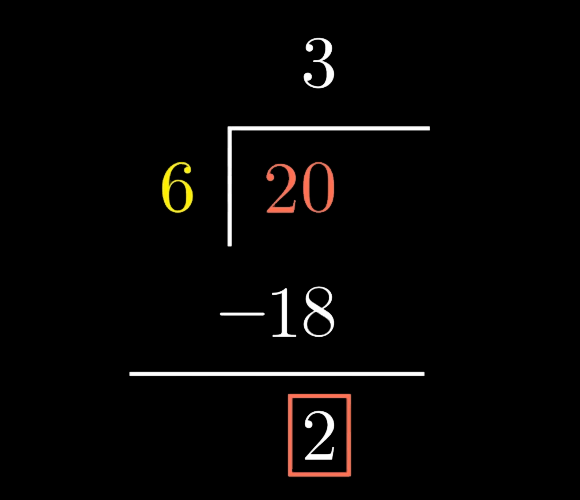

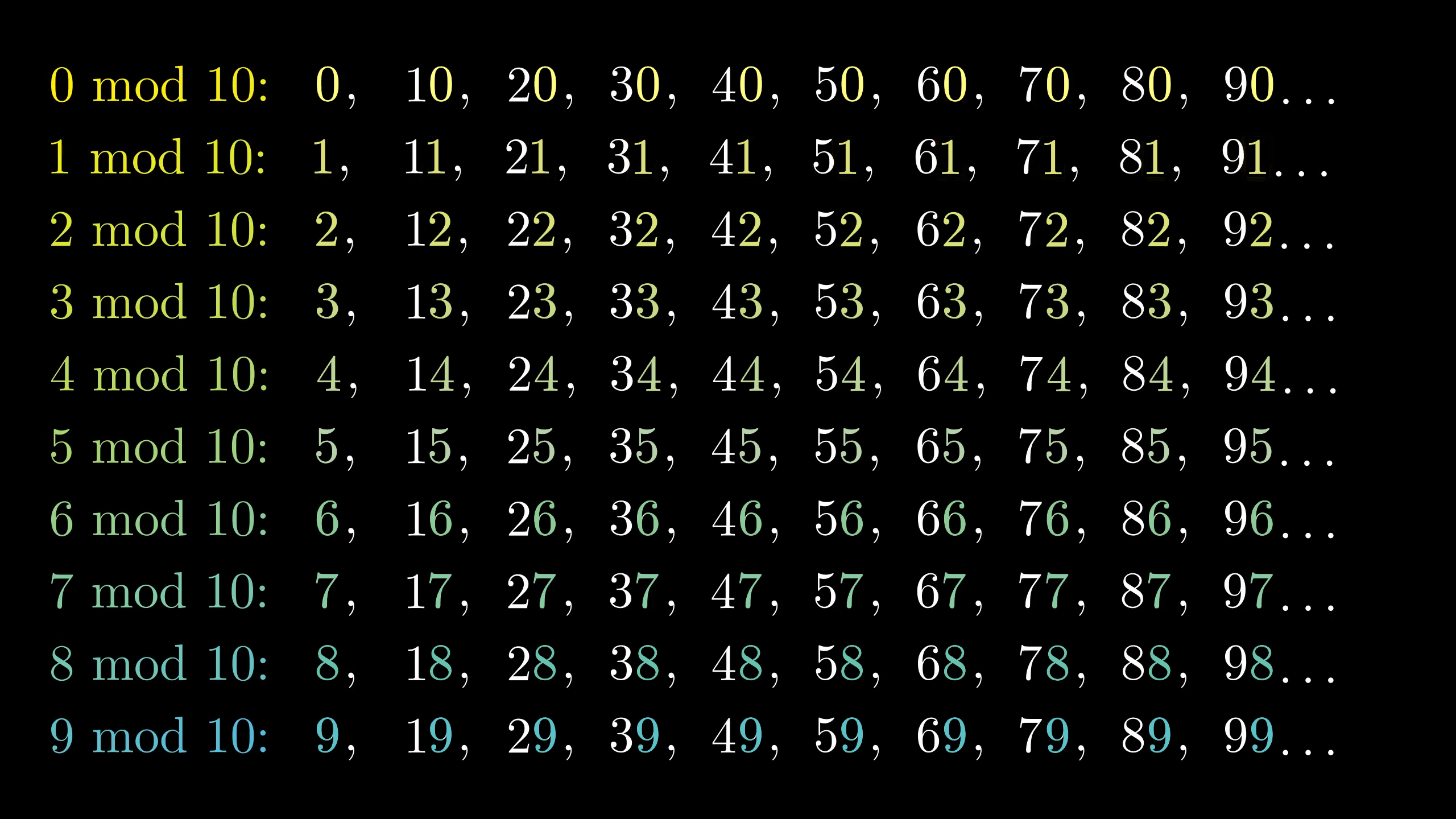

While we're in this simpler context, let me introduce some terminology that mathematicians use. Each of these sequences where you're counting up by 6 is called a "residue class, mod 6". The word "residue" in this context is a fancy way of saying "remainder", and mod means something like "from division by". The label "residue class mod 6" means "a set of remainders from division by 6."

For example, 6 goes into 20 three times, with a remainder of 2, so 20 has a "residue of 2 mod 6".

Together with all other numbers leaving a remainder of 2 when the thing you divide by is 6, you have a full "residue class". I know that sounds like the world's most pretentious way of saying "everything 2 above a multiple of 6", and it is! But this is the standard jargon, and it is handy to have some words for the idea.

So in the lingo, each of these spiral arms corresponds to a residue class mod 6, and the reason we see them is that 6 is close to ; turning 6 radians is almost a full turn. And the reason we only see two of them when filtering for primes is that all prime numbers are either 1 or 5 above a multiple of 6 (with the exceptions of 2 and 3). The other four residue classes hold numbers which are either even or divisible by 3.

Which residue class mod 6 does the number 381 belong to?

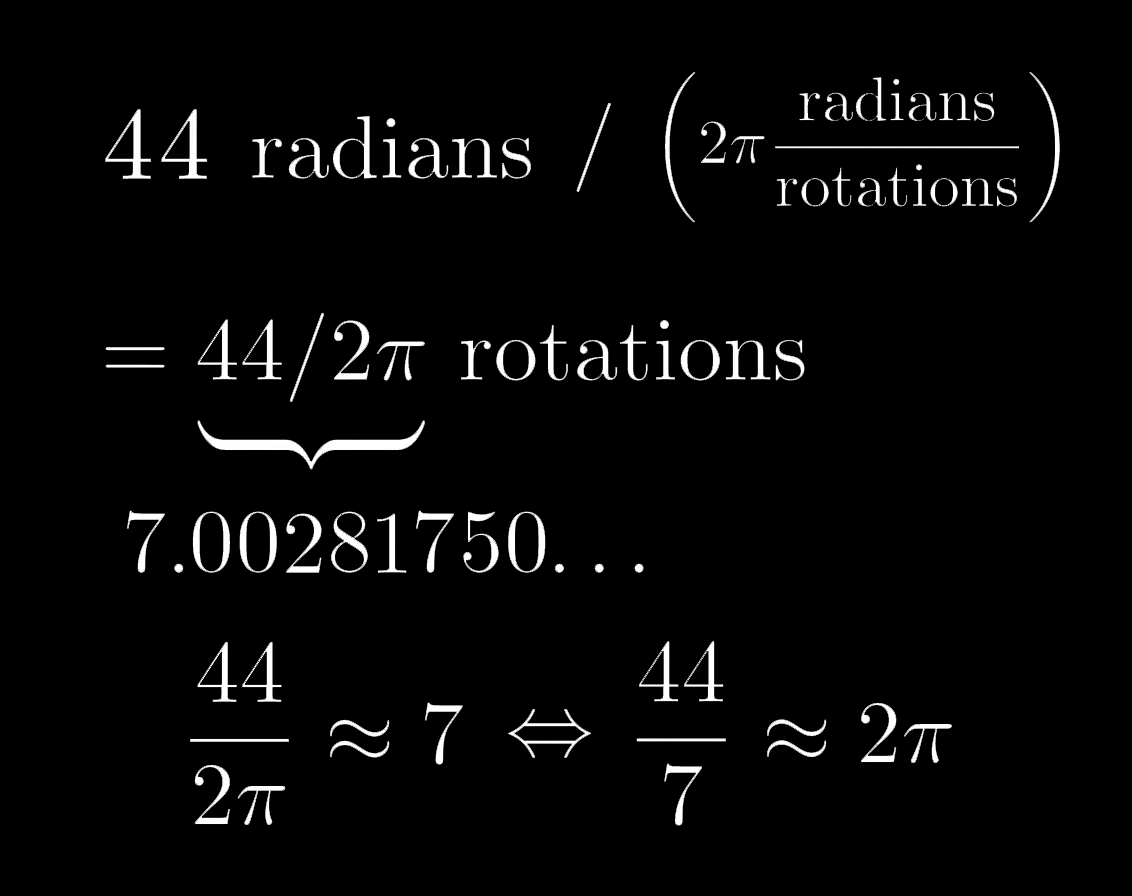

With that as a warmup, let's think about the larger scale patterns. In the same way that 6 steps were close to a full turn, taking 44 steps is very close to a whole number of turns.

Since there are radians per rotation, taking 44 steps gives a total of rotations, which comes out to be just barely above 7 full turns. You could also write this by saying is a close approximation for , which some of you may better recognize as the famous approximation for .

So if you count by multiples of 44 in the diagram, each point has almost the same angle as the last, just a little bit bigger, so as you continue on with more and more we get this gentle spiral as that angle increases very slowly. All of the numbers 1 above a multiple of 44 make a similar spiral, but rotated one radian counterclockwise. Same for everything 2 above a multiple of 44, and so on.

To phrase it with the fancier language, each of these spiral arms is a residue class mod 44. And maybe now you can tell me what happens when we limit the view to prime numbers.

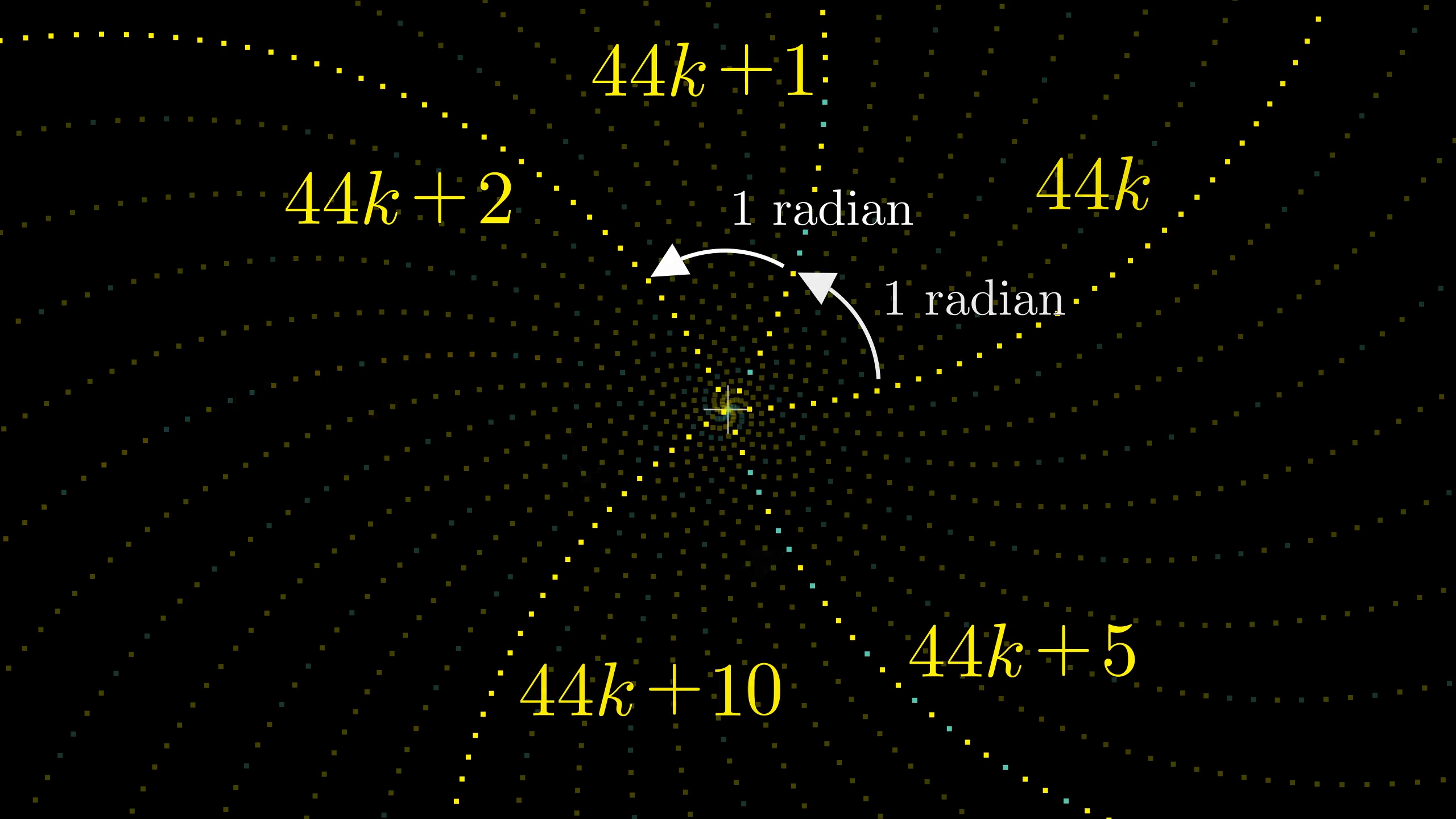

Prime numbers cannot be a multiple of 44, so that arm won't be visible. Similarly, you won't see primes 2 above a multiple of 44, or 4 above, and so on, since all those residue classes have nothing but even numbers.

Of the residual classes mod 44, only 20 arms are visible when filtering for primes.

Likewise, any multiple of 11 can't be prime, except for 11 itself, so the spiral of numbers 11 above a multiple of 44 won't be visible, and neither will the spiral of number 33 above a multiple of 44. Each spiral we're left with is a residue class that doesn't share any factors with 44. Within each of these spiral arms that we can't reject out of hand, the primes seem to be somewhat randomly distributed, a fact I'd like you to tuck away for later.

This is another good chance for a side note on jargon mathematicians use. What we care about here are all the numbers between 0 and 43 that don't share any prime factors with 44, right? The ones which aren't even, and aren't divisible by 11. Two numbers that don't share any factors like this are called "relatively prime", or "coprime".

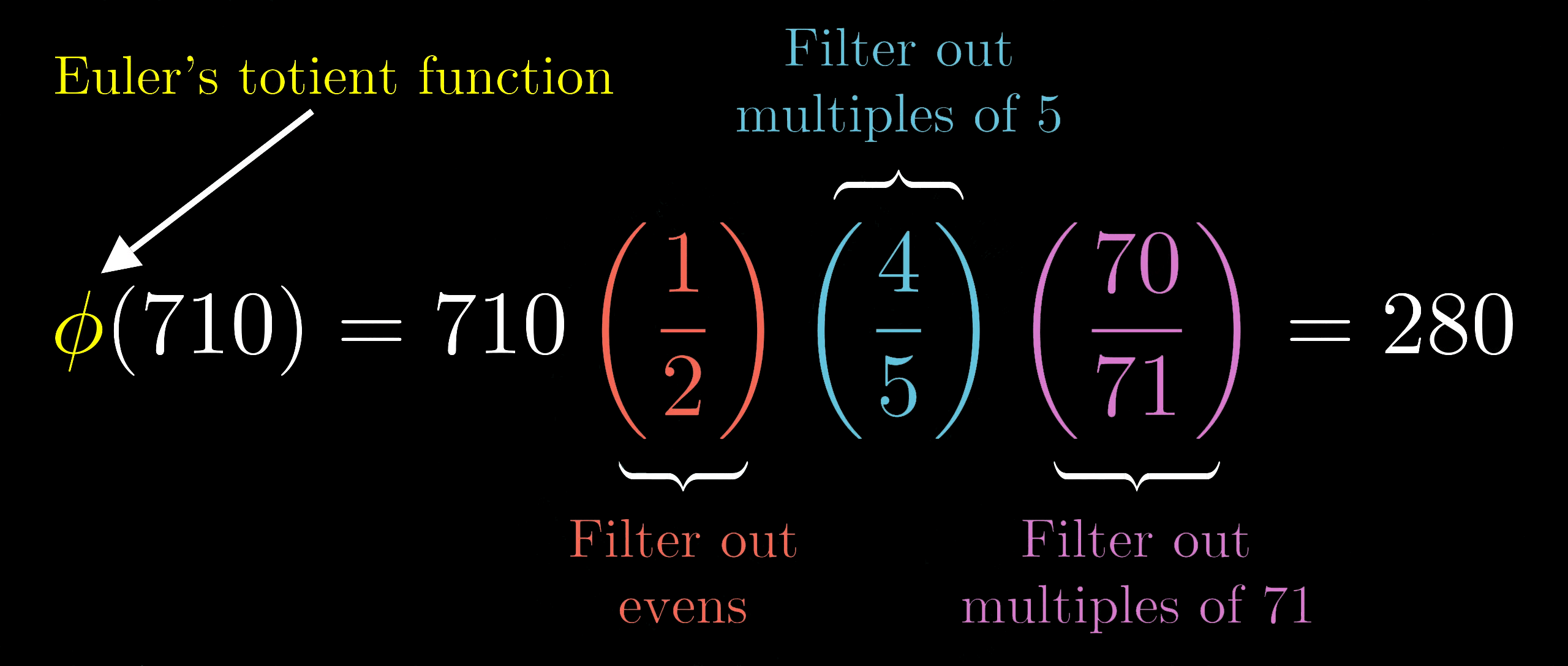

You can count that there are 20 numbers between 1 and 44 coprime to 44, a fact that a number theorist would compactly write as:

The greek letter phi, , here refers to "Euler's totient function" (yet another needlessly fancy word). It is defined to be the number of integers from 1 up to which are coprime to . More obscurely, these numbers are sometimes called the "totatives" of .

In short, what the user on math exchange was seeing are two unrelated pieces of number theory illustrated in one drawing: The first is that is a close rational approximation to , which results in residue classes mod 44 being cleanly separated out. The second is that many of these residue classes contain either 0 or 1 primes, so won't show up, while primes do show up plentifully enough in the remaining 20 residue classes to make these spiral arms visible.

Perhaps now you can predict what's going on at a larger scale. Just as 6 radians is vaguely close to a full turn, and 44 radians is quite close to 7 full turns, it so happens that 710 radians is extremely close to a whole number of turns.

Specifically, 710 radians is rotations, which works out to be 113 point zero zero zero zero zero nine. This is the same thing as saying that is a very close rational approximation to , which may be recognizable as the approximation of .

If you want to understand where rational approximations like this come from, and what it means for something like this one to be "unusually good", take a look at this great mathologer video.

What this means is that if you move forward by steps of 710, the angle of each new point is almost exactly the same as the last, only microscopically bigger. Even very far out, such a sequence appears to be on a straight line. And of course, the other residue classes mod 710 also form nearly-straight lines.

710 radians is so close to a whole number of revolutions that the 710k residue class appears to be almost exactly on the x-axis.

With all 710 of them, and only so many pixels on the screen, it can be a bit hard to make them out. So in this case, it's actually easier to see once we limit the view to primes, where you don't see many of these residue classes.

Which quadrant would the class show up in if it were on the above graph?

In reality, with a little further zooming, you can see that there is actually a gentle spiral to these, but the fact that it takes so long to become prominent is a wonderful illustration, maybe the best illustration I've seen, for just how good an approximation is for .

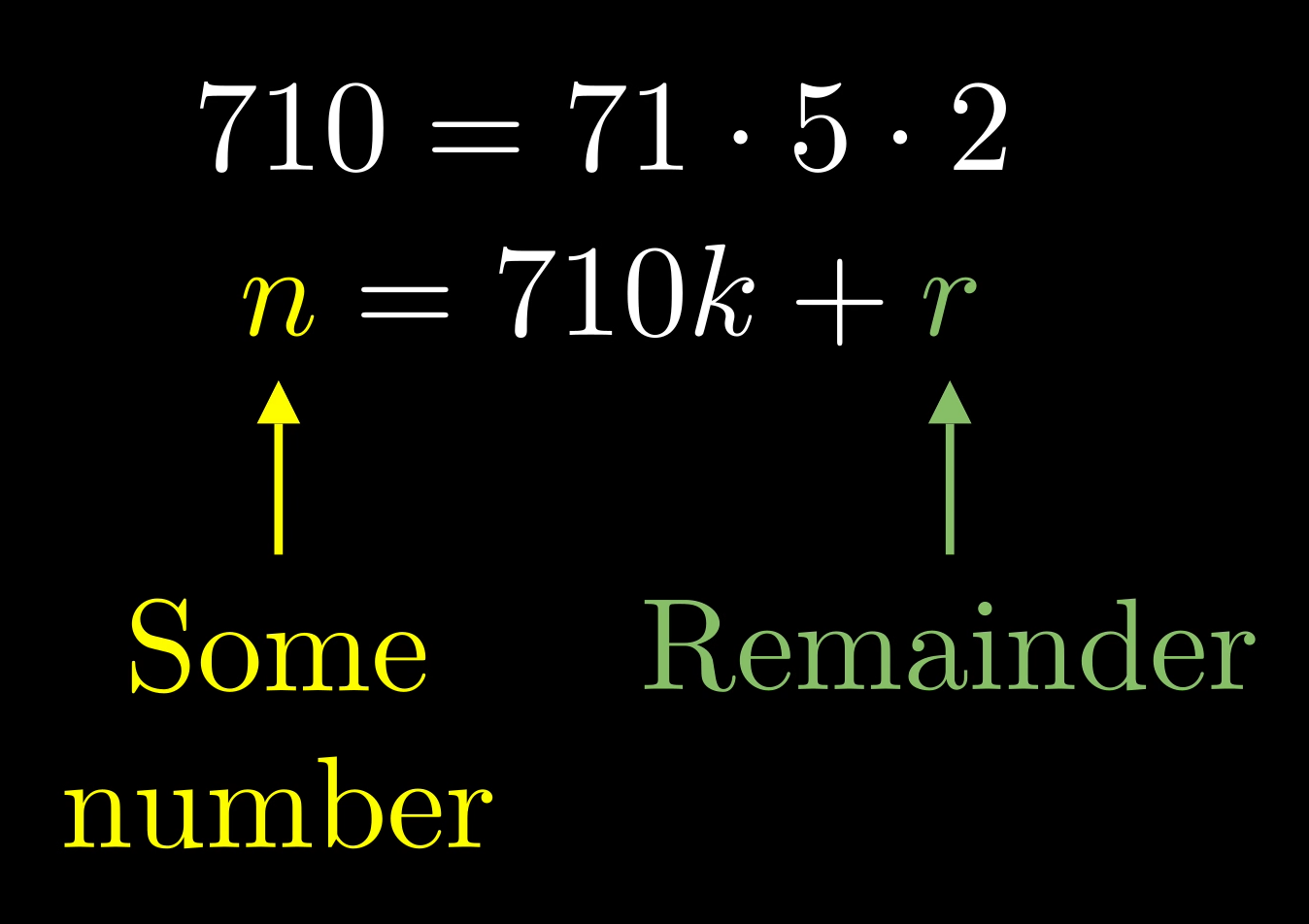

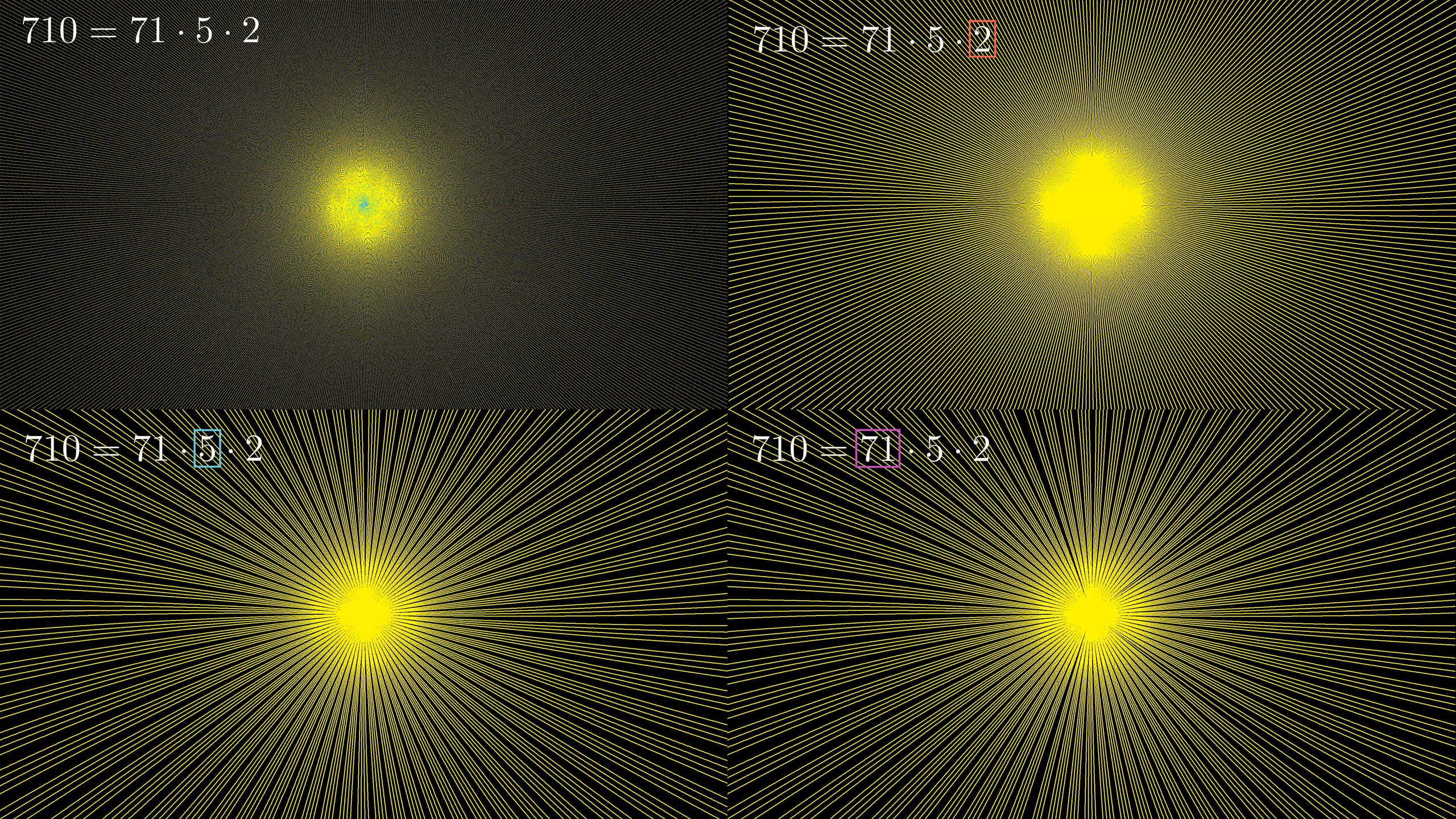

To understand what happens when we filter for primes, it's entirely analogous to what we did before. The factors of 710 are 71, 5 and 2. So if the remainder is divisible by any of those, then so is your number.

When you pull up all of the residue classes with odd numbers, it looks like every other ray in our crowded picture. Of those which remain, these are the ones divisible by five, which are nice and evenly spaced at every fifth line. Notice, the fact that primes never show up in these is what explains the pattern of these lines coming in clumps of four. And of those remaining, these four residue classes are divisible by 71, so the primes won't show up there. This explains why some of the clumps of four seem to be missing a tooth.

The top left plots all of the residue classes. Each successive plot continues to filter for the prime factors of 710.

So if you were wondering where the number 280 came from earlier, it comes from counting how many numbers from 1 to 710 don't share any factors with 710; these are the ones that we can't rule out for including primes based on some obvious divisibility consideration.

This of course doesn't guarantee that any particular one will have prime numbers, but when you look at the picture, it actually seems like the primes are pretty evenly distributed among all these remaining classes, wouldn't you agree?

Every color in the rainbow can be seen, showing that every remaining residue class has about the same density of primes.

Dirichlet's Theorem

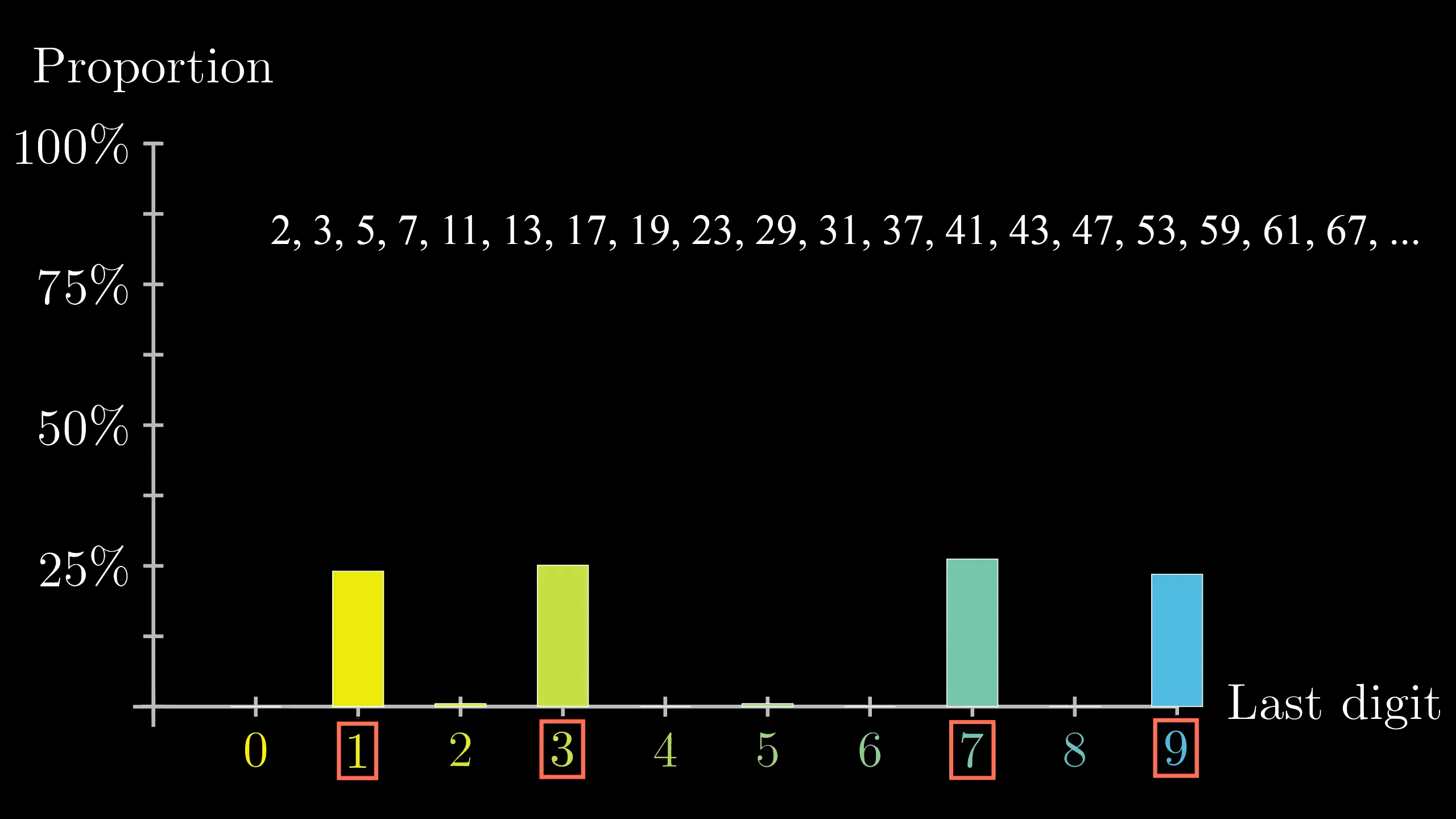

That last point actually relates to a fairly deep fact, known in number theory as "Dirichlet's theorem". To take a simpler example than residue classes mod 710, think of those mod 10. Because we write numbers in base 10, this is the same thing as grouping numbers together by what their last digit is. So numbers ending with a digit 0 form one residue class, numbers ending with a digit 1 form another, and so on.

Other than 2, prime numbers can't have an even number as their last digit, since that means they're even. Similarly any prime bigger than 5 can't end in a 5. There's nothing surprising there, primes bigger than 5 must end in a 1, 3, 7 or 9.

How are the primes distributed between the residue classes 0 mod 2 and 1 mod 2?

All of the primes except 2 would be in the 1 mod 2 class, because it contains all the odd numbers. The 0 mod 2 class has all the even integers, and the only even prime is 2.A much more nuanced question is how the primes are distributed among the remaining four groups. Let's make a quick histogram, counting through each prime, and showing what proportion of primes we've seen so far have a given last digit. What do you predict will happen as we go through more and more primes?

The 2nd and 5th residue class's proportion go to zero as more primes are added to the histogram.

As we add more primes to the histogram, it seems like a pretty even spread between these four classes, about 25% for each. Maybe that's what you'd expect. After all, why would primes show any preference for one last digit over another? But it's highly nonobvious how you would prove such a thing. Or for that matter, how do you rigorously phrase what it is you want to prove?

A mathematician might go about it like this: If you look at all the prime numbers less than for some large , and consider what fraction of them are, say, one above a multiple of 10, that fraction should approach as approaches infinity.

Likewise for all the other allowable residue classes 3 and 7 and 9. And of course, there's nothing special about 10, a similar fact should hold for other numbers.

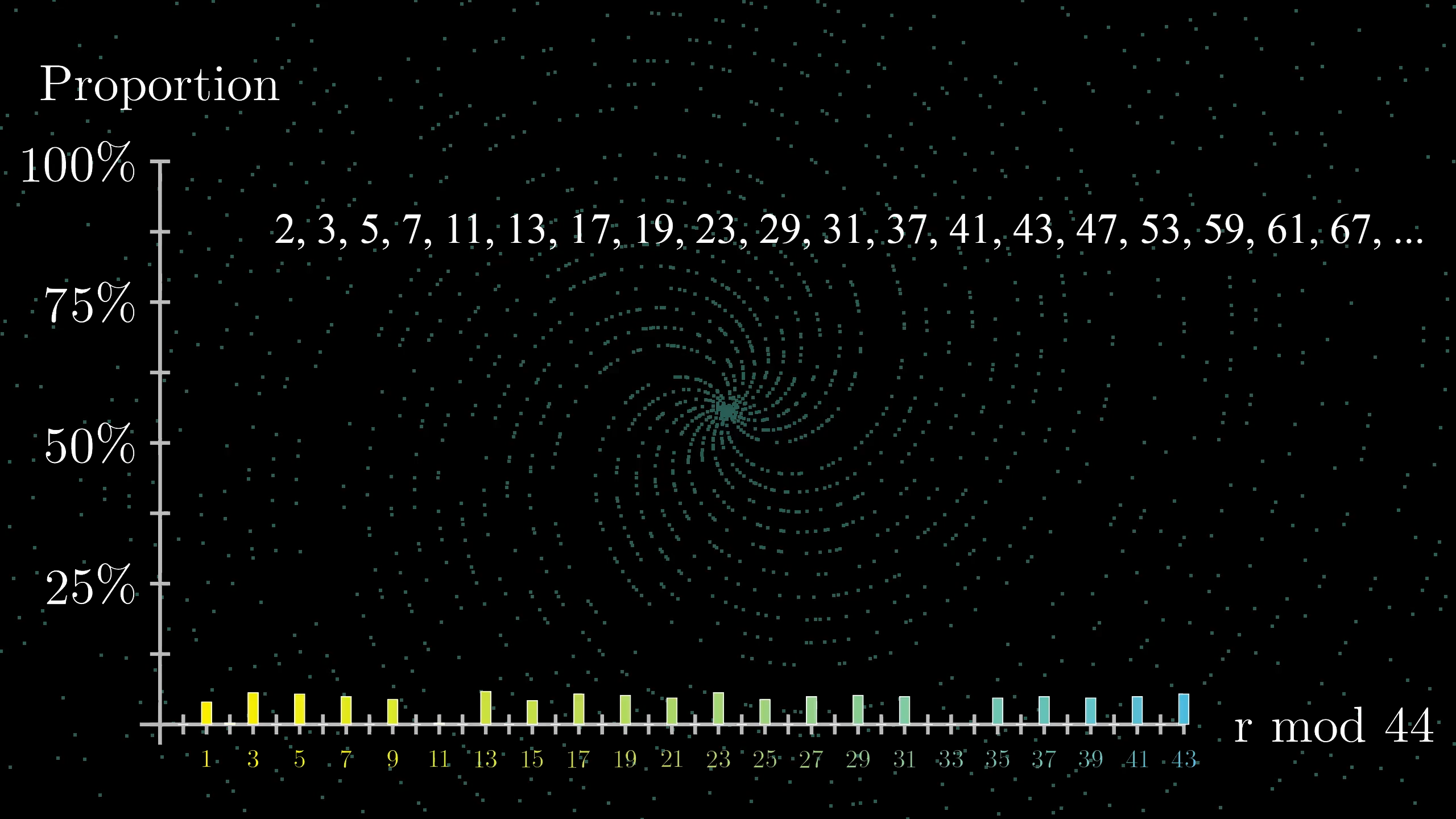

Consider our old friends the residue classes mod 44. For example, let's make a similar histogram, showing what proportion of the primes show up in each one. Again, as time goes on, we see an even spread between the 20 allowable residue classes, meaning each spiral arm from our diagram has about the same number of primes as the others. Again, perhaps this is what you'd expect, but it's shockingly hard to prove.

All of the even classes and 11 + 33 quickly go to zero, just like the missing arms of the spiral.

How many primes will be in the 71st histogram bin for the larger spiral pattern (r mod 710)?

Just one! 71 is one of the prime factors of 710, so after 71 is put in the bin, no other primes will follow.The histograms give a pretty good illustration of what we mean by an even distribution, but it might be enlightening to see how it would be phrased in a math text, fancy jargon and all. It's essentially what we just saw for 10, only more general. Again, look at all the primes up to some bound , but instead of asking what proportion of them have a residue of, say, 1 mod 10, you ask what proportion have a residue of mod , where is any number, and is anything coprime to .

Remember, to be "coprime" means they don't share factors bigger than 1. Instead of approaching , that proportion approaches , where is that special function I mentioned earlier that gives the number of residues coprime to . For example:

In case this is too clear for the reader, you might even see it buried in more notation, where this denominator and numerator are written with a special prime counting function, which, rather confusingly, has the name ; totally unrelated to the number .

We're running out of symbols!

What does this equation equal?

It turns out to be rather difficult to prove that the primes are evenly distributed among residue classes like this. In 1837, Dirichlet published a result which is very close to this, but he used a slightly different definition of density. Instead of simply counting the primes up to a certain threshold, it involves looking at all primes and adding up the values for some real number . Specifically, in his notion, here's how the density of primes which are mod would look:

This looks more complicated, but based on the approach Dirichlet used this turns out to be easier to wrangle with mathematically. The real significance of his result, though, was that it was the first time anyone could show that there are infinitely many primes in any residue class (assuming and are coprime).

For example, imagine you were asked to prove that infinitely many primes end in the digit 1, and the way you do it is by showing that a quarter of all primes end in a 1. Together with the fact that there are infinitely many primes, which we’ve known since Euclid, this gives a much stronger statement, and a much more interesting one.

So how did Dirichlet prove it? Well… it’s way more involved than what would be reasonable to show here, but one interesting fact worth mentioning is that it relies heavily on complex analysis, which is the study of doing calculus with functions whose inputs and outputs are complex numbers. That may seem surprising, given that prime numbers seem unrelated to the continuous world of calculus, much less when complex numbers end up in the mix. But since the early 19th century, that’s absolutely par for the course when it comes to understanding how primes are distributed.

This isn’t just antiquated technology. Understanding the distribution of primes in residue classes like this continues to be relevant in modern research, too. Some of the recent breakthroughs on small gaps between primes, edging towards that ever-elusive twin prime conjecture, have their basis in understanding how primes split up among these kinds of residue classes.

From Arbitrary to Important

To close things off, I want to emphasize something. In some sense, the original bit of data visualization whimsy that led to these patterns... it doesn’t matter. No one cares. There’s nothing natural about plotting in polar coordinates, and most of the initial mystery in these spirals resulted from artifacts that come from dealing with an integer number of radians.

But on the other hand, this kind of play is clearly worth it if the end result is a line of questions leading you to something like Dirichlet’s theorem, which is important, especially if it inspires you to learn enough to understand the tactics of the proof.

It’s not a coincidence that a fairly random question like this one can lead you to an important and deep fact from math. What it means for a piece of math to be important is that it connects to many other topics. So even arbitrary explorations of numbers, as long as they aren’t too arbitrary, have a good chance of stumbling into something meaningful.

Sure, you’ll get a much more concentrated dosage of important facts by going through a textbook or a course, with far fewer uninteresting dead ends. But there’s something special about rediscovering these topics on your own. If you effectively reinvent Euler’s Totient function before ever seeing it defined, or start wondering about rational approximations before learning about continued fractions, or if you seriously explore how primes are divvied up between residue classes before you’ve even heard the name Dirichlet, then when you do learn those topics, you’ll see them as familiar friends, not as arbitrary definitions.

A Challenging Exploration

As a demonstration for what it is like to explore an arbitrary path of mathematics, let's extend this problem into 3 dimensions. Spherical coordinates is a method of plotting a point in 3D space using the distance to the origin, the angle from the axis, and the angle from the axis. We can condense this formula into:

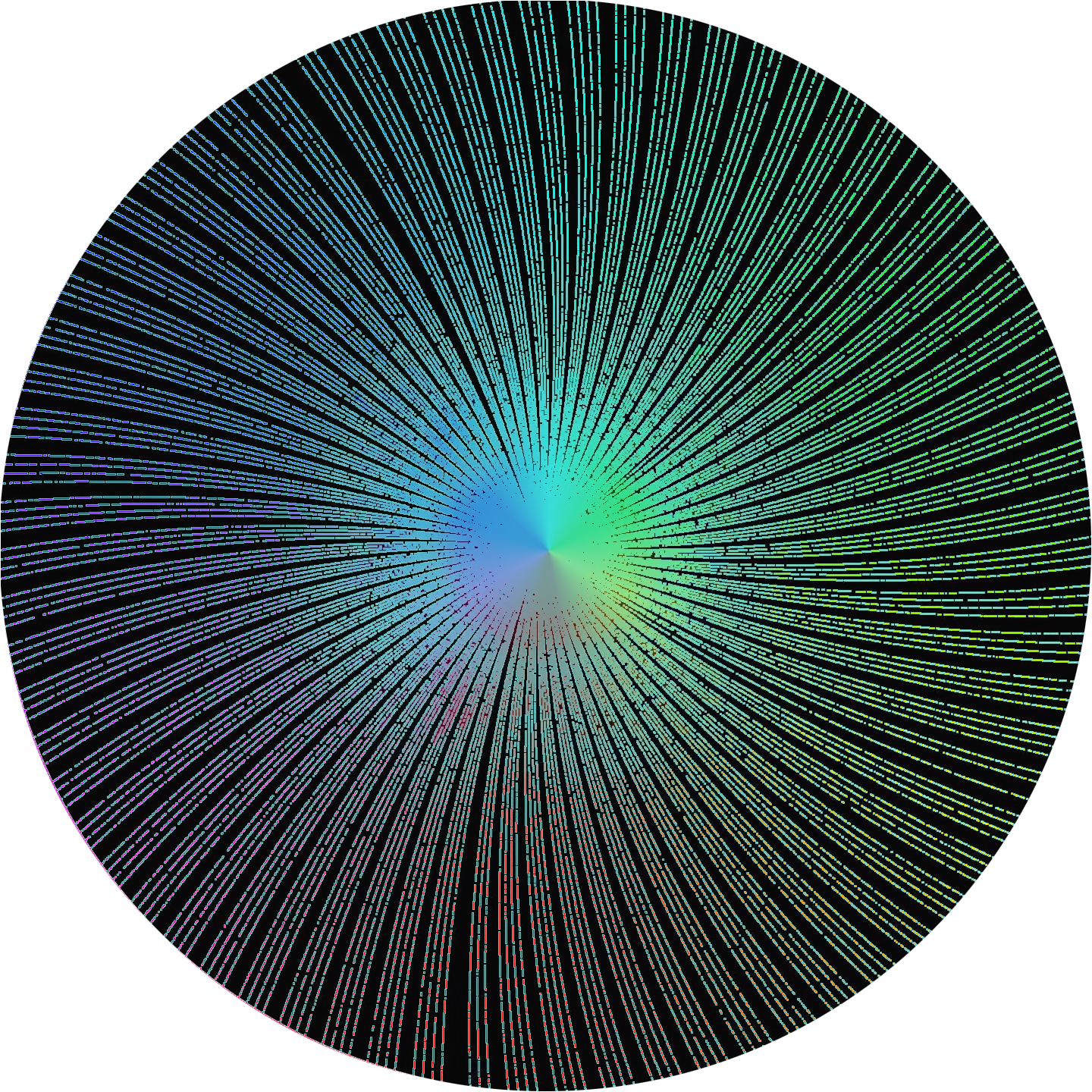

If we take the first few thousand prime numbers and plot them as in spherical coordinates, what pattern emerges?

The spiral galaxy we saw on the 2D plane is still visible, but now it looks like some type of infinity spiral where the arms of the galaxy are weaving in and out of each other. The and classes are still missing on either side of the center. The above image is actually an interactive applet, go ahead and click and drag on it to move it around.

The 2D plot gave us question like "why are there spirals?" and "why are some arms missing for primes?" The 3D plot gives us another question "why do the spirals go into an infinity pattern?" And just like the first two questions, this one is also unrelated to either of the previous questions. Take a moment to try and explain why this shape appears in spherical coordinates. I recommend to explore this new prompt with the math community in the comments below, what important topics arise from looking at this arbitrary choice? As you continue your journey into mathematics, keep in mind that sometimes a puzzle should be broken down into simpler components which are easier to deal with individually.

Relation to Ulam Spirals

There’s a great Numberphile video some of you may have seen entitled prime spirals, in which James Grimes describes a similar, but distinct, pattern with primes. If you haven’t seen it, I’d recommend taking a look. The idea is to write out all numbers in a grid, starting from the center, and spiraling out while circling all the primes. The pattern you get is called an “Ulam Spiral,” named after Stanislaw Ulam who first noticed this while doodling during a boring meeting.

What you find in the zoomed out pattern is a bias towards certain stripes. In our example, the spirals and rays corresponded to certain linear functions, things like , or , where you plug in some integer for . The Ulam Spiral pattern highlighted in the Numberphile video is showing something one step more complicated, which is how certain quadratic functions seem to have more primes than others. There’s an analog to Dirichlet’s theorem, known as the Chebotarev density theorem, laying out exactly how dense you expect primes to be in certain polynomial patterns like these. Again, the details are a bit too technical for the scope here. The point, though, is that not only do primes have plenty of patterns within them, but mathematicians also understand many of those patterns quite well, despite the reputation primes have of being impenetrably complicated.

Thanks

Special thanks to those below for supporting the original video behind this post, and to current patrons for funding ongoing projects. If you find these lessons valuable, consider joining.