The unexpectedly hard windmill question (2011 IMO, Q2)

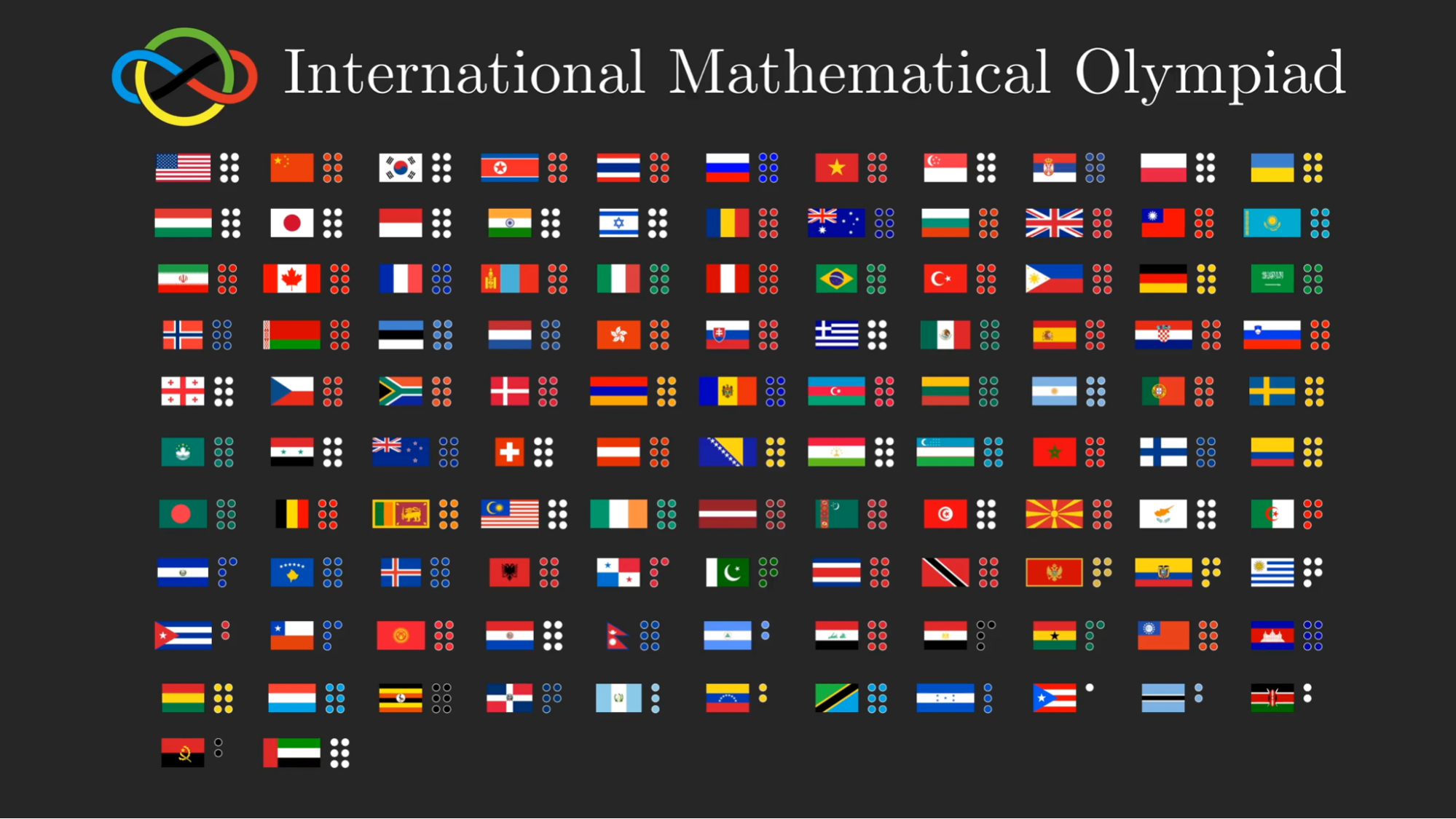

The International Math Olympiad (IMO)

Every year, more than 100 countries send 6 of their brightest teenagers, or the occasional pre-pubescent prodigy, to represent them in the International Math Olympiad, commonly known as the IMO.

Considering that each country has its own elaborate system of contests leading to their choice of 6 representatives, the IMO stands as the culminating symbol for the surprisingly expansive and wonderful world which is contest math.

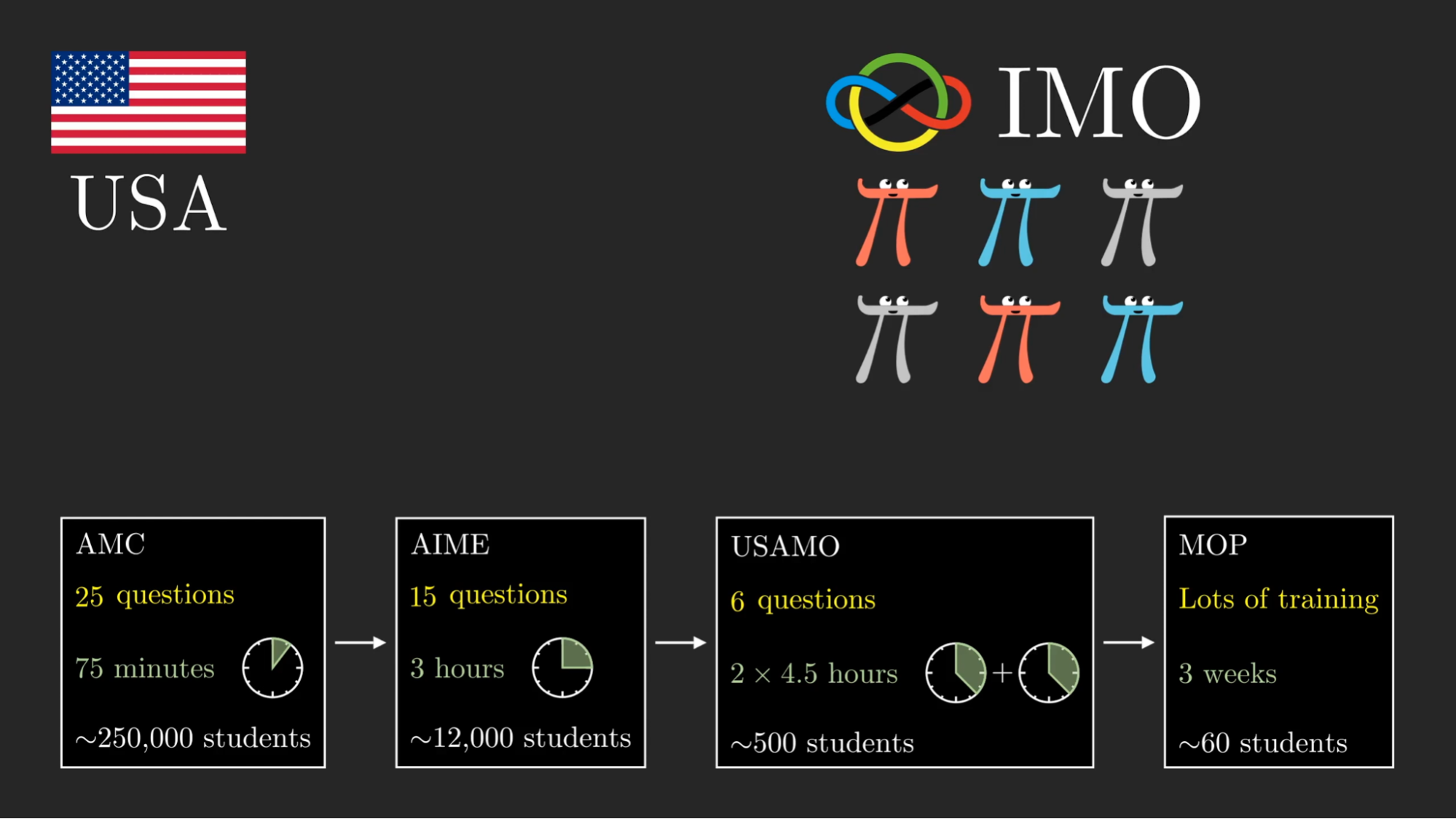

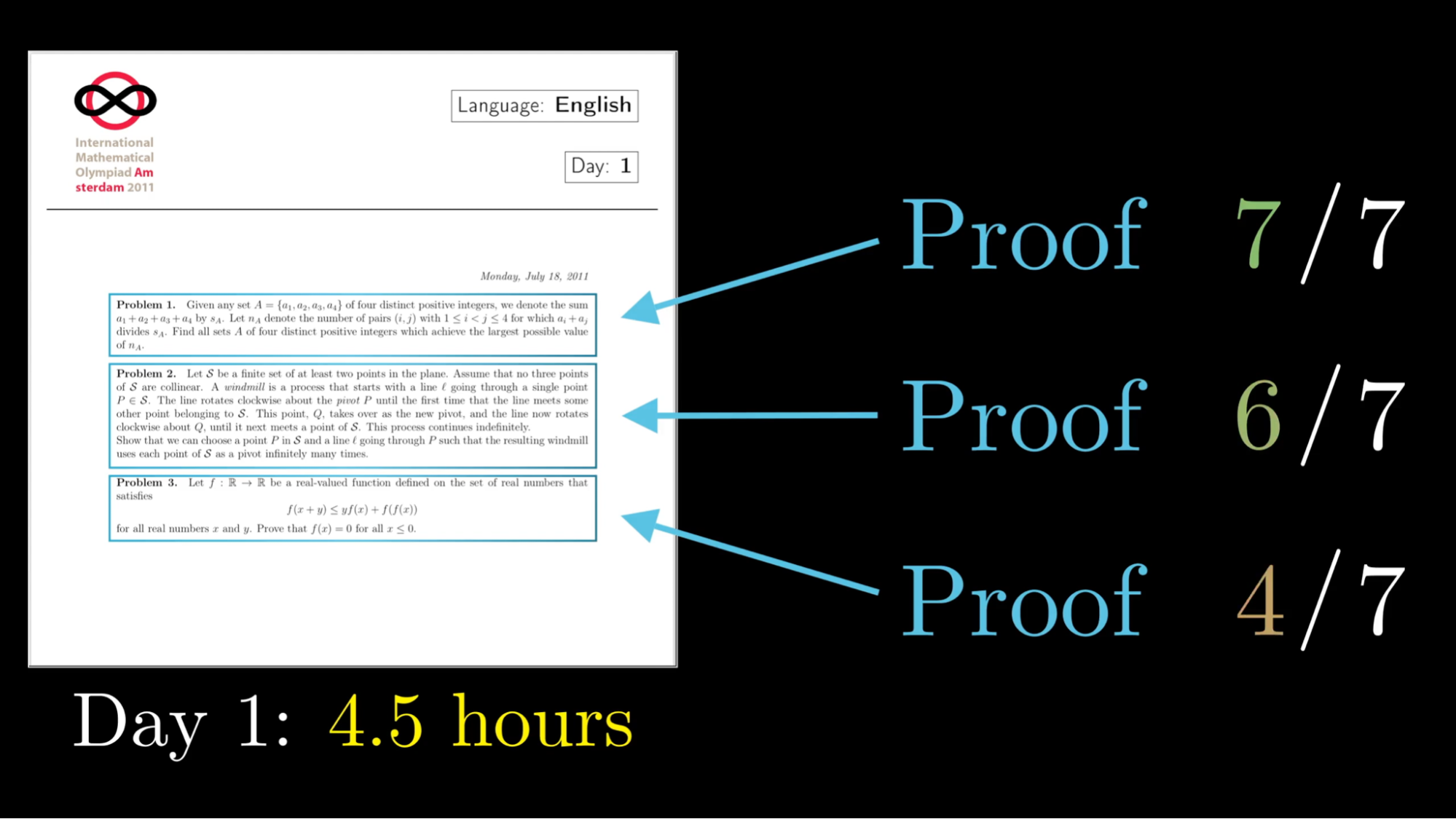

The contest is essentially a test, split over two days, with three questions given over four and a half hours each day. The questions are all proofs, meaning you don’t simply find some numerical answer, you have to discover and articulate a rigorous line of reasoning to answer each difficult question, and they are scored on a scale from 0 to 7.

Of interest to us today is the one from 2011, with 563 total participants representing 101 countries. Out of these participants, only one, Lisa Saurmann from Germany, got a perfect score. The only thing standing between the next two runners up and a perfect score that year was problem #2. This problem is beautiful, and despite evading many of the world’s best mathematicians of their age, the solution is something which anyone watching this video can understand.

The problem

Let be a finite set of at least two points in the plane. Assume that no three points of are collinear. A windmill is a process that starts with a line going through a single point in . The line rotates clockwise about the pivot until the first time that the line meets some other point belonging to . This point, , takes over as the new pivot, and the line now rotates clockwise about , until it next meets a point of . This process continues indefinitely. This point, , takes over as the new pivot, and the line now rotates clockwise about , until it next meets a point of . This process continues indefinitely.

So let’s begin by reading it carefully.

Let be a finite set of at least two points in the plane

As you read a question it’s often helpful to start drawing out an example for yourself.

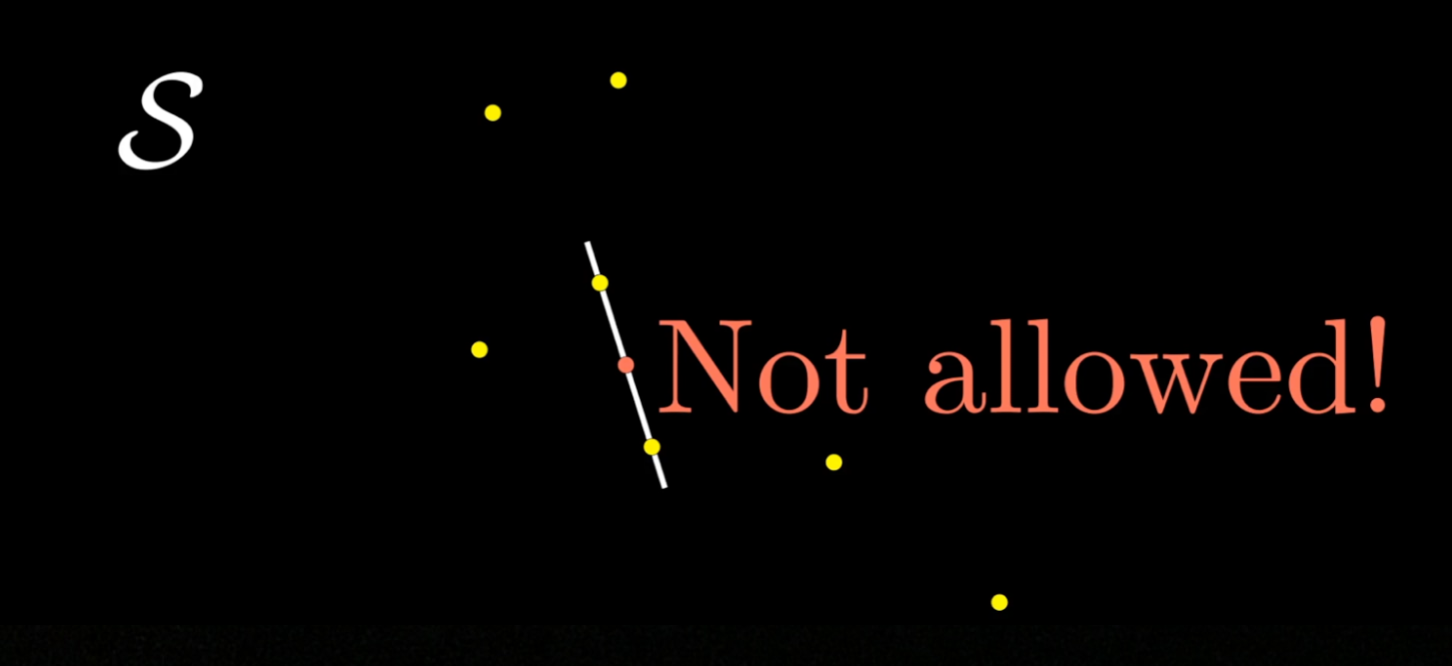

Assume that no three points of are collinear

In other words, you never have three points that line up. So you can probably predict that the problem involves drawing lines here in a way where three points on one line would mess things up.

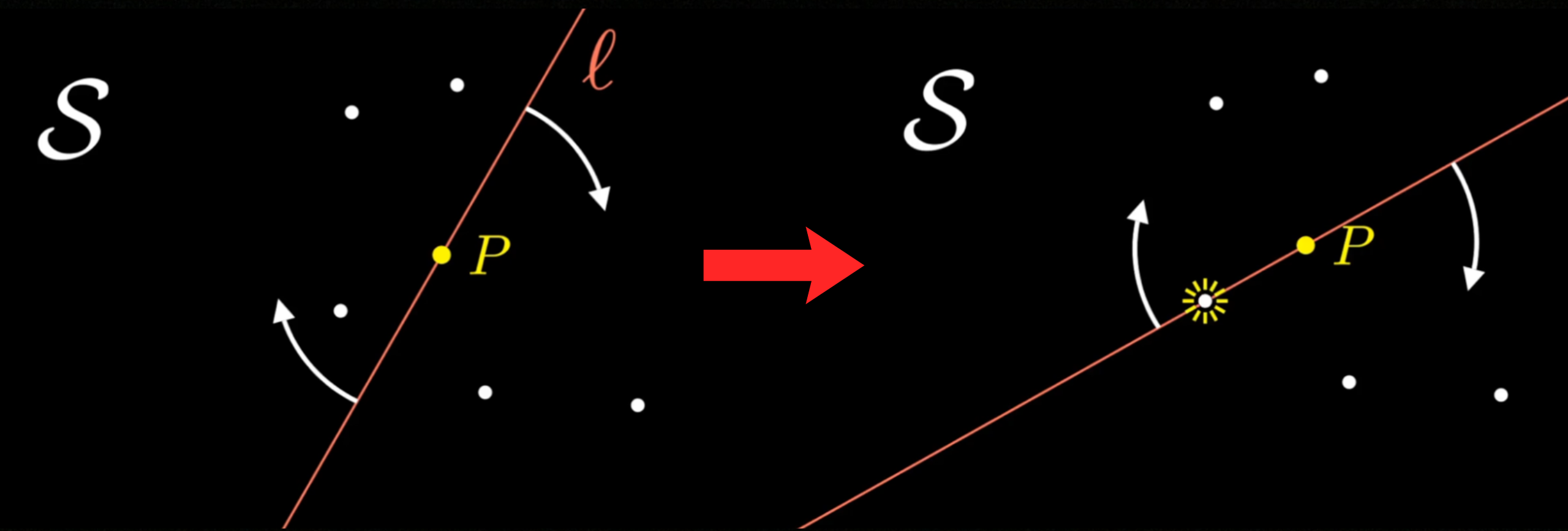

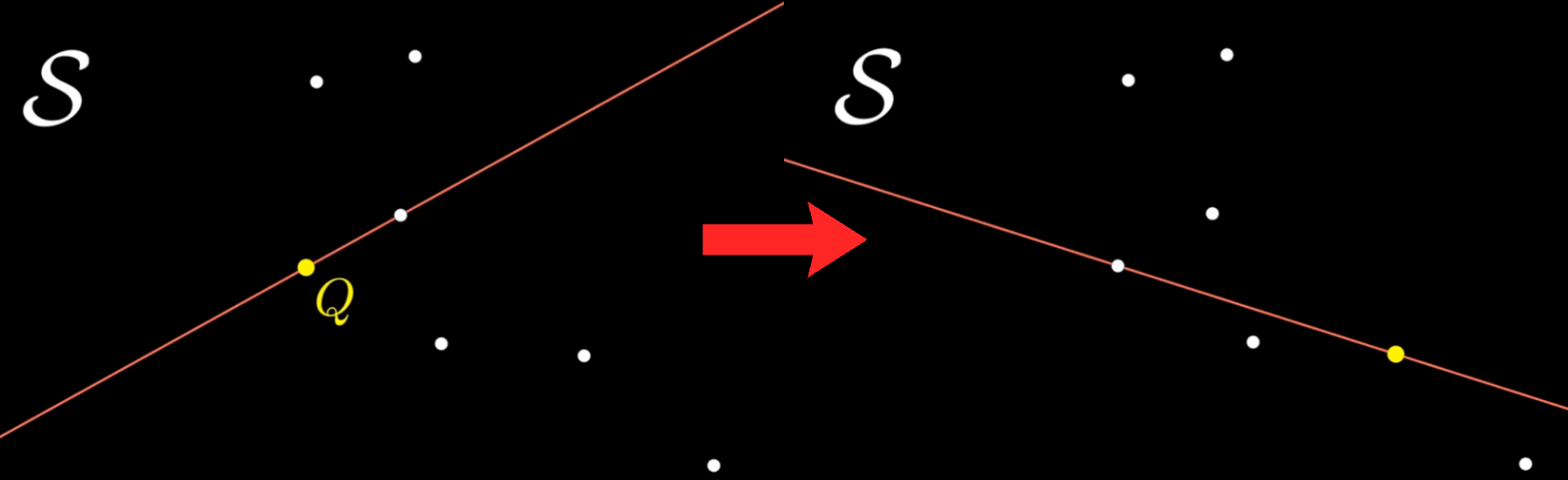

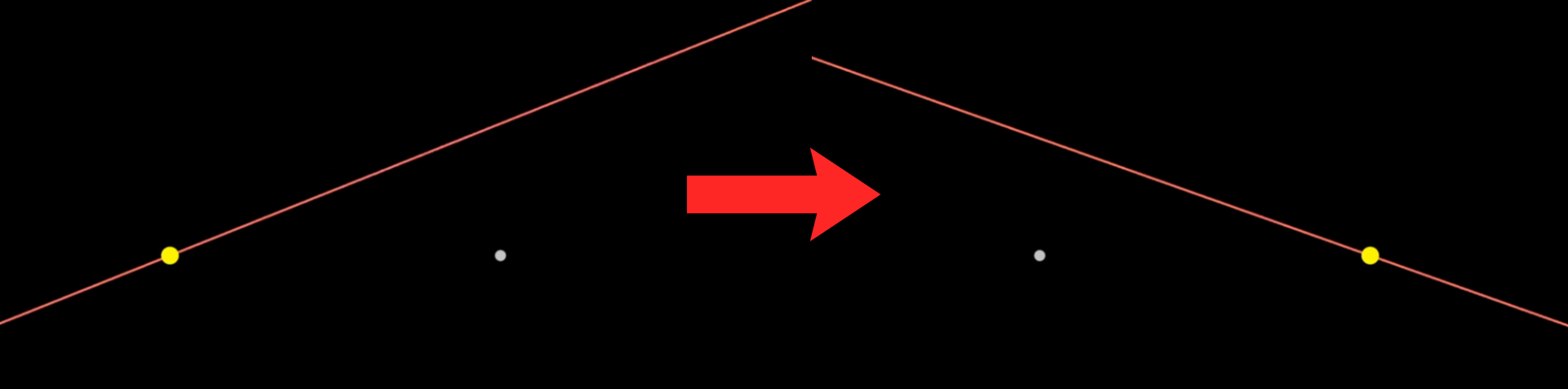

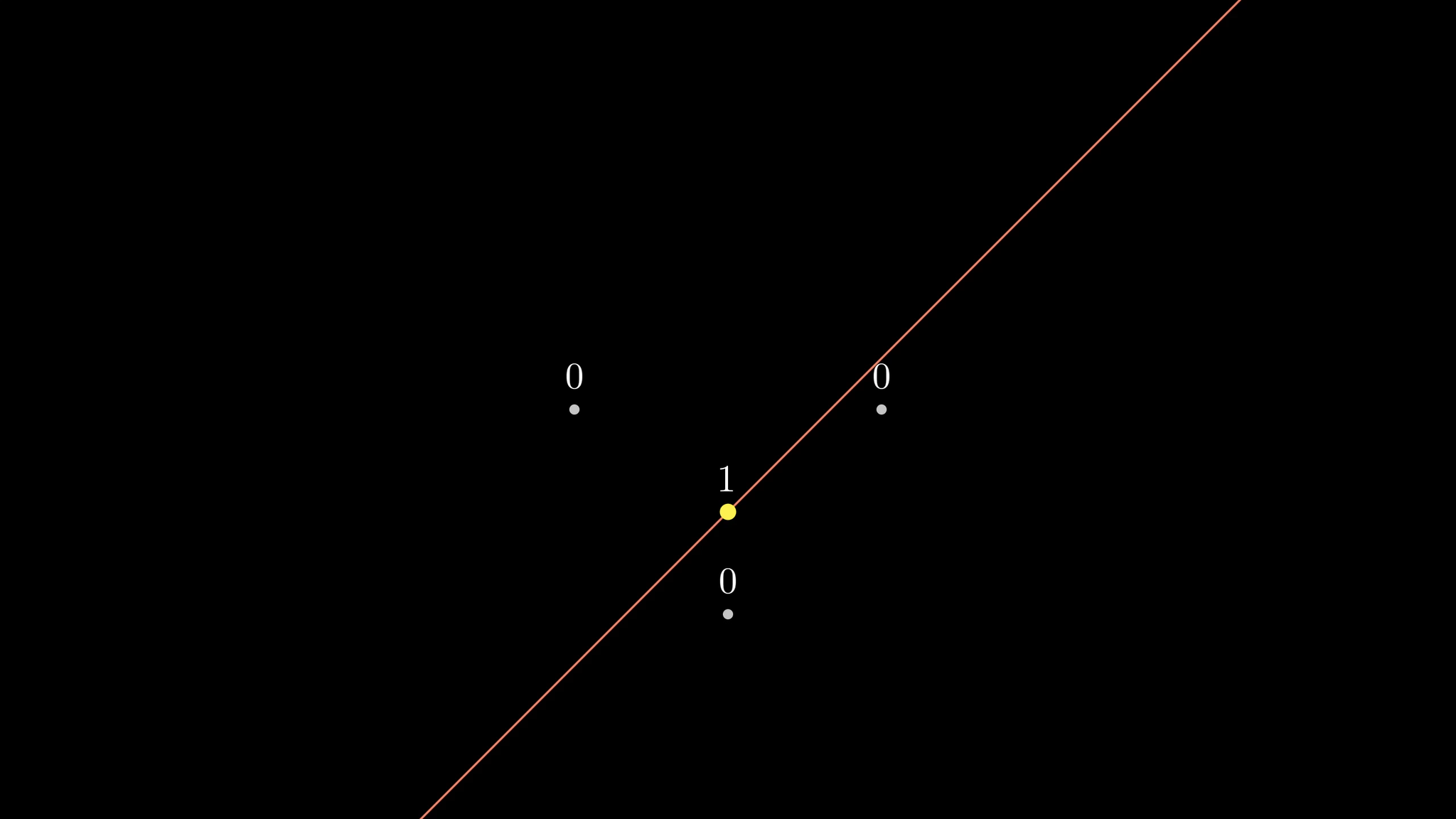

A windmill is a process that starts with a line going through a single point in . The line rotates clockwise about the pivot until the first time that the line meets some other point belonging to .

Again, while reading it’s helpful to draw out an example, so we’ve got this line pivoting around some point until it hits another.

This point, , takes over as the new pivot, and the line now rotates clockwise about , until it next meets a point of . This process continues indefinitely.

Alright, that’s kind of fun. We keep rotating and changing the pivot. You can see why they call it a windmill process. Okay, so what’s the question?

Why does the problem specify that no three points are colinear?

Otherwise, the windmill process would be ambiguous. If the line hits three points at once, it's not well defined which point becomes the new pivot.Show that we can choose a point in and a line going through such that the resulting windmill uses each point of as a pivot infinitely many times.

Why it’s “unusual”

Depending on your tolerance of puzzles for puzzles’ sake, you might wonder why anyone would care about such a question. There’s a very good reason: I’d argue that the act of solving this will make you better at math and other related fields, which I’ll explain once you’ve seen the solution.

But certainly on the surface this feels disconnected from other parts of math. Other Olympiad problems involve some function to analyze, or a numerical pattern to deduce; or perhaps a difficult counting setup or an elaborate geometric construction, but problem 2 is an unusually pure puzzle. In some ways, that’s its charm: proving that some initial condition will result in this windmill hitting all points infinitely many times doesn’t test if you know a particular theorem, it tests if you can find a clever perspective.

But that blade cuts both ways; without resting existing results from math, what could someone possibly study that would prepare them to solve this? In fact, this brings us to the second unusual thing about this problem: Based on the results, I’m guessing it turned out to be much harder than the contest organizers expected.

You see, typically, the three problems in each day are supposed to get progressively harder. They’re all hard, of course, but problems 1 and 4 should be doable, problems 2 and 5 should be challenging, and problems 3 and 6...well they can be brutal.

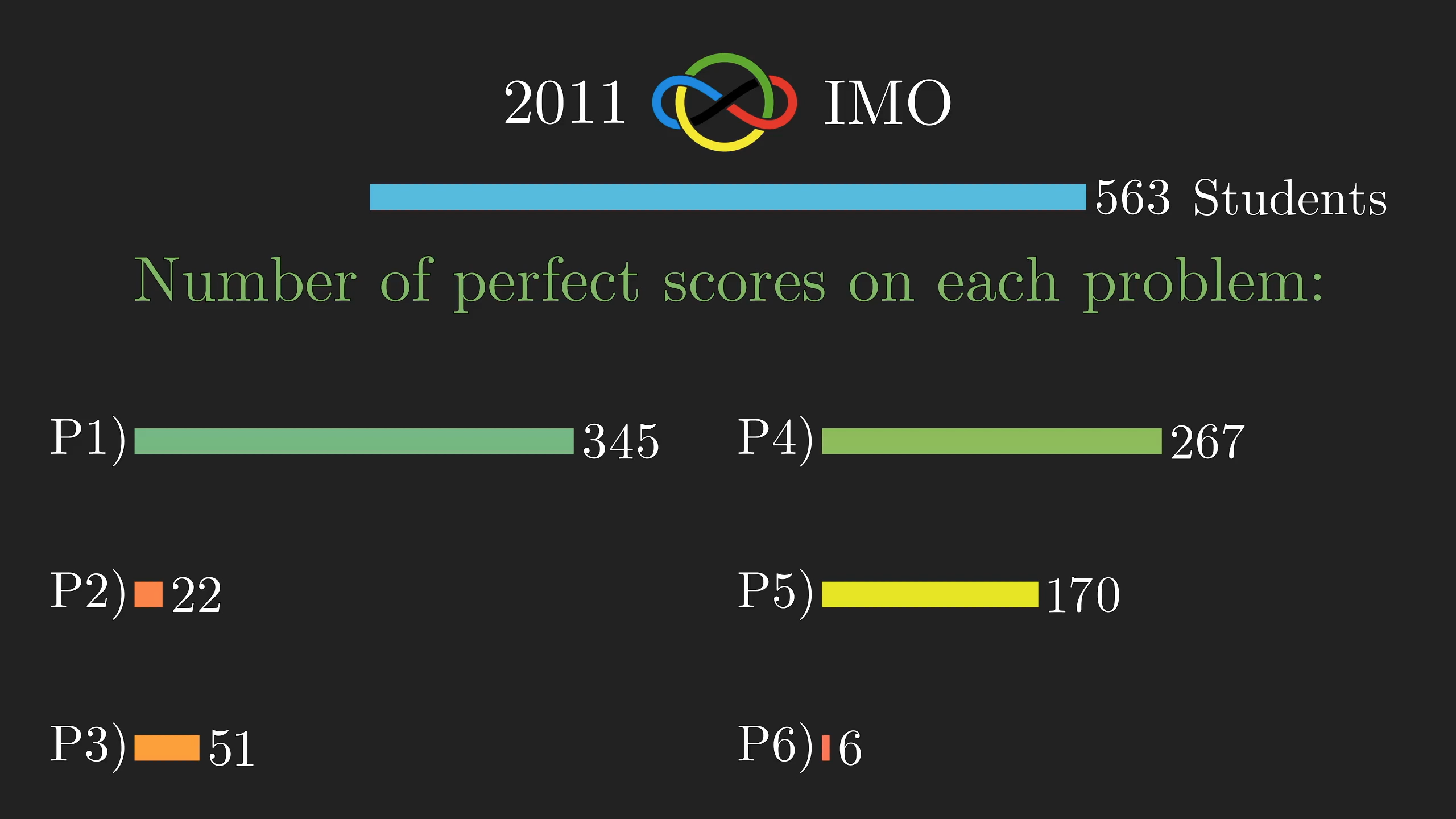

But take a look at how many of the 563 participants that year got perfect scores on each problem: Only 22 got a perfect score for this question number 2. By contrast, 170 got a perfect score on problem 5, which is supposed to be about the same difficulty, and more than twice as many, got a perfect score for problem 3, which is supposed to be harder.

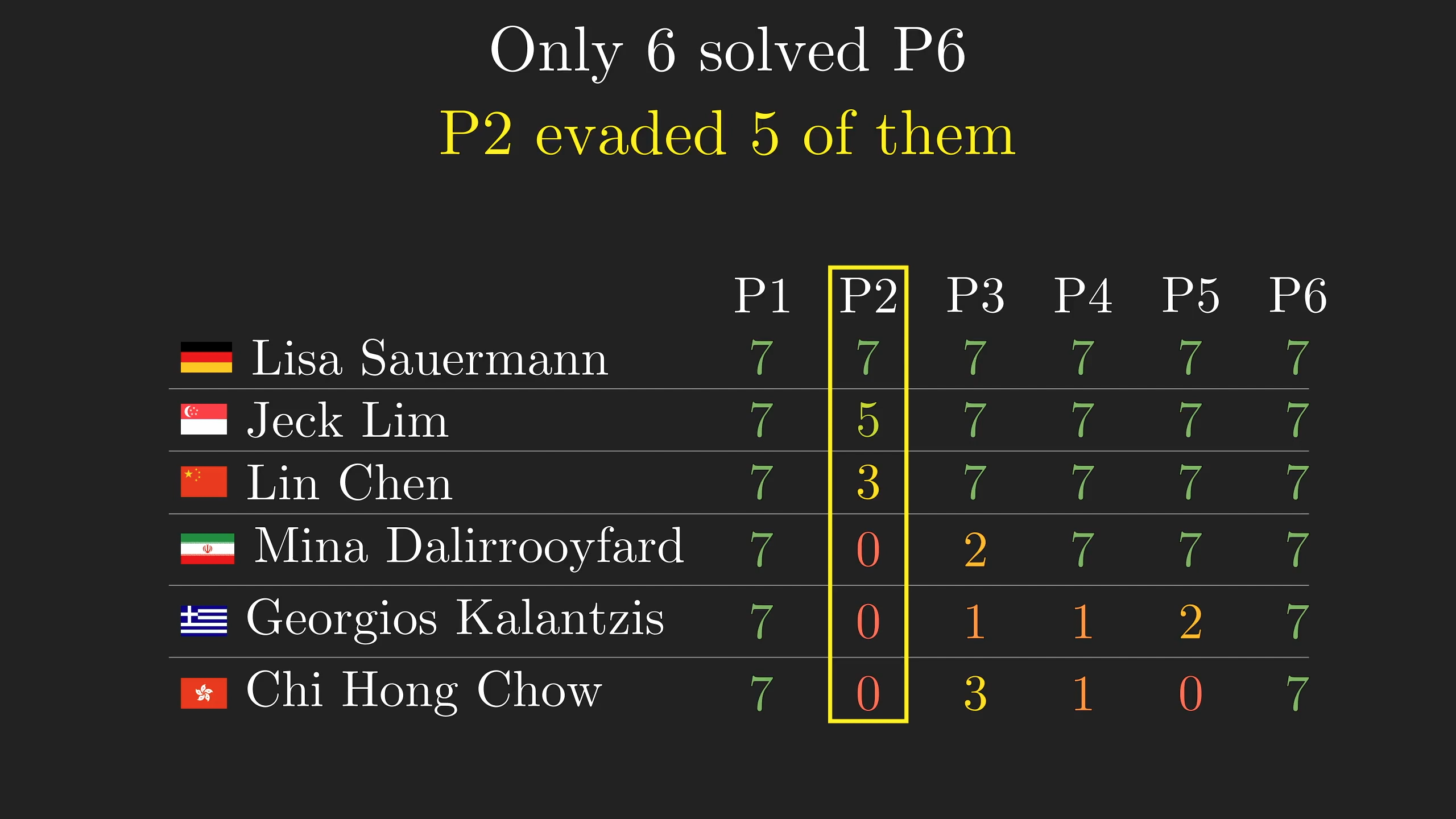

You might notice that only six students got full points for problem 6 that year, so by some measure that was the hardest problem on the test. In fact, the way I introduced things earlier was a little disingenuous, the full data would suggest problem 6 was the real clencher. But what’s strange is if you look at the results of the only six students to solve problem 6, all of whom are clearly phenomenal, world-class problem solvers, this windmill puzzle evaded five out of six of them.

Trying things out

But again, this problem isn't hard because of the background knowledge it demands, it asks only for insight. So how do you approach something like this?

The first step with any puzzle like this is simply to play around to get a feel for it, and it’s always good to start simple and slowly get more complicated from there.

The simplest case would be two points, where the line trades off between each point, so that works well enough.

Adding a third point, it’s pretty clear the line will just rotate around all of them. It might not be entirely clear how you’d phrase that as a rigorous proof yet, but right now you’re just getting a feel for things.

The fourth point is where things get interesting. In some places, your windmill will go around the four points as it did with the triangle.

However, if we put it inside that triangle, then it looks like our windmill never hits it.

Looking back at the problem, it’s asking you to show that for some starting position of the line, not any position, the process will hit all the points infinitely many times.

So for an example like this, if you start with the line going through that troublesome middle point, what happens? And again, at this point you're just playing around, perhaps moving your pencil among dots you’ve drawn on your scratch paper, questions of rigor and proof will come later.

If we begin with the configuration pictured above, what will happen?

Here you’d see that your windmill does indeed bounce off all the points as it goes through a cycle, and it ends up back where it started. The worry you might have is that in some large set of points, where some are kind of inside the others, you might be able to start off on the inside, but maybe the windmill process takes the line to the outside, where it will be blocked off from those inner points.

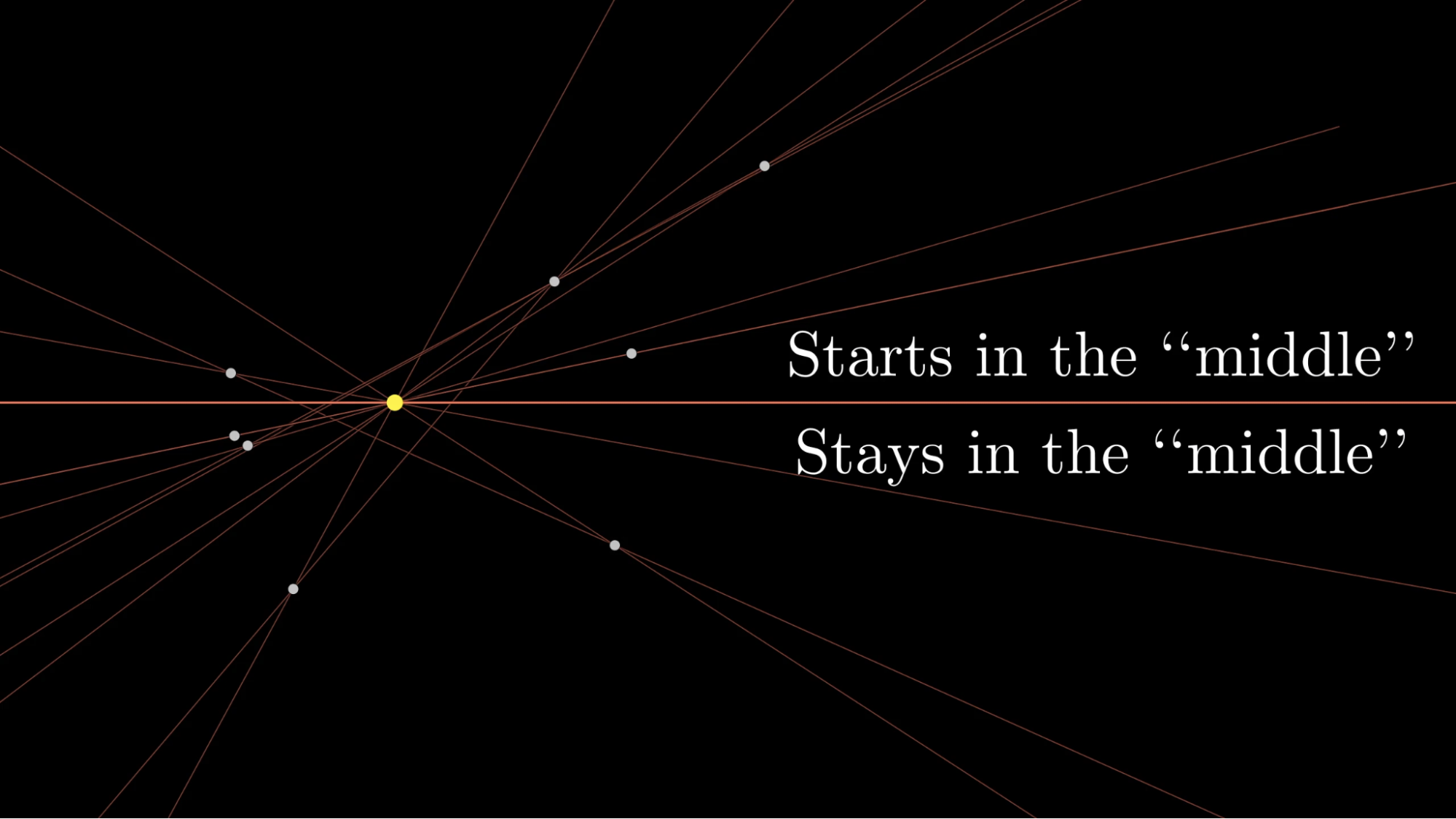

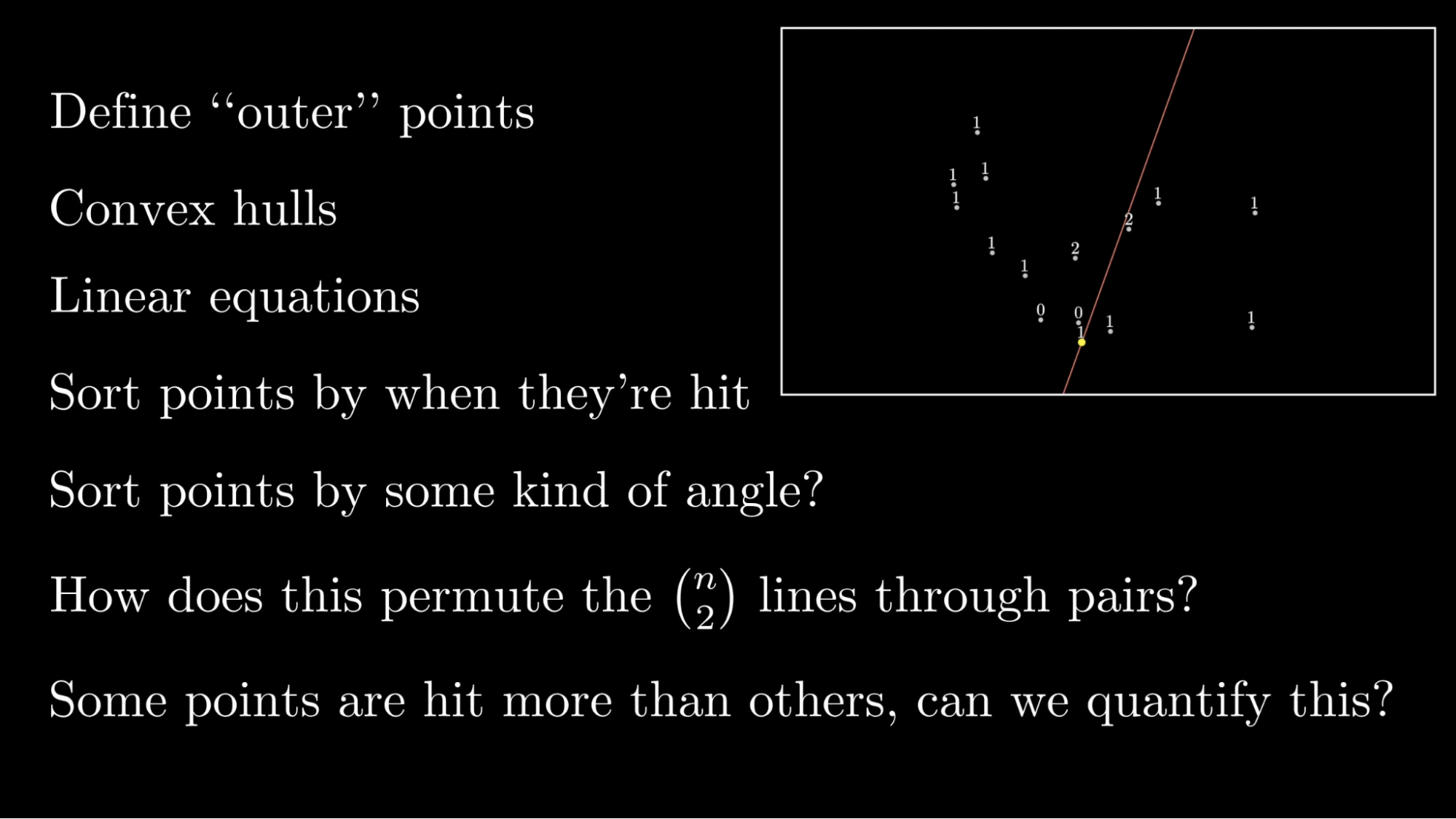

If you play around, and it might take some time to draw out many examples and think this through, you might notice that when the line starts off passing the middle of all your points, it tends to stay there; it never seems to venture off to the outside. But can you guarantee that this always happens? Or rather, can you first make this idea of starting off in the middle more rigorous, and from there, prove that all points will be hit infinitely many times?

The solution

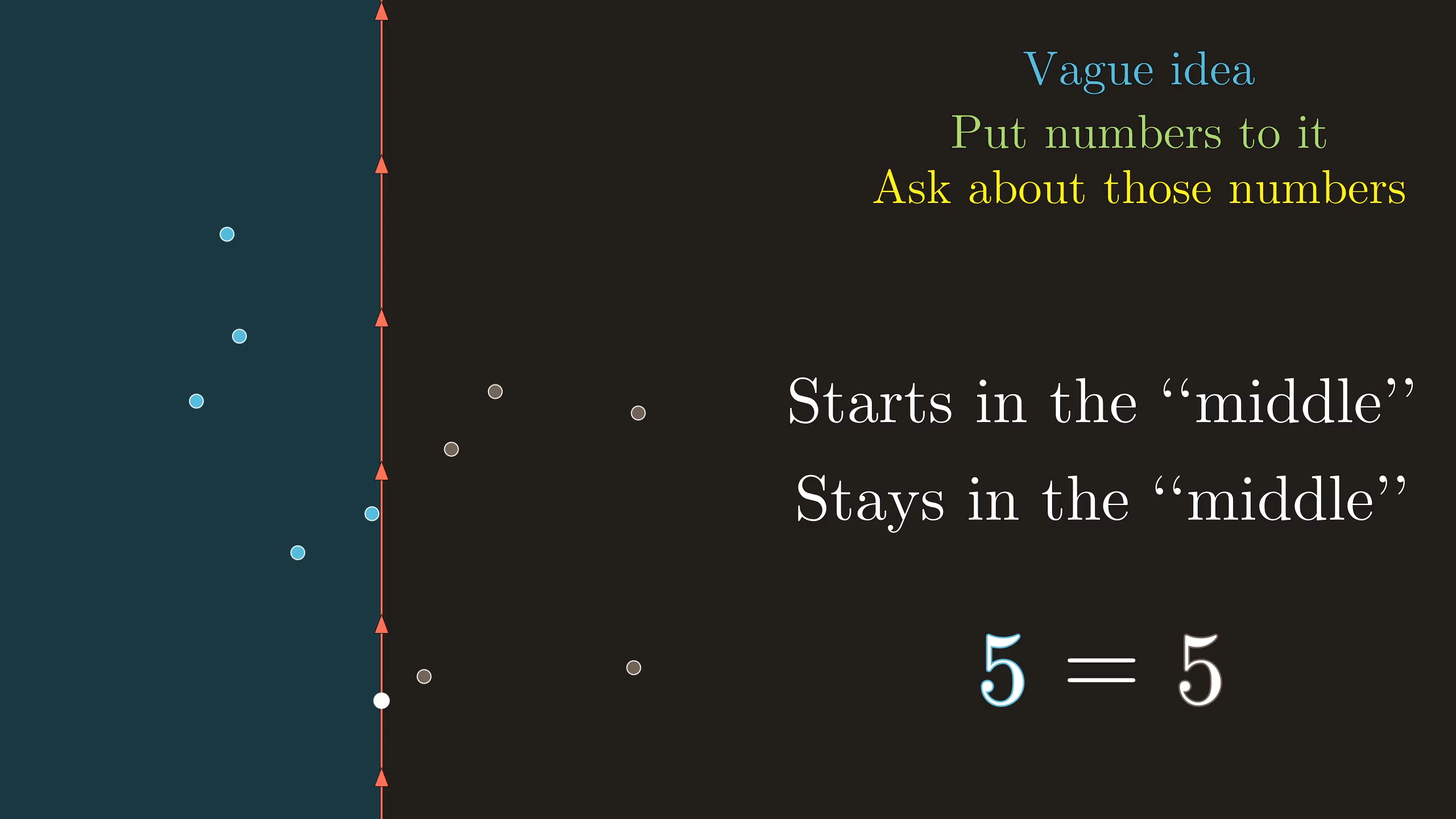

As a general problem-solving tip, whenever you have a vague idea that feels productive, find a way to be more exact about what you mean, preferably putting numbers to it, then ask questions about those numbers.

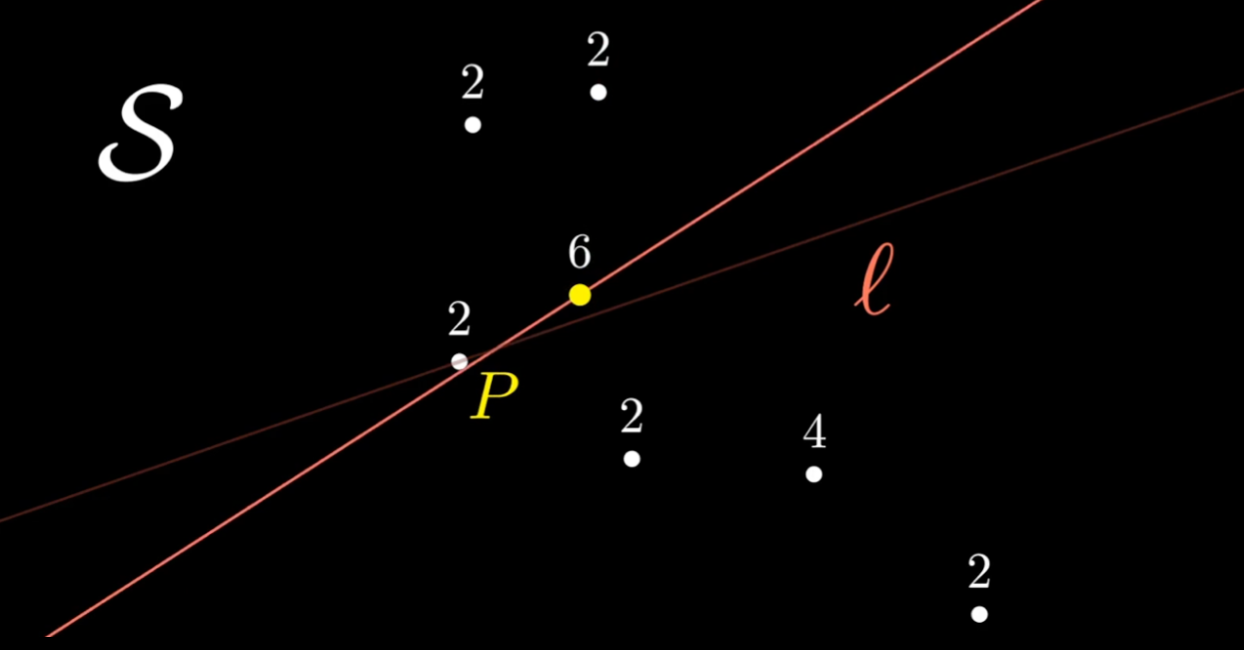

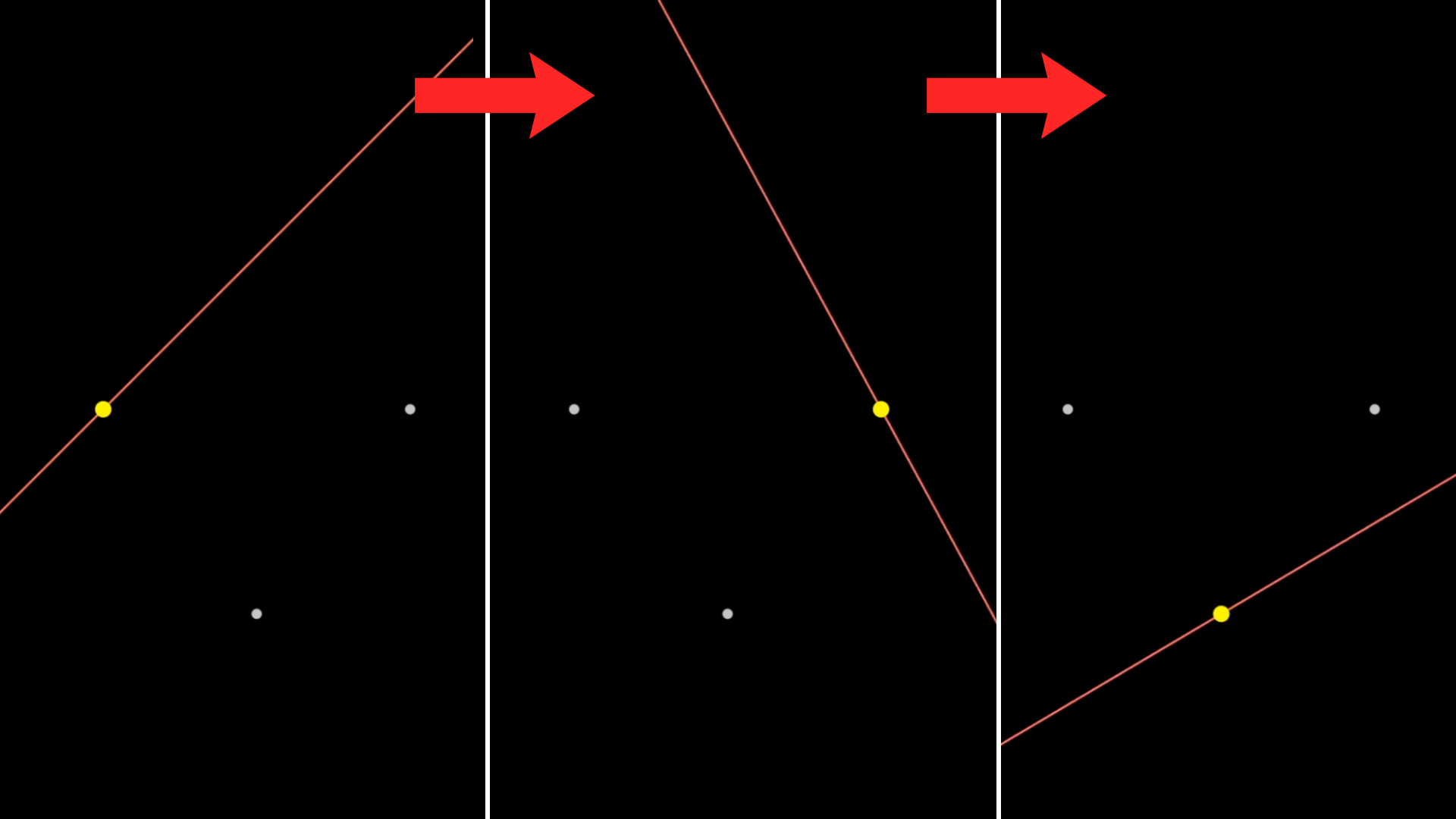

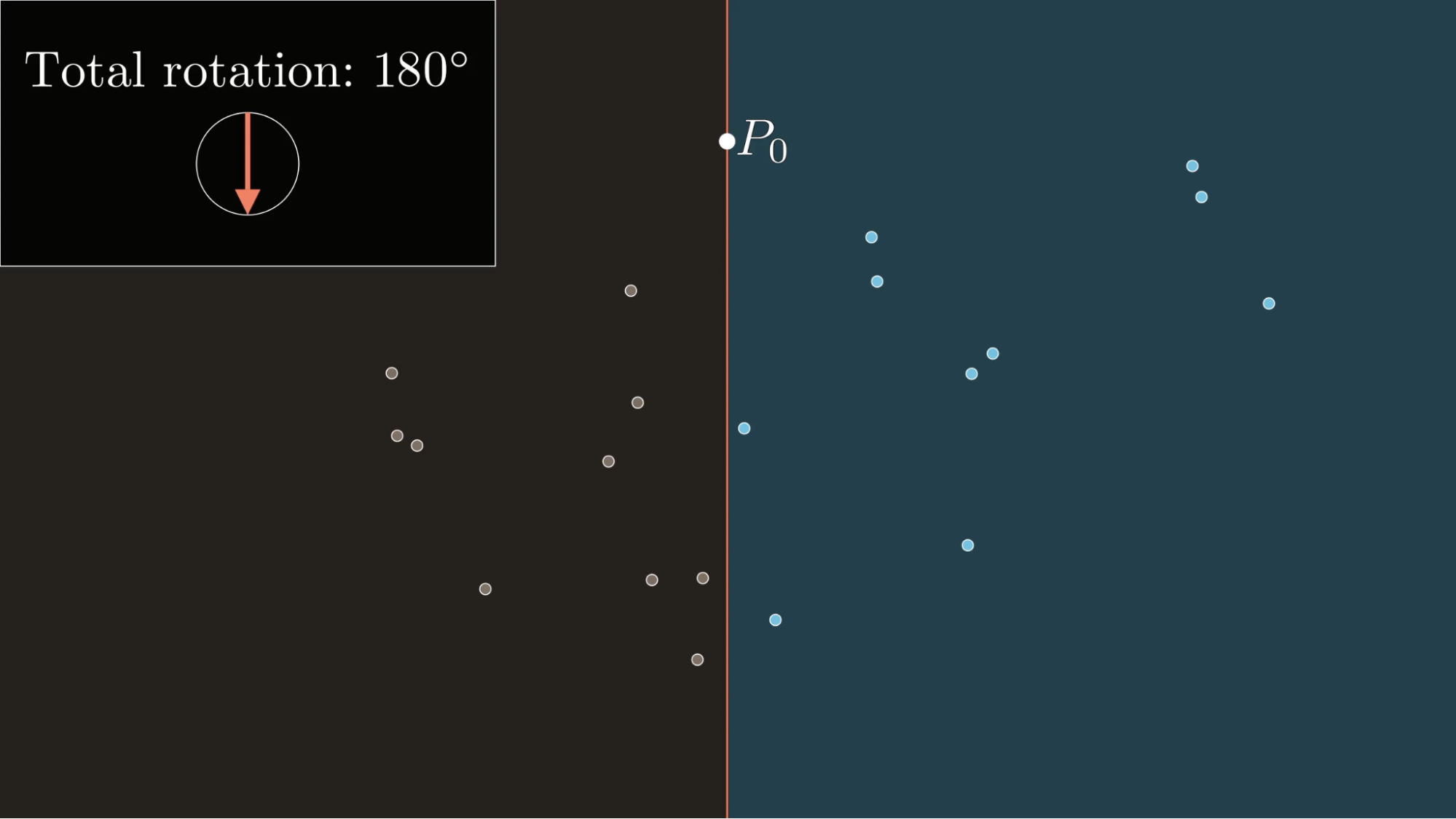

In our example, one way to formalize the idea of a “middle” is to count how many points are on either side of the line. If you give the line some orientation, you can reasonably talk about the left half, say coloring all points to the left of it blue, and the right half, coloring all points to the right of it brown, and what it means for the line to be in the middle is that there are as many blue points and brown points.

For the moment, let’s say the total number of points is odd, and the point the line passes through is colored white. So for example, if there were 11 points, then you’d have five blue ones on the left of the line, and five brown ones on the right of the line, and the one white one at the pivot. The case with an even number of points will be similar, just slightly less symmetric.

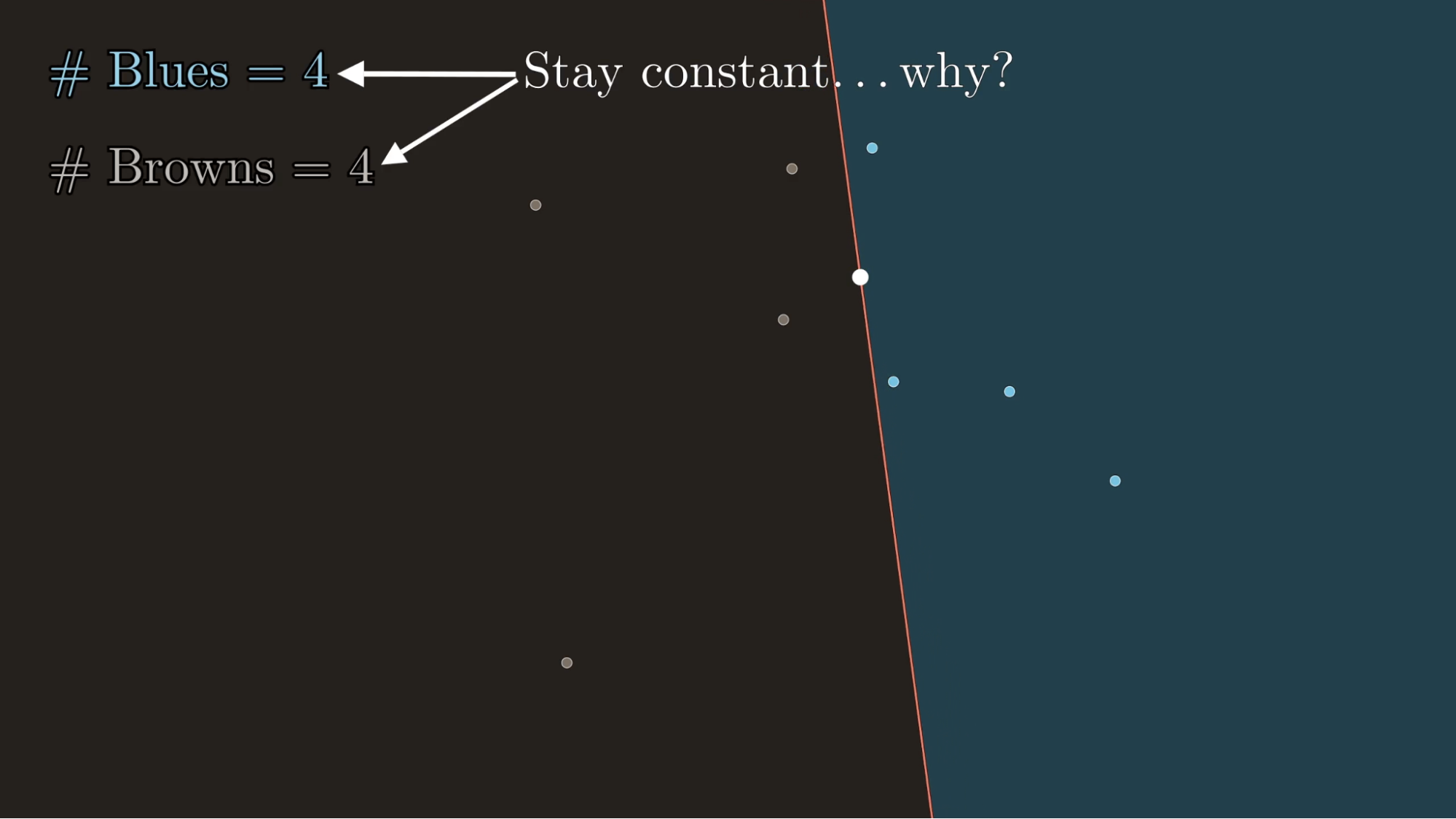

This gives you a new question to ask: What happens to the number of blue points and brown points as the process plays out? In the example shown, you might notice that it’s always 5 and 5, never changing. Playing with other examples, you’d find the same is true. Take a moment to pause and see if you can think about why that would be true.

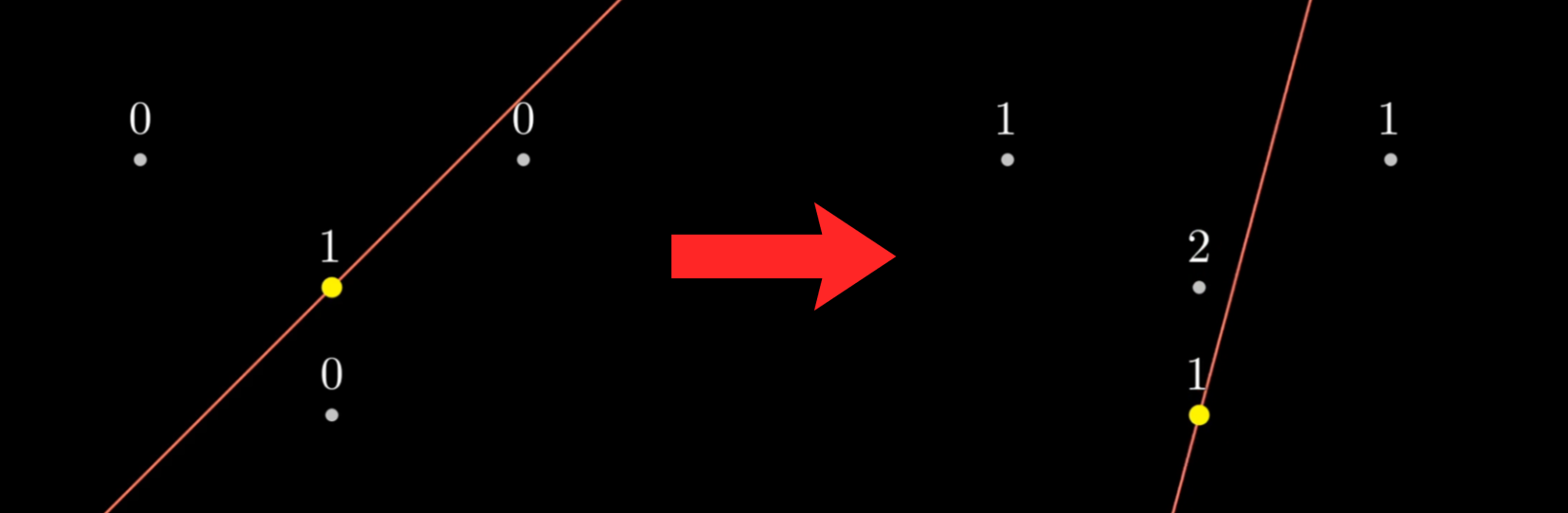

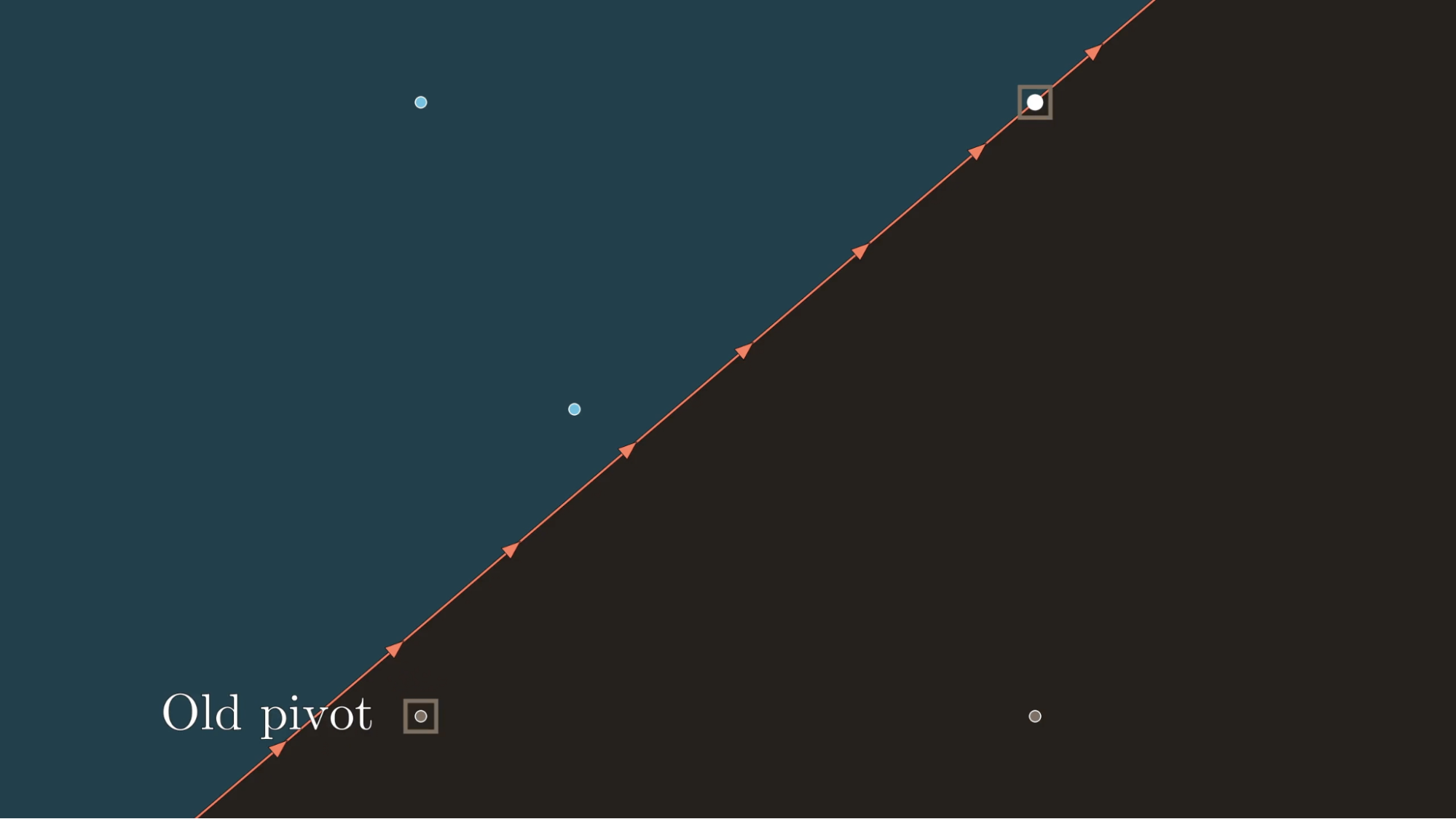

Well, the key is to think through what happens as a line changes its pivot. Having given the line an orientation, we can talk about which half of the line is “above” the pivot, and which is “below”. If the line hits a blue point to its left, it must happen below the pivot, so as it changes pivots and continues rotating clockwise, the old pivot, now above the new one, ends up to the left of the line, in the blue region. And entirely symmetrically, when it hits a brown point, it happens above the pivot, meaning that old pivot ends up in the brown region. So no matter what, the number of points on a given side of the line can’t change. When you lose a blue point, you gain a new one; when you lose a brown point, you also gain a new one.

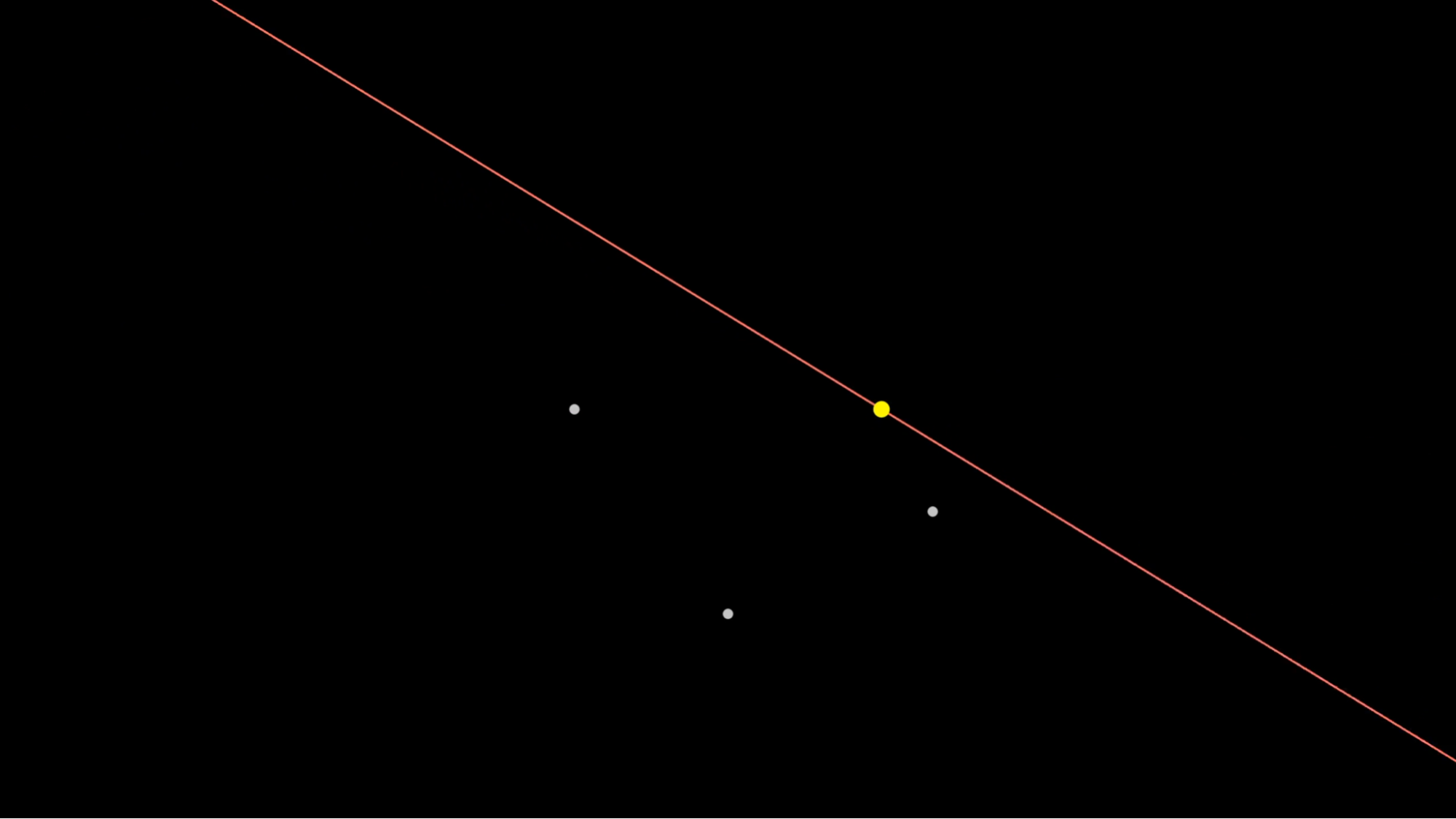

Great, that’s insight #1. Now why would this imply that the line must hit every point infinitely many times, no matter what weird set of points you dream up? Well, think about letting this process go until the line has turned . That means it’s parallel to its starting position, and because it has to remain the case that half the points are on one side, half are on the other, it must be passing through the same point it started on. Otherwise, if it ended up on some other point, it would change the number on a given side.

If the line has rotated , and ends up passing through the same point where it began, has it necessarily touched every point along the way?

So for our odd number case, that means that after a half rotation, the line is back to where it started, having hit all the other points. So as time moves forward, it repeats that exact same set of motions over and over, hitting all points infinitely many times.

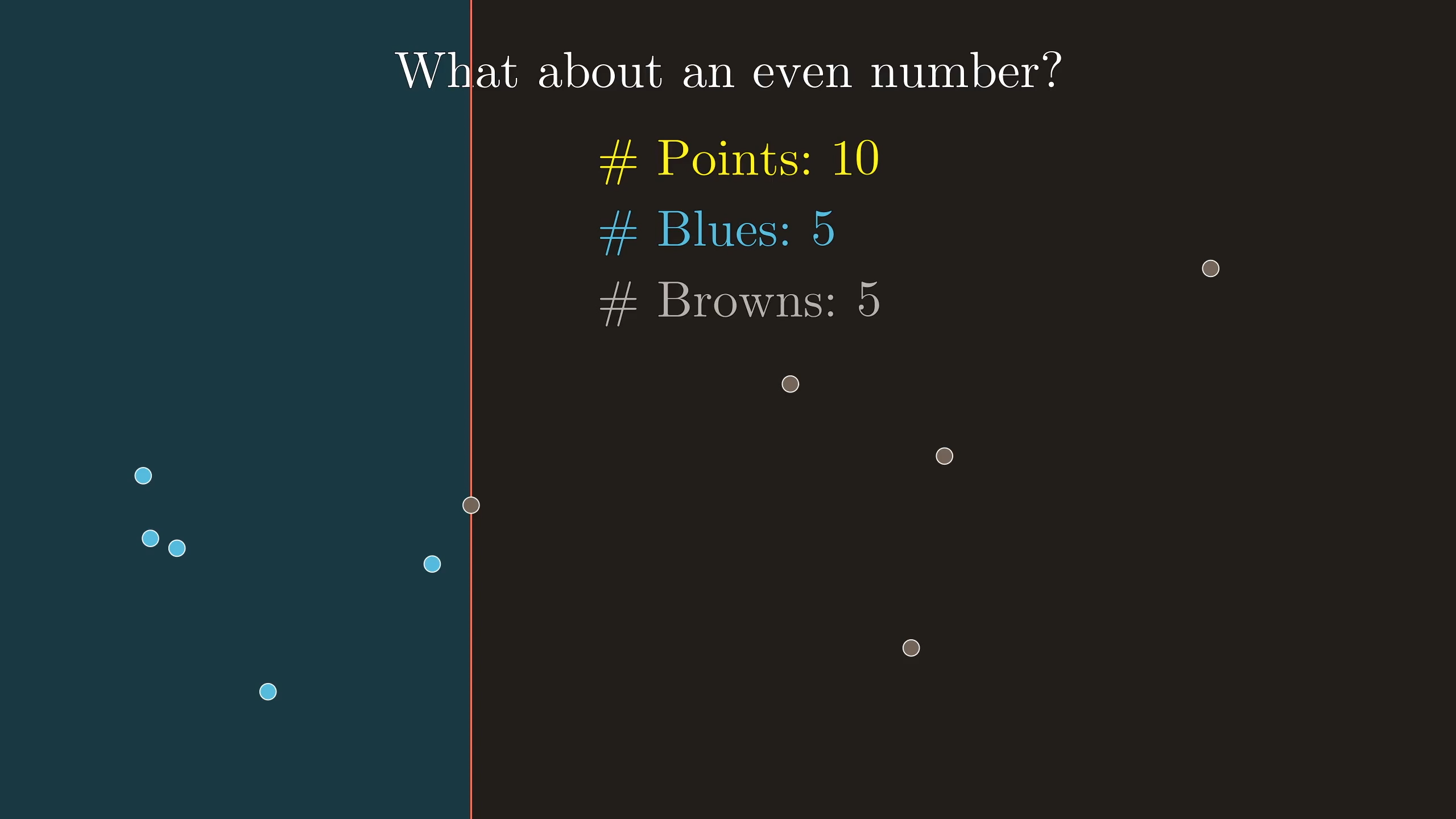

If there are an even number of points, we need to alter the scheme slightly, but only slightly. Let’s say that in that case, the pivot counts as a brown point. So we can still select an initial point so that half the points are blue, all on the left, and half are brown, now either meaning they're either on the right or the pivot.

The same argument applies that after a turn, all the points will have swapped color, although this time the line might be passing through a different point after that first half turn, specifically one that used to be blue.

Assuming there are an odd number of points, after a turn, will the line be passing through the same point it started on?

So again, you have a cycle which hits all points, and which ends in the same position where it started, so it must hit all points infinitely many times.

A few people ask "but what is the formal solution?". Take a look at this writeup, which you'll find presents an argument with the same essential idea as was presented here. It would get you full marks on the test:

The fact that an argument doesn't reference equations and sets doesn't necessarily make it incomplete. Sure, you could explicitly define what words like "left" and "right" refer to by defining such and such cross product with such and such parameterization of the line, but for most readers, it wouldn't actually remove any ambiguity. The purpose of formality is to make all the terms used unambiguous to all readers, not to dress up the language to involve sufficiently many symbols. If you understood this video, you understood the full solution.

Concluding thoughts

There are two important lessons to take away from this puzzle, the first social, the second mathematical.

Yes, it is hard

Once you know this solution and turn it around in your head a couple times, it’s very easy to fool yourself into thinking the problem is easier than it is. Of course the number of points on a given side stays constant, right? And of course when you start in the middle, every point will switch sides after a half turn, right?

But the advantage of this problem coming from the IMO is that we don’t have to rest on subjective statements, we have the data to show that this is a genuinely hard problem, in that it evades many students who are demonstrably able to solve hard problems.

In math, it’s extremely hard to empathize with what it feels like not to understand something. I was discussing this video with a former coworker of mine from Khan Academy who worked a lot on their math exercises, and he pointed out that across the wide variety of contributors he’d worked with, there was one constant. No one can tell how difficult their exercises are. Knowing when math is hard is often way harder than the math itself. This is important to keep in mind when teaching, but it’s equally important to keep in mind when being taught.

On a windmill puzzle, even if counting the number of points on one side seems obvious in hindsight, you have to ask, given the vast space of possible things to consider, why would anyone’s mind ever turn to this particular idea?

Invariants

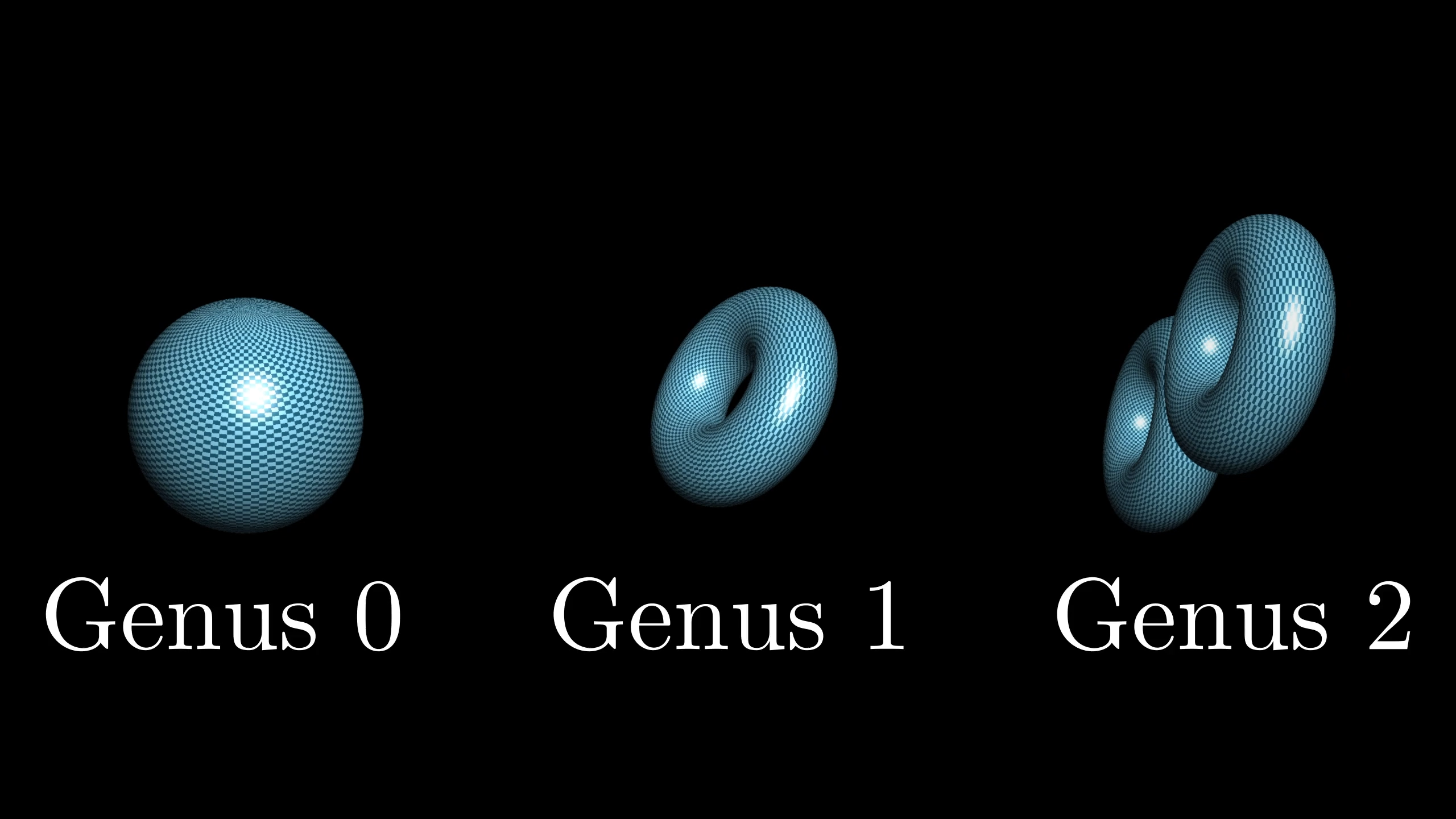

This brings us to the mathematical takeaway. What ultimately led to the solution was finding something about this complex system which stays constant during its chaotic unfolding. This is a ubiquitous theme through math and physics. We’re finding what’s called an “invariant”.

Topologists do this when they count the holes in a surface, physicists do this in defining the ideas of energy and momentum, or in special relativity when they define proper time. As a student, it’s easy to take for granted the definitions handed down to us, but the more puzzles you solve where the insight involves an invariant, the more you appreciate that each of these definitions was once a clever discovery.

Terence Tao, one of the greatest modern mathematicians and the world’s youngest IMO medalist, wrote that “Mathematical problems, or puzzles, are important to real mathematics (like solving real-life problems), just as fables, stories, and anecdotes are important to the young in understanding real life.” Sure, they’re contrived, but they carry lessons relevant to useful problems you may actually need to solve one day.

Maybe it seems silly to liken this windmill puzzle to a fairytale; a mathematical Aesop summarizing that the moral of the story is to seek quantities which stay constant. But some of you watching this will one day face a problem where finding an invariant reveals a slick solution, and you might even look like a genius for doing so. If a made up windmill prepares you for a real problem, who cares that it’s a fiction?

Thanks

Special thanks to those below for supporting the original video behind this post, and to current patrons for funding ongoing projects. If you find these lessons valuable, consider joining.